Charles Gaines’s first solo show with Hauser & Wirth, which now represents him worldwide after his departure from New York’s Paula Cooper Gallery and LA’s Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects in 2018, is another consecration in a commercial space of an artist having finally received his dues in museums in the last decade. The Hauser & Wirth show follows a joint exhibition at the Pomona College Museum of Art and the Pitzer College Galleries, “In the Shadow of Numbers: Charles Gaines: Selected Works from 1975-2012,” in 2012; a survey of his early work, “Charles Gaines: Gridwork 1974-1989,” shown at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 2014 and at Los Angeles’ Hammer Museum in 2015; and a large-scale stairwell installation at the Miami ICA in 2017. These exhibitions culminated with Gaines receiving the McDowell medal in 2019.

The works presented in the Hauser & Wirth show are brand new, all produced this year except for Manifestos 3 (2018). Unlike Gaines’s last solo gallery show on American soil — the innovative and politically provocative “Faces 1: Identity Politics” at Paula Cooper in 2018, which celebrated the historical depth of identity politics and conceptualized it as a political effort that both constitutes and transcends communities — this Hauser & Wirth blockbuster plays the hits, and does so to great success, artistically and commercially. All the works in the show are direct continuations of long-standing series. Numbers and Trees, for example, began in 1975 with the series of triptychs Walnut Tree Orchard, and Manifestos debuted at the Kent Gallery in New York in 2008. In this celebration of his formally rigorous approach to representation — the same approach that has seen his work often characterized as the missing link between the abstract conceptualists of the 1970s and the more politically minded conceptualists of today — one finds that Gaines’s program easily exceeds both these models.

© Charles Gaines, 2019

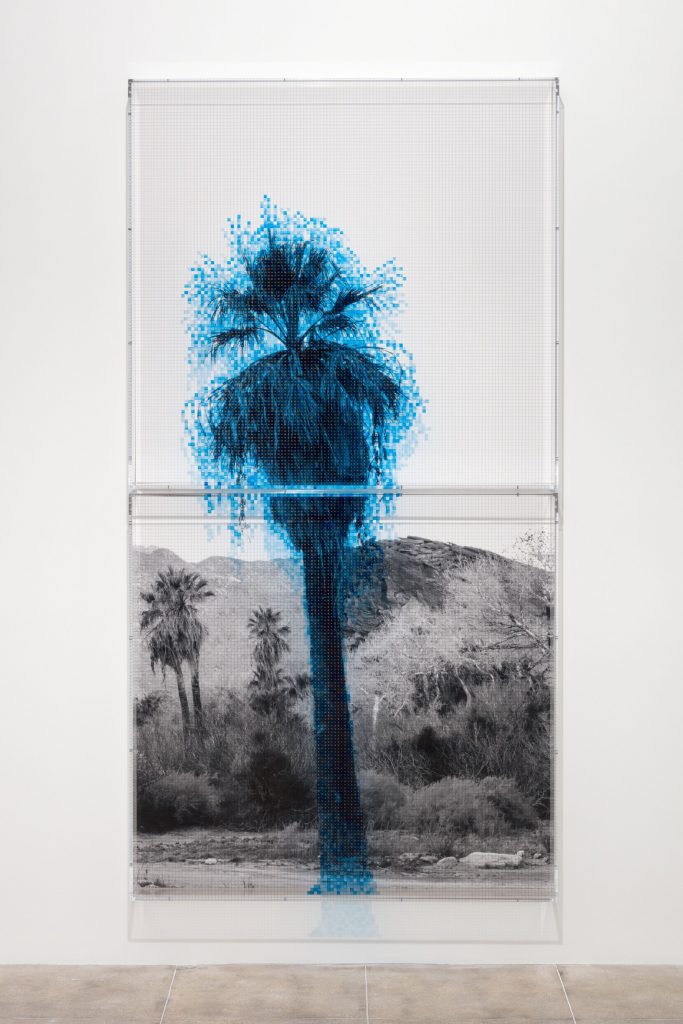

Numbers and Trees: Palm Canyon, Palm Trees Series 2, Tree #1, Cahuilla

Acrylic sheet, acrylic paint, photograph, two parts

Overall: 277.5 x 144.8 x 14.6 cm / 109 1/4 x 57 x 5 3/4 in

Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Fredrik Nilsen

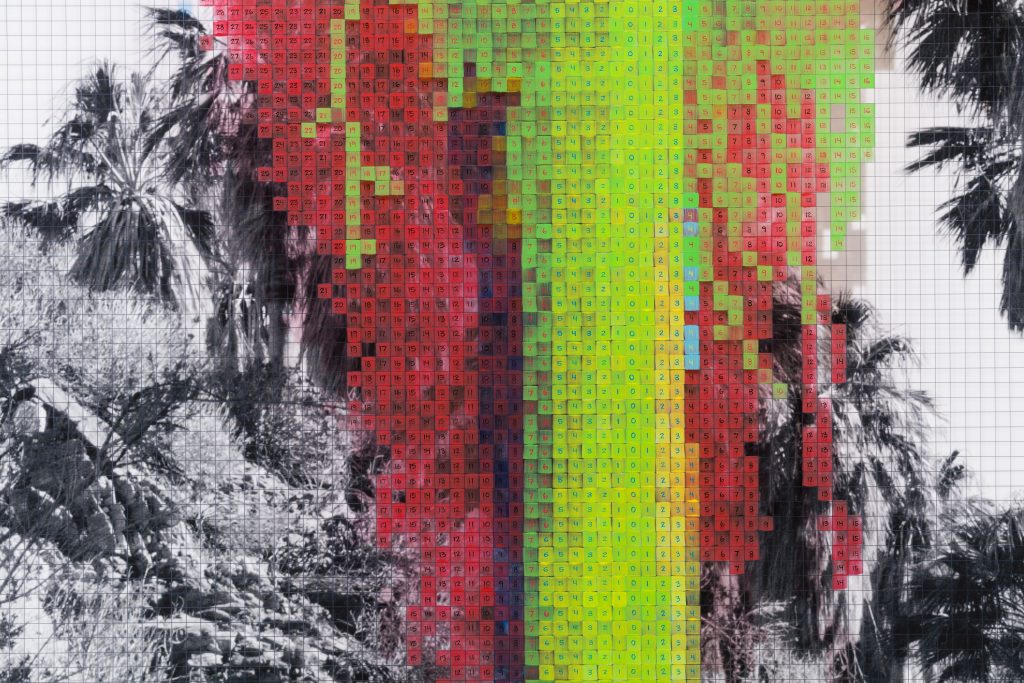

Ten new large-scale works, Numbers and Trees: Palm Canyon, Palm Trees Series 2, are characteristically at once startlingly simple and difficult to describe. Large black and white photographs, each centered on a singular palm tree native to Palm Canyon, are overlaid by two thin transparent acrylic boxes separated by a thin horizontal margin at the center. The surface of the plexiglass is gridded, each row numbered on the left, counting upwards using a combination of letters and numbers. For Numbers and Trees: Palm Canyon, Palm Trees Series 2, Tree #1, Cahuilla, each cell directly in front of the tree’s silhouette is painted blue in acrylics. Each painted cell is then filled with a small number corresponding to its horizontal position in the grid, with zero corresponding to the center axis. Each cell not mapped to the silhouette of the tree is left blank. For Numbers and Trees: Palm Canyon, Palm Trees Series 2, Tree #2, Cupeño, Numbers and Trees: Palm Canyon, Palm Trees Series 2, Tree #3, Lusieño, etc., the process is repeated with a different tree and a different color. However, each work also includes the painted cells of every work preceding it, building up layers of colors as the series progresses. This sequential accumulation finishes with Numbers and Trees: Palm Canyon, Palm Trees Series 2, Tree #10, Tübatulabal, a frozen explosion of colors all but masking the photograph underneath. In the mezzanine, four series of small watercolors un-layers this process in monochrome arrangements of miscellaneous trees.

While Gaines has applied similar processes to the human form, most notably to Trisha Brown’s dancing body, he seems to invariably cycle back to trees of all species and shapes. A generic “tree” has long been the example favored by the West European canon for explaining complex systems. The tree is Saussure’s prime example in the Course in General Linguistics to demonstrate the nature of linguistic signs (I credit this remark to writer and CalArts colleague of Gaines Leslie Dick, who also observed of Numbers and Trees: Palm Canyon, Palm Trees Series 2: “What is fabulous about them is that they are neither painting, nor photograph, nor sculpture.”). It is also Kant’s when he defines organisms as their own ends, and Schopenhauer’s when discussing the relationship between objects and ideal, between the specific tree and the general idea of a tree. Both general and just specific enough, the tree appears as the least unruly natural subject, as well as a ready-made metaphor for hierarchical organized systems, the arborescent model of roots-trunk-branches-leaves that Deleuzian rhizomatic thinking aimed to oppose. No object is better suited to presenting man-made systems as natural: in an art context, see Miguel Covarrubias’ Tree of Modern Art, which appeared on the cover of Vanity Fair in 1933, and Ad Reinhardt’s biting How to Look at Modern Art in America. Both present the cultural canon as natural growth, an industry as an organism. Similarly, in a practice as system-based and organized as Gaines’s, one might expect the trees to stand as an example of the biological origins of his systems, grounding his overall project in an imitation of nature.

© Charles Gaines, 2019

Numbers and Trees: Palm Canyon, Palm Trees Series 2, Tree #7, Mission

Acrylic sheet, acrylic paint, photograph, two parts

Overall: 277.5 x 144.8 x 14.6 cm / 109 1/4 x 57 x 5 3/4 in

Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Fredrik Nilsen

However, the artistic methods that constitute the show could not be further from nature if they tried. They do not attempt to mimic — visually or conceptually — the organizational systems of organic forms. On the contrary, they are evidently artificial, planar, and culturally specific: “In Western society, the grid is it,” Gaines explained to the Los Angeles Times. Or, as Rosalind Krauss writes: “Flattened, geometricized, ordered, [the grid] is antinatural, antimimetic, antireal.” Regardless, the three-tiered encounter between the three-dimensional tree, its photograph and the mathematical plane remains possible despite the lack of organic relationship between each of the terms. As the series progresses and the layers pile up, no ideal, no objective reality, no transcendent relationship appears. Instead, Gaines emphasizes the dissonance between the trees and the planar systems, photographical and mathematical, that render them visible. In doing so, the work dramatizes representation as a surprising encounter between forms foreign to one another.

These encounters also encompass political histories. Cahuilla, Cupeño, Lusieño, Kumeyaay, Quechuan, Chemehuevi, Mission, Fort Mojave, Kawaiisu, Tübatulabal — each iteration of Numbers and Trees: Palm Canyon, Palm Trees Series 2 is named after a Native American tribe living in what is now Southern California. After a state-sanctioned genocide and mass expropriations, Gaines finds it impossible to represent California’s desert palms without naming the oppressed populations for which they were important resources. Considering trees the quintessential apolitical object, Brecht remarked in 1939: “Ah, what an age it is/ When to speak of trees is almost a crime/ For it is a kind of silence about injustice!” As Gaines sees it, images of trees and evocations of injustices do not compete for representation, they are two ideological constructions on a collision path.

© Charles Gaines, 2019

Numbers and Trees: Palm Canyon, Palm Trees Series 2, Tree #7, Mission (Detail)

Acrylic sheet, acrylic paint, photograph, two parts

Overall: 277.5 x 144.8 x 14.6 cm / 109 1/4 x 57 x 5 3/4 in

Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Fredrik Nilsen

A similarly collisional approach characterizes Manifestos 3. Installed in a dimly lit room, the installation consists of two musical scores produced from Martin Luther King Jr.’s speech at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne (1967) and James Baldwin’s essay Princes and Powers (1957), transcribed into music by turning the letters A to H into their musical equivalents (the H stands for a B-flat). All other letters, as well as the spaces between words, are left silent. The results are recorded on the piano and played as the texts scroll on a monitor. In this dissonant encounter between the political manifesto and the musical, political ideals are considered as formal objects, composed of letters and silences just as much as of ideas and struggles. This does not void the texts of their contents — rather, formal properties act as in-between spaces within which the materiality of sound and vision can coexist with the historical realities of political demands. It is impossible to hear the generated music, slow and meditative, without letting the ideologies that created it, however blindly, permeate the room.

The complexity of this critical formalism cannot excuse the delay with which artistic and critical institutions have taken stock of Gaines practice. Due in part to his existence as a black artist who has unapologetically refused to separate his identity as an artist and his social experience as a black person in America, his contribution to the history of conceptual art has long been overlooked. At last, theory is catching up, notably with Nizan Shaked’s essential The Synthetic Proposition: Conceptualism and the Political Referent in Contemporary Art. Recent advances in literary and aesthetic theory have also provided more tools through which one can interpret Gaines’s practice. In the seminal Forms, Caroline Levine details a novel approach to formalism and its political and representational implications that begs to be applied to Gaines’s work. One thinks especially of her account of the collision, as “the strange encounter between two or more forms that sometimes reroute intention and ideology.”

Not that Gaines has ever waited for anyone to speak on his behalf — the man is a framework unto himself. Through his writing, his curatorial work, and his work as an educator at the California Institute of the Arts since 1989, he has acted as a mentor for artists who have forwarded the cause of formally innovative and politically engaged art, from Mark Bradford to Lauren Halsey. With great savvy, Hauser & Wirth have recognized this as an asset, and have invited him to transform their Book & Printed Matter Lab into a classroom, where he will conduct a ten-part lecture series on critical and aesthetic theory. Deservedly, the first five sessions have already sold out.