Cheeseburger-eating horses, life-sized sex robots, serpentine casseroles, and singing ex-Satanists litter Matthew Vollmer’s sprawling new essay collection, Permanent Exhibit. Started inadvertently as a series of hastily written Facebook status updates, the project quickly spun out into a book-length collection of single-paragraph musings on everyday life in the Age of Information. Each essay follows Vollmer’s wandering mind from topic to topic, rarely pondering his obsessions — animals, video games, cycling, violence, film, his family — for more than a sentence at a time. Instead, these winding streams-of-consciousness read more like collages, meditations on a scattered world.

While this brand of meditation might seem disastrously unfocused to the yogis among us, the disaster for readers is a delicious one — Vollmer leaps from thought to thought in an associative mode which is at once intimate and goofy, juxtaposing the warm and familiar against the inconceivably catastrophic. The result is a poignant, rapturous collection that speaks to a new generation of internet addicts — a group for whom attention is wandering and complex, as frustrating as it is beautiful.

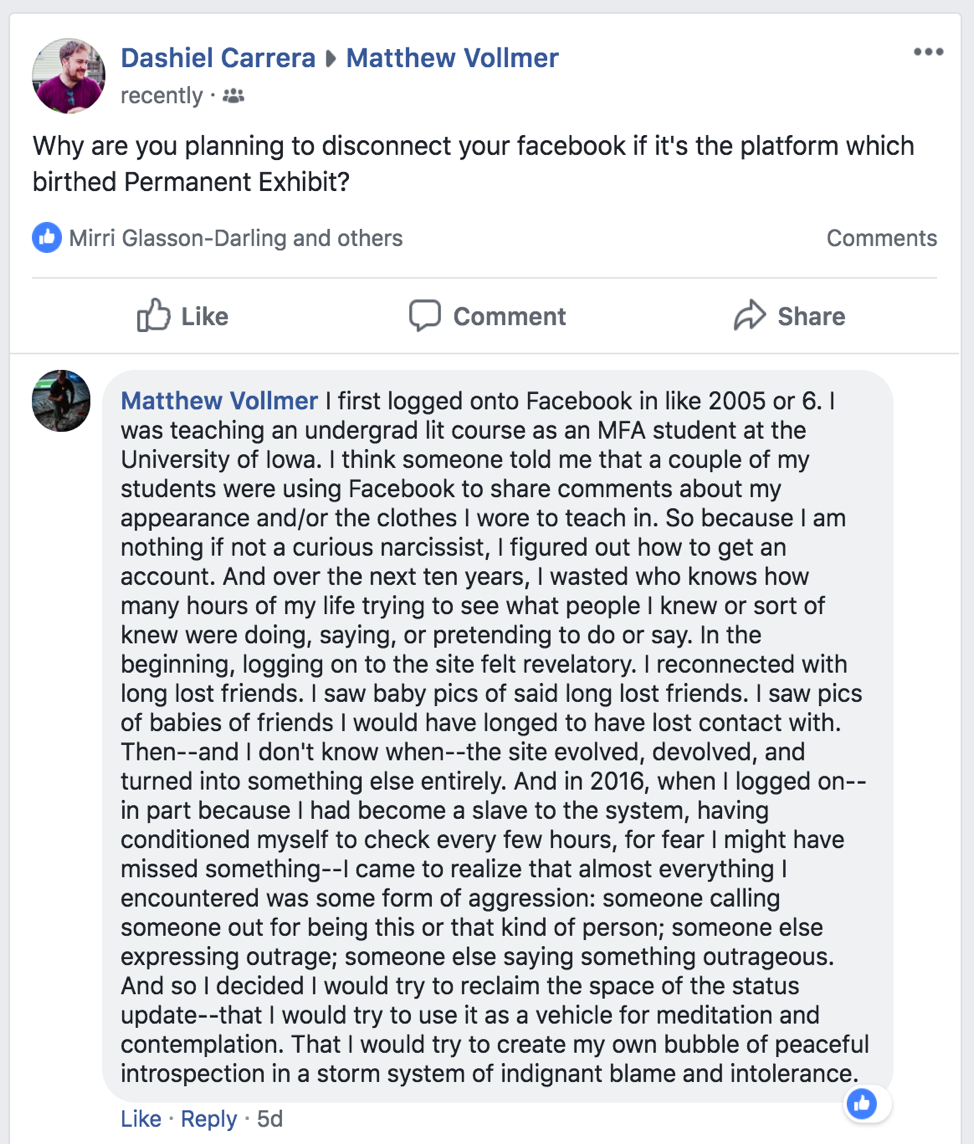

Vollmer deactivated his Facebook shortly after publishing Permanent Exhibit (I suspect to avoid an onslaught of inflammatory status updates about the midterm elections), but in an effort to return to the medium which birthed the project, I convinced him to reactivate for one last interview. Perhaps unsurprising, our conversation was as manifold and kinetic as the collection, laden with likes and comments from appreciative but confused Facebook friends who had no idea we were conducting an interview.

¤

DASHIEL CARRERA: I like the way you phrased that, a “bubble of peaceful introspection.” It sounds almost monastic. Do you see Permanent Exhibit as spiritual, in a way? Or connecting to your Fundamentalist Christian upbringing?

MATTHEW VOLLMER: I was just having this conversation with a good friend of mine yesterday about how I look back on the period during which I wrote the book as a deeply spiritual time. By spiritual, I suppose I mean that I felt tuned into the universe, dialed into a channel that allowed me to observe more carefully than usual. Because I was so often working on one of these essays, and because the work of writing them caused me to be present in the world, I felt more awake, more alert. Everything around me seemed to vibrate with potentiality and meaning and significance. To acknowledge one’s place in the world, however small, can be extremely validating. I think that’s what the writing of these essays, each one of which represents a kind of journey, an excursion, into a state of mind — or perhaps it’s merely a disposition — that looks around in wonder noting the strangeness of a world in which a horse named Patches rides in a convertible and eats cheeseburgers, or that the daughter of the founder of the Church of Satan cuts an album and titles it Bring Me the Head of Geraldo Rivera, or that there’s a chipmunk living in the base of my basketball goal, or that the sound designer of the scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark where Indy falls into the snake pit slid his hands into a cheese casserole to evoke the sounds of slithering vipers. Each time I sat down to begin one of these essays, I felt like I was reaching into the universe, into the day itself, and asking what it had to bring me. I often referred to it as “letting the day in.” I don’t know how much it has to do with my religious background, but I’m sure there’s something there. I certainly prayed a lot as a child, and I agree with Simone Weil when she says, “Attention, taken to its highest degree, is the same thing as prayer. It presupposes faith and love.” So with that in mind, Permanent Exhibit does — in many ways, at least to me — feel something like a prayer book.

The first piece in the collection, “Status Update,” which you wrote off the cuff to launch the project, seems entirely collage and free-associative. This spirit carries into the other pieces, but there’s a clear change — they become more methodical, providing evidence and elaboration when needed.

How did this book evolve from the form of status updates to the form of a book?

I wrote the first piece by accident. No, wait. I guess I should say that I wrote it mindlessly. It was a knee-jerk reaction to whatever was happening on July 6, 2016 and what the people on my feed were saying about it. I had outrage fatigue. So I wrote a status update about riding my bike, seeing a fawn nursing from a deer in the middle of the road, running the dishwasher, eating a slice of pizza big enough to wrap around my face. People responded. The post got a lot of likes. I thought, huh. So I wrote another one. And another. And another. The more comfortable I became with the associative mode, the more I began to let myself linger on certain subjects, or the more focused the string of associations became. After a month of writing, I felt as if I could string them all into a manuscript, assuming I kept writing, which I did. Looking back at it now, it feels like the book sort of wrote itself.

You mentioned before that in 2016, everything you saw on Facebook was some form of aggression. It took me a few essays to realize, but for a book that’s so funny and playful, there’s a real violent undertone. You’ve got the algae that smell like dead animals in “Can’t Feel My Face,” your fear of crashing on your bike and bleeding out on the side of the road in “33rd Balloon,” your father cutting off the head of a snake in “Well of Souls,” mass vehicular homicide while playing Grand Theft Auto V in “Out of Lives,” and so on…

Yet this violence passes by with little meditation. In the essay “Robocall,” you go straight from five police officers being killed by a sniper to an article on sex robots.

How do you think about violence? How have social media and video games shaped your understanding of violence?

Good question. I think like everyone else, I think I’m kind of numb to violence — that is, until it’s close enough that it causes pain. Simulated violence — participating in games or pretending to kill or be killed — has always had an allure, and maybe it’s because in these games the person who dies always ends up cheating death. If I’m shot in a video game, or I leap from a skyscraper, or throw myself in front of a bus, or fail to deploy my parachute when jumping out of an airplane, or walking into someone’s beach campfire and self-immolate, I always come back to life. I think that’s the thing about these games I love — the fact that we never really die.

As for social media — we’re inundated with news about violence. How many mornings since the shootings here at Virginia Tech have I woken up to read news about a mass shooting? I lost count years ago. I always think about that Onion headline: “‘No Way To Prevent This,’ Says Only Nation Where This Regularly Happens.” But now, even the word “regularly” seems outdated. It feels like it’s happening all the time. Maybe that’s why I simply mention the deaths of shooting victims. I want to acknowledge them, but also I have to go on with my day. And I can’t think about sad things all the time, which is now what social media wants me to do.

One of the most poignant moments in this book is the description at the end of “33rd Balloon” in which one final balloon is released to honor the death of the Virginia Tech shooter, because “he had once been a baby, a boy, a son, a brother…”

Has the shooting shaped how you write or think about the world?

Very much so. I imagine getting shot a lot more than I used to. It’s just part of the way I go about the world. But I also often think about the aftermath of the shooting: the news media tents, the students wandering aimlessly about campus, taking naps on the floor of the Blockbuster, reading all the signatures on the giant cardboard placards where people wrote messages to the fallen, the ribbons tied randomly to trees, the groups of evangelists walking around campus, asking people if they died today would they see the face of Jesus. It was so bizarre; we had department meetings where grief counselors told us that we should find things to do with our hands. My wife walked around campus soon after the shootings had happened and ended up in a room at the University Inn where it was apparent that family members of the slain were being addressed for some reason. The person speaking said that if they were being interviewed on TV, they could prevent themselves from crying if they wiggled their fingers and toes. The weeks and months following the shootings were filled with deep sadness and utter absurdity. I couldn’t walk on campus for years afterwards without thinking about them. And, of course, I still do.

That seems a perfect example of the kind of absurd associative leap the book thrives on: one day, mass murder; the next, toe wiggling. It’s funny to think that these juxtapositions aren’t just constructed — they are a part of our daily lives.

You wrote recently that you see your life as a collage, and a striking feature of the book is the way in which moments of poignancy — I’m thinking of your fear of your son’s death, or of your desire to tell your wife she looks more beautiful everyday — are absorbed by the quotidian or the Internet tidbit.

Do you see the quotidian, the distressing news stories, the fun fact, as equal parts of your new writerly conscience? How do you negotiate their correspondence?

I don’t know that it’s “new,” necessarily. And I don’t think that we need the internet or social media in order to see “life” as a kind of collage. I imagine that experience for humans has always been a kind of montage; we’re constantly experiencing, selecting and discarding information, and using that information to make up stories about ourselves. As for how it all balances out, or whether the quotidian or distressing or “fun” become equals — I have no idea. Then again, maybe they do. At the very least, they live side by side, don’t they? Those parents who traveled to Virginia Tech after their babies were slaughtered had to live for a time in one of our local hotels. They woke up and fed themselves from a carb-laden breakfast trough, checked their emails to find condolences sitting alongside bill payment confirmations and party invites, and failed to comprehend a world where the loves of their lives could no longer be found. The knowable and unknowable are eternally entwined in every moment; sometimes we are awake enough to acknowledge this and sometimes we aren’t.

Do you think this project could have come into being offline? At the end of the essay “Out of Lives” you talk about playing Ms. Pacman in a “delightfully panicked state,” which often describes how I feel using technology. In what ways do you find the internet, tech, and games invigorating?

I really don’t think I would’ve written the book without the internet. It’s funny you ask what I find invigorating about playing video games. I’ve spent a lot of my free time recently playing Red Dead Redemption 2, luxuriating in its resplendent facsimiles: shadows of trees shifting, the way light glistens on mud patterns, deer and squirrels and bighorn sheep bounding away in front of the horse I’m riding, the way my character’s hat gets blown off my head during a shootout. It’s an exquisitely beautiful game, and part of the joy — for me, anyway — is that I walk away from it and enter the “real” world and am suddenly awake to its particular features. Like so many forms of successful storytelling, it invites the player into an immersive world, one that is richly complicated and emotionally compelling.

I read that this book was born in part out of frustration with writing your memoir. Ironically, the collection contains quite a few memories from your childhood, and operates in an associative mode often linked with memory.

Has this project changed how you think about memory? Has it affected the process of writing your memoir? What can we expect from the next Matthew Vollmer project?

Yes, that’s true. I was working on a longer book that will attempt to tell the story of what it was like to grow up in the mountains of western North Carolina, in a Christian denomination that preached a lot about the end of the world. It’s about memory — how it serves and fails us. It’s about growing up and growing older and what it means to say goodbye to a set of beliefs and rituals that so many of your loved ones continue to embrace. It’s about mountains, wilderness, serpents, demons, and angels. I don’t want to say much more than that, except it sort of operates in that associative mode you just mentioned, only on a much grander scale. I hope I can make it work.