The following article is the first in a five-part series about the movement at the Standing Rock Indian Reservation. The mobilization, of people and resources, which was spurred on by the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline, began an unprecedented convergence of hundreds of Indigenous Tribes, and thousands upon thousands of people. The series, which was originally written as a single piece, offers the reflections of Brendan Clarke, who traveled to Standing Rock from November 19th through December 9th to join in the protection of water, sacred sites, and Indigenous sovereignty. As part of this journey, which was supported by and taken on behalf of many members of his community, Brendan served in many different roles at the camps, ranging from direct action to cleaning dishes and constructing insulated floors. He, along with the small group he traveled with, also created a long-term response fund, which they are currently stewarding. These stories are part of his give-away, his lessons learned, and his gratitude, for his time on the ground.

A grandfather says to his grandson,

“Inside each of us are two wolves.

They are constantly fighting one another.

One of them is the wolf of kindness, bravery, and love. The other is the wolf of greed, hatred, and fear.”

The grandson stops and thinks about it for a second. He then looks up at his grandfather and says, “Grandfather, which one wins?”

The grandfather replies,

“Whichever one you feed.”

–Cherokee Legend, The Two Wolves

SETTING THE CONTEXT

A student from the high school where I worked this past fall asked me a very simple and poignant question upon my return from Standing Rock: Why did I go?

I could answer by telling him that I went because I have a commitment to the water, and when I asked, the water said, “Go.” I could tell him how I was exploring the theme of courage with my 9th grade English class, while reading To Kill A Mockingbird, and could no longer teach about courage, without finding the courage in myself to stand up against injustice, here, now. I could tell him how, as I had learned about the Civil Rights Movement, abolition, or any other movement of similar scale in this country, that if I had been alive during those times, I always hoped that I would have taken a stand, and risked my life for justice. I could tell him how with Standing Rock, it dawned on me that these are such times, and I am alive. Or I could simply tell him that I responded to the call for help from Indigenous leaders at the Bioneers Conference. All of this would be true, but the truth goes even deeper.

In the summer of 1847, 700 Dutch colonists arrived in the territory that settlers had declared the state of Iowa just one year prior. These pilgrims left behind soldiers and local authorities in Holland, who had targeted them based on their religion. Central to their outlawed beliefs was a belief in the separation of church and state, and the freedom to chose their religion. As a means of oppression, the Dutch government attacked their right to assembly, declaring any group of more than 19 practitioners a “mob,” and ordering them to disperse. Resistance grew alongside the oppression; sermons and meetings were held in barns, kitchens, and anywhere else that people could find. In at least one instance, as soldiers broke up a religious sermon, the crowd sang psalms to quell the chaos. Their faith and their psalms were their main defense against persecution, and at times, their singing was so fervent, that the humbled authorities were the ones to disperse. Nevertheless, those suffering under persecution eventually decided to leave. They headed west to North America. Most arrived in Pella, Iowa, and became known as the Pella Pilgrims. Among these Dutch pilgrims were my great-great-grandparents, Klazina van der Linden and Dirk Gleysteen. My ancestors ventured even farther west than many in their community and landed in Sioux County, Iowa, 200 miles from the Missouri River, in the heart of Turtle Island.

In this short, simple story, is the rootstock of colonization, and western expansion. One can graft many specific families and cultures to this story, but the root remains the same: those who have been oppressed become the oppressors. As violence in their own land turned toward them, my ancestors fled. In their fleeing, they arrived, in a frenzy of genocide and land theft, on someone else’s home ground. As they arrived into this foreign land, which side of history did my ancestors stand on? Did they, wittingly or unwittingly, shift roles and continue the violence? What damage and heartbreak has the long line of pilgrims and refugees sown in their faithful seeking of a better life?

The root of the word pilgrim comes from the Latin word peregre, which literally means the “land beyond.” It is literally one who goes to land out of sight. However, in a religious sense, there is a different, deeper meaning. The word pilgrim indicates a traveler to a sacred place. Knowingly or not, my ancestors arrived in the sacred lands of the Indigenous Peoples already living in that place. As Dirk Gleysteen himself wrote in his memoirs, Gleysteens in America, “just across the river lay the great unexplored lands of the Dakotas, then an undivided territory and the home of the receding buffaloes and the troublesome Sioux Indians.” Of course, such a description begs the question: by whom, were these lands unexplored? And why were the buffaloes receding? And what, made the Sioux Indians so troublesome? At least one answer to all these questions is the same: European settlers. Perhaps even more haunting is the question that lurks in the lines of all this history, “What am I, as a descendent, at least in part, of European immigrants, left to do with all of this?”

Although I was born on this land, and of these waters, I am not Indigenous to this land. I am not part of the many cultures sprung from this place, as the word “indigenous” implies. I do not speak a language born of this place. I did not grow up eating plants and animals whose very nature was wrought through centuries of evolutionary balance with all else already here. I do not know the old songs of this place. In truth, neither do I know the songs and stories of the places where my ancestors come from. I am something between an orphan and a guest.

But, I was raised on this land. I went to school on this land, and though it was part of the broader system of compulsory education, my family chose it for me. This, compared with the forced assimilation through Indian boarding schools, the last of which closed in the 1990s, when I too was in elementary school, is a privilege of astounding proportions. But despite my many years of schooling, and access to higher education, I must admit that I was and remain largely ignorant of the story and history of this land, and its Indigenous Peoples. This is not simply a lack of will on my part, but also the willful, often times deceitful omission of history by those writing the story. Perhaps, worst of all, was the insinuation that Native Americans themselves were a thing of the past, exclusively a subject of history. That is to say: as a young boy, growing up at the edge of the capital of the United States of America, I firmly believed, as I had been taught, that all Native Americans were dead. Thankfully, they are not. Nevertheless, I am left to acknowledge that I have not only inherited stolen land, but also a legacy of broken treaties and broken relationships, and the corresponding opportunity to work for healing and reconciliation with and alongside the original inhabitants of this place.

THE GREAT AWAKENING

When I was in 5th grade, after years of waiting, I was allowed to join my school’s Stream Team. Mrs. Geddes, and her sidekick, my mom, had been running the program together for a few years. We were on the cutting edge of technology, learning a language called “HTML,” so that we could post pictures of our local macroinvertebrates in an online encyclopedia. We spent our days picking up unsuspecting bugs, testing pH, and generally monitoring the health of Little Falls Creek, which ran behind the school. The program evolved to include a focus on the restoration of shad — salmon’s East Coast ecological cousin — in the Chesapeake Bay. No mention was made about why the shad population had plummeted to near extinction. No mention was made of the peoples, for whom most of the rivers and bays themselves were named. But, over time, and with concerted efforts, the population of these fish rebounded.

As I later reflected on that creek, which I knew and loved, I realized that it was only a small portion of that creek that I cared for. A few hundred yards downstream, on its long journey to the Chesapeake Bay, the creek had been channelized. It ran an inch deep, as a uniform trickle in the bottom of a concrete waterway with steep slopes and no vegetation. It went from its natural — albeit suburban — form, into a mechanized, managed chute, unrelated to everything that it slipped past. There were few birds, no more plants, no more small fish, and few, if any, macroinverebrates. Where we measured the creek, we called it healthy; where we did not measure, it was on the equivalent of life support.

I share this story not from a place of sentimentality, but because it offers a reflection of our times. Water is an old and powerful source of reflection. In the time before mirrors, it may have been in the still pond where we first came to see ourselves as humans. So what image does this small-stream-turned-storm-gutter offer back, nearly two decades later? When I look, I see a window into the pipeline world, meeting something less tamed, and more wild. I see a small story of what is happening at Standing Rock, and dozens, if not hundreds of other places across the globe. I see how caring for our little creek, when our baseline lifestyle sends its consequences downstream, geographically or over the generations, is not enough. What happens at Standing Rock affects us all, as we are all in relationship with one another. I see also that we are at turning point, a fork in the river. We are standing at the place where the creek just beyond our vision, just beyond our imagination, either continues to run wild, or falls under the control of human logic and straight lines. We are living in the crossroads of what some have called The Great Unraveling, and The Great Turning. We are simultaneously building and walking the bridge of what might well be named The Great Awakening. It is the awakening to inherent, and inherited relationship. It is the awakening to our grief, of what has happened, and the joy of what is, and can be. It is the remembrance that, as part of the earth, this powerful earth, what we do matters. I am not in control, but I am in relationship. And so, like so many eager shad, perched in the rough waves at the river mouth of our evolution as a planet, it is from this story, and this understanding, and this responsibility, from which my decision to go to Standing Rock stems. It was as much a decision to let go, as it was a decision to go. What follows are stories from that journey.

A BRIEF OVERVIEW

Although many have been finding ways to follow the story of Standing Rock, the limited media coverage and complexity of the story warrant a brief overview of what exactly Standing Rock is, before sharing stories of what happened when I was there.

Standing Rock is the name of the sixth largest Native American Reservation in North America. It is a remnant of the Great Sioux Reservation. The camps, to which most people refer when they say, “Standing Rock,” are actually four independent and interrelated camps, one of which was shut down. These camps partially overlap the border of the reservation and abut the Missouri River and the Cannonball River.

In August, the International Indigenous Youth Council sent runners to Washington, D.C. in protest of the 1,168-mile-long pipeline Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL). Their efforts are largely responsible for the movement that is now underway to defend the water and the sovereignty of the local tribes from the threats carried by the pipeline designed to carry fracked oil across four states and under the Missouri River. Oceti Sakowin (Och-et-eeshak-oh-win), the largest camp, is named for the Lakota title for the people commonly known as the Sioux. It means Seven Council Fires, and refers to the various, connected tribes within the region. The last time the Seven Council Fires met was in 1876, for the Battle of Greasy Grass, where Custer was defeated.

At its core, Standing Rock is a prayer camp, rooted in the protection of water and Indigenous sovereignty, not simply a protest against big oil and DAPL. The solidarity has grown, and the camps host an unprecedented gathering of more than 300 Indigenous tribes and thousands of other people from around the world. As such, it is the largest show of trans-national indigenous solidarity that has ever happened. This alone is cause for paying close attention and offering support, but the significance runs even more deeply.

Part of why this river, this reservation, and this moment are so important, is because it is a physical crossroads between the old story and the new story, where the history, the gift, and the wound, are tightly bound to one another in a microcosm of the larger story of this continent and the planet. The Missouri River is the longest river in North America and a major water source for the millions of people who live within its watershed. But, it is also an artery in the great body of this continent, known to many of its Indigenous Peoples as Turtle Island. It is at this encampment, alongside this river, where the artery finds its still pumping heart. This is the land of the Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota nations, the tribes of the Great Plains. This is the homeland of the legendary buffalo herds, some of the most fertile land on the planet, and prominent Native American tribes who have retained vibrant threads of their culture, and even shared them back out with the world, despite centuries of concerted efforts by some to wipe out their population, language, and lifeways. This is the land where hearts are buried at the site of the Wounded Knee massacre. This is the land of the Black Hills, where the faces of four white men — foreign invaders in the eyes of some — were blasted into the side of one of the most sacred sites of the Lakota people. These are the hills that the U.S. government illegally tried to purchase in 1877, upon discovery of gold in them. But, these hills, like Turtle Island, were never for sale in the first place, and the money sits, uncollected and accumulating interest in a bank account somewhere. Suffice to say, this place in particular has a history that is rife with complexity and importance.

Sadly, the general arc of the history of Standing Rock is not unique, but so far, the movement there is. It lies at the heart of what is being healed, and what needs to be healed. To put it succinctly, at Standing Rock, on the banks of the Missouri and Cannonball Rivers, is a seed planting in the birth of a new culture, from the ashes of the old fires. It is this context — of colonization, genocide, and centuries-long resistance—a context way larger than any one pipeline, corporation, or even climate change, within which these stories rightly sit.

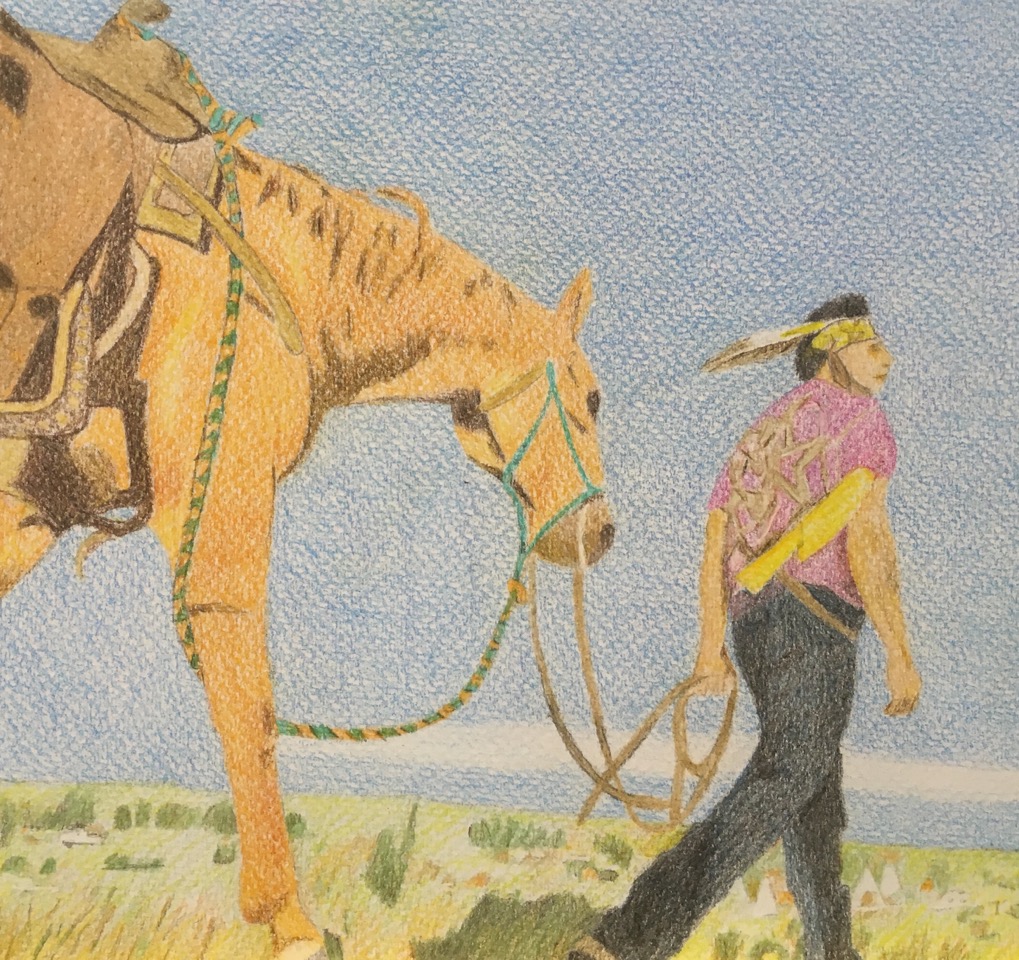

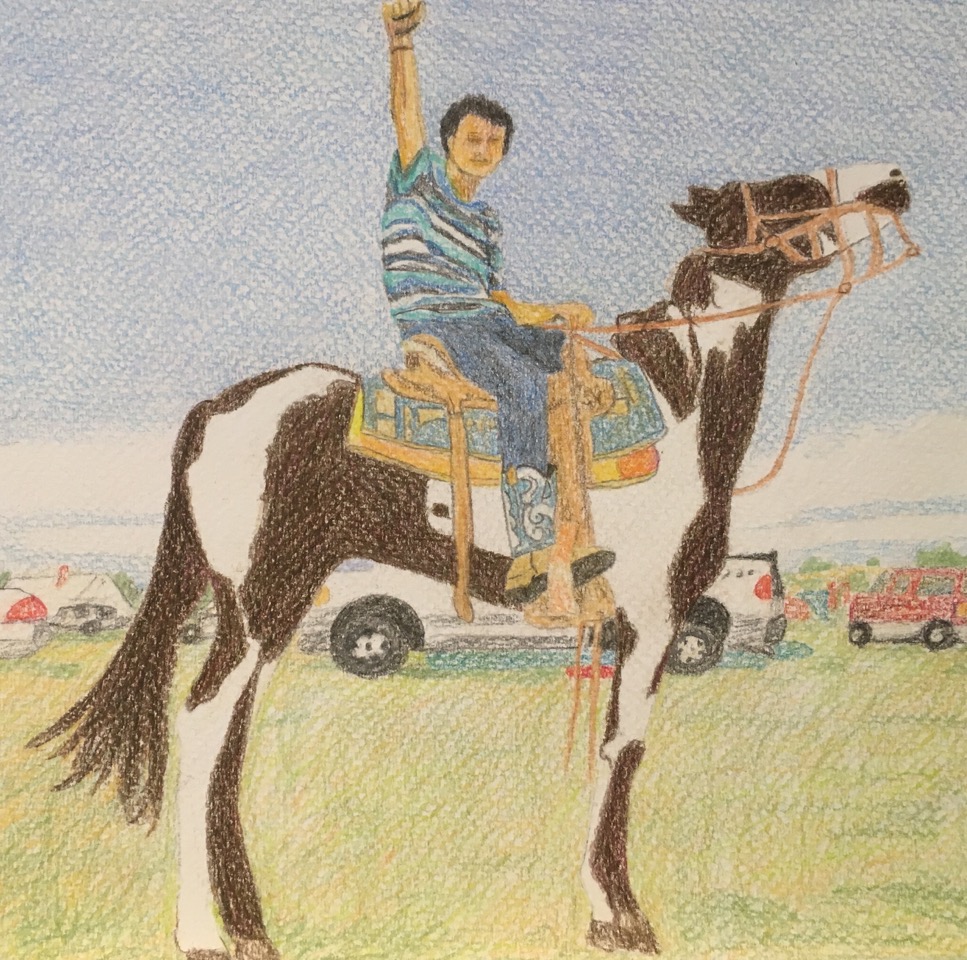

Original Artwork by Chip Romer: Each piece in the series is accompanied by original drawings by Chip Romer, the Executive Director of Credo High School in Rohnert Park, where Brendan currently teaches. In the fall, when Brendan shared with the administration that he planned to go to Standing Rock, he assumed that he would have to quit his job. Instead, they asked him to go as an ambassador for the school. The drawings are part of a series that Chip began while Brendan was at Standing Rock. They are a mediation, a reflection, and a prayer. The series is called, “Pictures of Resistance.” They are being shown publicly here for the first time, alongside Brendan’s writing.

Header image via Dark Sevier