On February 26, 2015, Aaron Tugendhaft saw his Facebook feed overrun by posts of a video of ISIS members smashing pre-Islamic sculptures in Iraq’s Mosul Museum. The video seemed paradoxical. If ISIS wanted to eradicate heretical art, why had they filmed themselves doing so, edited the footage, added a catchy soundtrack, and then uploaded it to the internet so that millions of viewers could catch a glimpse of the antiquities? Why did these self-proclaimed iconoclasts, destroyers of images, create new images that preserved in digital form what they had physically destroyed?

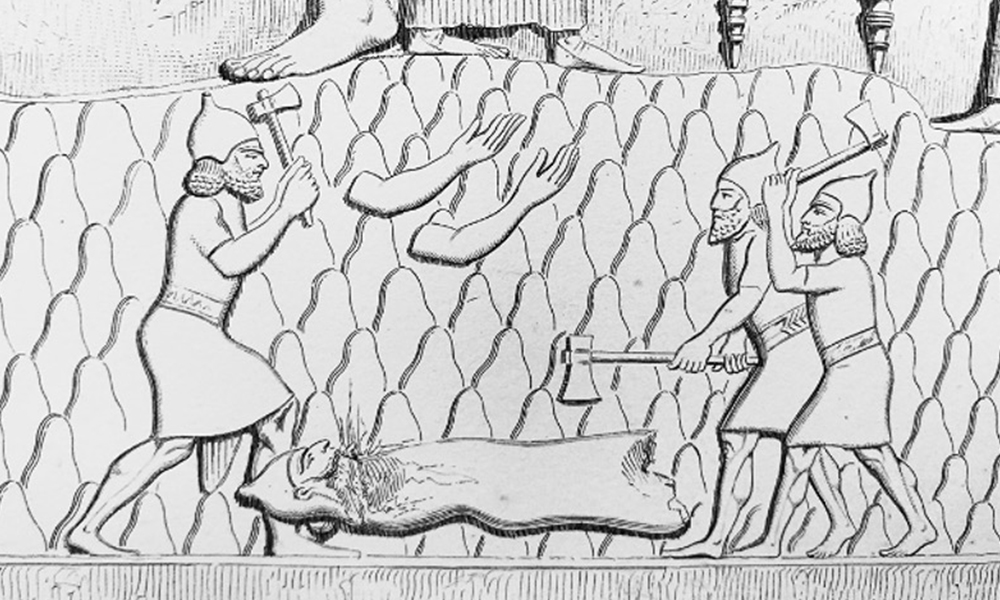

Tugendhaft, a scholar of the art history, religion, and political philosophies of the ancient Middle East, recognized a curious synchronicity of images. The ISIS video featured slow-motion shots of three men attacking a fallen statue with sledgehammers. Tugendhaft recalled a very similar composition in a stone relief from the walls of the palace of the Assyrian king Sargon II, showing three soldiers smashing a fallen sculpture of a conquered ruler.

Tugendhaft has written a book, The Idols of ISIS: From Assyria to the Internet (University of Chicago, 2020) spurred by the similarities of these two images, which are separated by 2,500 years but motivated by similar beliefs about the role of images in our lives. His rich yet readable book puts ISIS’ smashing of ancient sculptures into historical and political context. And Tugendhaft’s analysis of our “persistent drive to destroy images — and to make other images showing their destruction” comes at a time when the media is once again flooded with images of destruction of art — this time, of the statues being toppled by protestors around the world. Tugendhaft’s book is extremely relevant to America’s current debates about public sculpture, especially with regard to the role of violence in this debate.

Tugendhaft points out that many iconoclasts who have smashed art have seemed to thwart their mission “by commemorating the act of destruction.” Seeking to destroy an image of a fallen ruler, or rebelling against the use of images to teach what they consider false beliefs, iconoclasts have long been unable to resist the urge to create new images showing what it is that they have destroyed. Tugendhaft regards this not as naiveté but as an astute realization that images play a crucial role in our ability to live together as communities.

Drawing on the political philosophies of a range of theorists from Max Weber to Plato to the 10th-century Baghdadi philosopher Abu Nasr al-Farabi, Tugendhaft proposes that communities work only when their members sufficiently agree about what is good and what is evil. Because humans generally think in concrete examples rather that abstract theories, we need images to externalize and shape our communal ideals and fears. Ask us about courage and we see Harriet Tubman; ask us about evil and we see the closing doors of a gas chamber. Such images unite us by glossing over just enough of our individual differences to persuade us to take collective action. (Although Tugendhaft focuses on visual images in his book, his theory covers music, poetry, television shows, memes, and anything else that casts abstract theories of good and evil into tangible, memorable specifics.)

Tugendhaft demonstrates his point about the role of images in politics in a number of crisp examples. He describes Saddam Hussein’s use of ancient imagery, including a billboard showing him dressed like an Assyrian king hunting lions from a chariot. Tugendhaft also visually analyzes ISIS propaganda videos to show that they are constructed to look like first-person shooter video games (modestly noting that he had to hire one of his students to play them for him). In turn, these games were modelled on the images of the Gulf War captured by camera-equipped smart bombs, so that “ISIS videos imitate video games that are themselves imitations of the real world.”

But what happens when images collide? Just as we all have differing individual interests, we all have different images that summarize our views of the world. We must reconcile competing images as well as competing interests to be able to live together. One way to get around these conflicts is to trust someone, whether a dictator or a prophet supposedly speaking for a deity, to provide a unified truth we must all follow. Another way is to work out our conflicts to a compromise.

The frustrations of the latter approach mean that people often wish to flee to the certainty of the former — but Tugendhaft is acutely sensitive to the importance of holding space for disagreement within a polity. His grandfather was born in Baghdad, a member of the Jewish community “that had called the banks of the Tigris home since antiquity.” But the 20th century saw the tolerance for pluralism in Iraq shrink. Tugendhaft’s family fled in the wake of the Farhud, a pogrom carried out against Baghdad’s Jewish population in June 1941. Saddam Hussein and then ISIS carried this urge toward unification still further, seeking to stamp out any dissent. This crackdown on alternate beliefs often included image-breaking.

Smashing statues to change people’s minds is hardly new. Religious texts are full of stories of iconoclastic prophets. Tugendhaft discusses Moses burning the Golden Calf and Muhammed’s adventures in idol-toppling. Ibrahim provides the wittiest example. The Qurʾan describes him sneaking into a shrine and smashing all the statues except the largest. When put on trial, Ibrahim claimed the big statue had broken all the rest. He recommends his accusers ask the statue what happened. When they scoff, saying that idols can’t talk, Ibrahim carries the day by pointing out that they should be ashamed for worshipping things that can’t even speak.

Tugendhaft deftly lays out the differences between a community whose members can critically evaluate and change their guiding images and one whose leader seeks a “monopoly on truth,” framing any opposition to the community’s guiding images as insurgence. This theory of images is playing out all too clearly these days. As statues honoring slave-owners fell, Trump issued an Executive Order in June calling the protestors “violent extremists” who want to “erase from the public mind any suggestion that our past may be worth honoring.” Trump, like Tugendhaft, knows that calling for new images is part and parcel of calling for new leaders.

But what new images should fill America’s empty pedestals? Tugendhaft’s theory of the role of iconoclasm in political life can help us understand these protests against statues – and, even more importantly – can give us ideas for what sort of replacement monuments will encourage us to question dictatorial authority instead of merely re-solidifying it in a new form. Tugendhaft points out that ISIS’ images “are purposefully brutal; they seek to compel people to take sides.” But is only in the space between sides, in what Hannah Arendt called the public realm, that we can have the debate that leads to compromise and thus to community action. We need the type of monuments that will encourage debate rather than merely locking in a new certainty about good and evil.

Just as Americans are now arguing, sometimes with fatal consequences, about what public monuments should remain standing, we will argue about new monuments. Tugendhaft’s book is an important reminder that, if these arguments are democratic, we will never all be satisfied by their results. A communal compromise cannot fill all individual needs. The best we can hope for are monuments that leave open questions of what exactly it is that we should aspire to. Only a few of our current monuments do this, probably because they leave so many Americans infuriated — remember the vicious debates about Maya Lin’s masterfully ambivalent Vietnam Memorial.

Tugendhaft recommends that we all do what he has done in his book: “To be free citizens, we need to think about how our political images arose, why they were chosen, and what they leave out.” Americans have many decades of such thoughts about our public monuments ahead of us.

Top image: Assyrian soldiers smashing the sculpture of a conquered king. Drawing of a lost relief from Sargon II’s 8th-century BCE palace at Khorsabad, in what is now Iraq.