Halfway through Édouard Louis’ autobiographical debut The End of Eddy, the nine-year-old Eddy is raped by his 15-year-old cousin, face down in the sawdust that carpets the floor of his parents’ shed. The scene is even more shocking for the disquieting combination of Gallic frankness and childish innocence with which Louis recounts his first sexual experience.

A few days earlier, one of Eddy’s friends had discovered a porn film and suggested the four boys watch it and masturbate together. Later, his cousin Stéphane decides they will re-enact it for themselves. Eddy, who is already tortured by the incompatibility of his nascent homosexuality with the toxic masculinity of his milieu, is made to play the woman. “What I thought didn’t matter much. Decisions were, as was always and everywhere the case, the prerogative of men, and I wasn’t one of them.” For the other boys, the series of illicit meetings that follows is just a game, “like the days on which Bruno would amuse himself by torturing his mother’s chickens.” But Eddy is propelled into the situation by repressed desire for the older boys and an element of determinism: “I obeyed his orders with the sense that I was turning into what I had always been.”

Édouard Louis grew up in Hallencourt, a factory town in northern France, and published The End of Eddy (En finir avec Eddy Bellegueule) in 2014, when he was still just 21 years old. A powerful exploration of growing up gay in a macho, working-class society, The End of Eddy went on to sell 300,000 copies and cemented his reputation as one of France’s leading literary lights. Strongly influenced by the theories of the philosopher and social scientist Pierre Bourdieu, Louis’ work (he changed his name from Eddy Bellegueule to Édouard Louis to mark a break with his past) belongs to the same tradition of socio-political autofiction as Annie Ernaux and Didier Eribon.

Like Ernaux and Eribon, one of the most powerful currents running through Louis’ writing is shame: shame about his sexuality, and shame when his mother discovers her son being penetrated by his cousin and blames Eddy. And later, when he goes to university in Paris, shame of his working-class origins. Eribon once wrote that “shame about where we come from never leaves us”; Louis himself has claimed that it was easier to write about being gay than working-class. This is the France out of which the Gilets Jaunes were born, protesting the yawning chasm between the center and the periphery.

In The End of Eddy, the lives of the people of Hallencourt are poisoned by rage, alcohol, and toxic masculinity. Anyone who does well at school is considered a “faggot, fairy, cocksucker” because submitting to the teachers is a feminine act. “Real men” do not bow to authority. This hegemonic masculinity is a behavioral prison characterized by violence — sexual, physical, emotional, personal, political, systemic violence. Throughout his upbringing, Louis is persistently and brutally victimized, with daily beatings at school, and the humiliating fury of his parents who cannot understand why he does not behave like a “real man.” Even the way in which people express themselves verbally is violent, replete with casual racism, homophobic slurs, and crude slang. This spoken violence, represented as reported speech in italics, peppers Louis’ crisp, matter-of-fact narration.

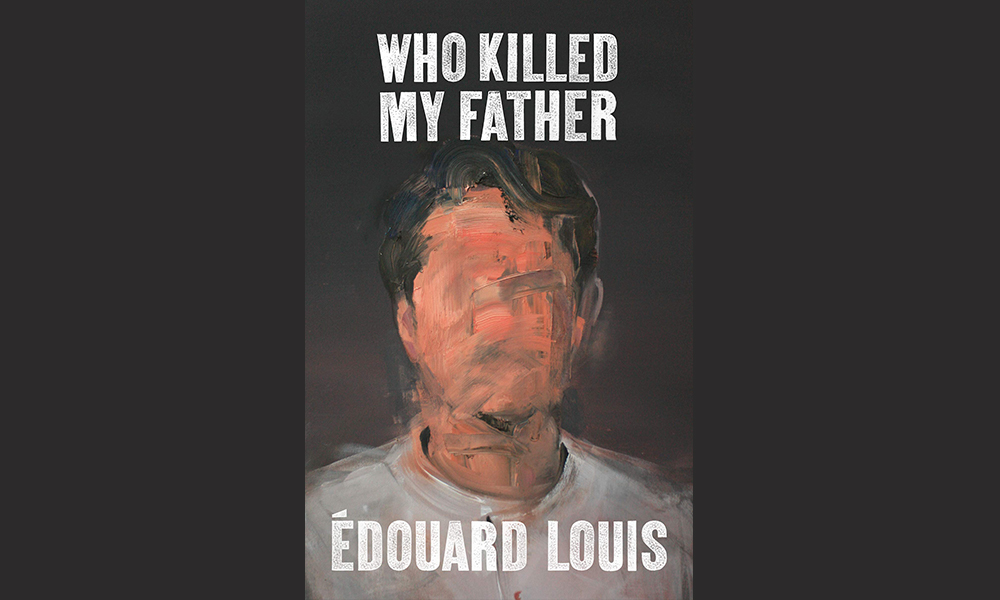

Louis’ formative years may have been almost indescribably bleak, but he is not the only one who suffers. His second work, Who Killed My Father (Qui a tué mon père?), holds a mirror up to the inequality and hardship meted out by the French state on poor, hard-working people like Louis’ father. It is a slim, incisive volume, addressed to his father in the second person, almost in the form of a theatre monologue.

Louis’ father worked in a factory all his life, until his back was crushed under the weight of a heavy falling object. After the accident, Louis’ father spent months in agony confined to his bed until, in 2009, the government of Nicolas Sarkozy replaced the basic unemployment benefit with one that was supposed to “incentivize a return to employment.” “In truth,” Louis writes, “from that moment on, the state harassed you to go back to work, despite your disastrous unfitness, despite what the factory had done to you”. The jobs offered were all exhausting, manual labor, forty kilometers away; just getting to and from work cost 300 euros a month in petrol. Louis’ father has no choice but to take a job as street sweeper, bent double over his broom.

The broken body of Louis’ father is represented as a site of political violence, for which Louis holds the state responsible. He points a withering finger at the policies of successive governments; in August 2017, for example, Macron’s government withdrew five euros per month from the most vulnerable people in France. At the same time, it announced a tax cut for the wealthiest. “Macron’s government explains that five euros per month is nothing. They have no idea… Macron is taking the bread out of your mouth”. His father is stripped of his agency by a hierarchical capitalist system shored up by entrenched systemic inequality:

The fact that you can hardly move or breathe, that you can’t live without the assistance of a machine, are largely the result of a life of repetitive motions at the factory, then of bending over for eight hours a day, every day, to sweep the streets… Hollande, Valls and El Khomri asphyxiated you.

Louis names and shames Emmanuel Macron, François Hollande, Manuel Valls, Mariam El Khomri, Nicolas Sarkozy, Jacques Chirac, and Xavier Bertrand. “The history of your body is the history of these names, one after another, destroying you. The history of your body stands as an accusation against political history.” Louis’ searing criticism of the political establishment echoes Émile Zola’s bold, brilliant diatribe J’Accuse in 1898: following the unlawful imprisonment of Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish army officer wrongly sentenced for spying, Zola wrote an open letter to the President accusing the government of appalling anti-Semitism. Like Zola’s J’Accuse, Who Killed My Father is a social call to arms — and a shatteringly audible one at that.

The residents of Hallencourt are trapped in a delirious cycle of boredom and poverty, with violent and painful consequences. They are victims of 30 years of welfare cuts and labor laws, of oppressive gender norms and the crushing lack of opportunity, of poor working conditions and the disdain of the political elite. This political violence is internalized, and reproduced as physical violence, as they lash out in an attempt to claim some agency over their lives. The men drink too much, fight, beat their women, set fire to cars and end up in prison. As someone who does not fit the mold, the effeminate Louis is often on the receiving end. The opening line — “From my childhood I have no happy memories” — says it all.

At times, the intense misery makes Louis’ work hard to read. But in blaming the state and the system, Louis shifts the responsibility from the personal to the political and exculpates the individuals. After everything that happened, this ability to write with dispassionate calm, free from judgement or resentment, is astonishing. Louis has spoken of the necessary, cathartic, role of writing in disentangling him from his past. For the reader, Louis’s work is an important reminder that privilege insulates you from politics; for the middle classes, politics can be spoken about in abstract and theoretical terms. But for the working classes, it is a different matter. “For the ruling class, in general, politics is a question of aesthetics: a way of seeing themselves, of seeing the world, of constructing a personality. For us it was life or death.”