Every Dwayne Johnson film is about his body. In a celebrity culture in which the physique of the male action star has been radically augmented, making the Supermans of previous generations look more like pre-serum Steve Rogers than Captain America, Johnson seems to tip the scales. He’s startlingly huge, his body a six-foot-four monument to the labor he documents in workout videos on social media. The Rock stands for hard work, work that hardens, flesh solidified to rock — which is also the work that builds the body, like a home forged in a rock face, cut and chiseled.

Johnson’s films find ways to keep drawing our attention to his body. Last year’s Jumanji reboot, Welcome to the Jungle, reimagines the original Jumanji board game as a video game. A timid teenage geek is sucked into the game and into the body of his avatar, Smolder Bravestone, played by Johnson (Bravestone, Braverock). The body swap allows Johnson to act against type: “Don’t cry, don’t cry,” Bravestone wills himself when things get hairy. It also centers Johnson’s body as an object of wonder, as when we see him discover his own biceps. Johnson pokes his own arm, gasps, and makes the muscle pose new. The refiguring of the nerd as the action hero becomes an allegory for the transformation of the built body.

This emphasis on a body that we can’t help but look at suggests how the Rock’s physique is also a problem to be negotiated within contemporary racial politics. As Richard Dyer argues in White, a study of the representation of whiteness in Western visual culture, the culture of bodybuilding is inherently racialized. The built body’s hard surfaces evoke a “sense of separation” that can be seen as a defense against mergers with “other” bodies, the bodies of those who aren’t white (or male). But the logic of bodybuilding undoes itself. Even as the built body tries to seal off the “pure” white body, its essentialism about race is undermined, Dyer says, by the “triumph of mind over matter, of imagination over flesh” that the built body materializes. The practice of bodybuilding locates racial difference not in immutable essences but in mutable surfaces; this concept of identity as moldable can be appropriated by those whose bodies are excluded by white bodybuilding culture. Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle isn’t clever enough to realize it, but its staging of a white body that shapeshifts into a built black body plays out the corporeal transformation the Rock exemplifies.

Johnson’s body might hack white racist discourse, but it’s also subject to it. Black men have long been depicted as violent brutes, creatures of superhuman strength and extreme aggression. Once, the New York Times spread news of “insane Negro giants” running rampart in the city, and black men were routinely lynched for their alleged assaults of white women. These racist stereotypes are reticulated in the testimony of police officer Darren Wilson who, in August 2014 in Ferguson, Missouri, shot and killed unarmed teenager Michael Brown. Wilson is the same height as Dwayne Johnson, and only 20 pounds lighter, but he told the Grand Jury that when he tried to grab Brown, “I felt like a five-year-old holding onto Hulk Hogan.” In a police interview, Wilson claimed that Brown had made “a grunting noise” and charged at him through bullet fire with “the most intense, aggressive face I’ve ever seen on a person.”

Grunting, hulkish: as is made clear by Brown’s horrific and senseless death, the risks of being a black man in America only increase when you’re a big black man. Earlier this month, the actor Terry Crews was asked by a member of the State Judiciary Committee why he, as “a big powerful man,” didn’t retaliate physically against the man he alleges sexually assaulted him. “As a black man in America…you only have a few chances to make yourself a viable member of the community,” he said. “I have seen many, many black men who were provoked into violence, and they were imprisoned, or they were killed. […] My wife, for years, prepared me. She said, if you ever get goaded…don’t do it, don’t be violent.”

Crews, like Johnson, must manage not only his behavior but also his star persona to mitigate the threat of his built black body. On screen and off, both of these men present as gentlemen, family men; they are principled, amiable, and even-keeled. This explains why Johnson felt so poorly cast in this year’s Rampage, in which he plays a primatologist who prefers the company of gorillas to people. The problem, as Alissa Wilkinson notes, is that Johnson is so affable that he “absolutely cannot telegraph a dislike of people.”

I’m not suggesting that these guys aren’t good guys. It’s just that they don’t have much choice but to be the good guys, because their awe-inspiring bodies carry the weight of decades of negative depictions of black masculinity.

¤

Rampage sees Johnson’s Davis Okoye racing after his best buddy, the gorilla George, after the ape is infected with a gene mutation that swells his form and stokes his rage. To set a black man among a family of apes, as the film does in the San Diego Wildlife Sanctuary at its opening, is to flirt with the highly problematic association between blackness and animality — although violent impulses are seen as natural to neither George nor Okoye.

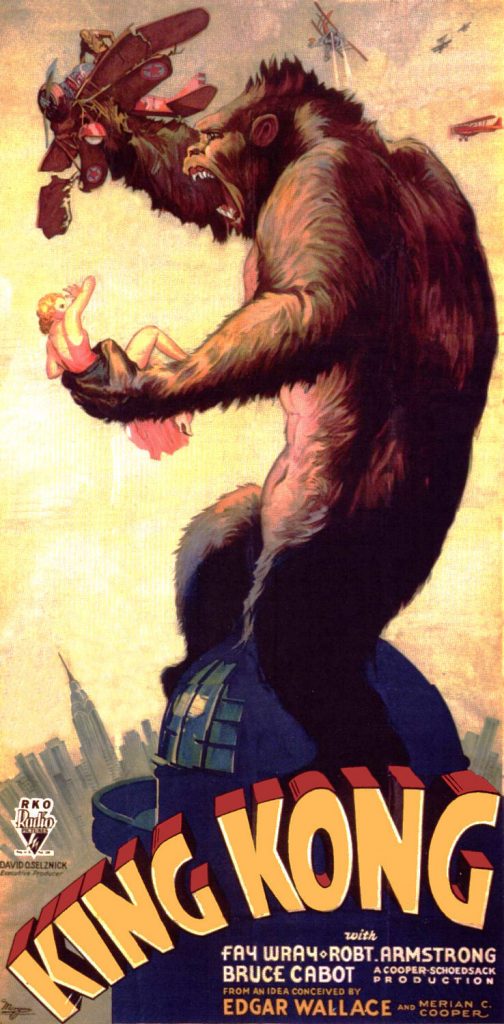

Still, the mutation of the gorilla into a rampaging killer reminded me of that most iconic of all murderous apes: King Kong. A huge box office success in 1933, King Kong was ground-breaking in its use of special effects (stop-motion animation, rear projection, matte-painting, miniatures), and one of its enduring pleasures is how it manages to be both highly artificial and affecting. I always cringe when Kong, battling various awkward-limbed predators on Skull Island, snaps the jaw of a dinosaur with his paws.

King Kong looks less than naturalistic to us today, but as with many horror and action films, then and now, the film’s success was always dependent on the willingness of its viewers to suspend belief. King Kong is known especially for its uneven treatment of scale: Kong looks about 18 feet tall in the jungle scenes, but he looks closer to 24 when he’s loose in Manhattan. The enlargement was necessary because the studio’s model of the tip of the Empire State Building, the setting for the showdown between Kong and the police circling in helicopters, was almost as big as the real thing.

If George’s rapid growth in Rampage recalls Kong’s six-foot spurt in the journey from Skull Island to New York, it does so even more obviously once George, too, travels to a major American city — this time Chicago — and to the top of a skyscraper. The giant ape, along with a crocodile and a wolf also altered by the gene mutation, is lured to the top of the Willis Tower, the headquarters of the corporation that illegally engineered the pathogen. Heading to the roof, Okoye manages to trick the raging George into taking a counter-serum before escaping in a helicopter as the oversized animals topple the tower.

It’s common for modern action films to raise the stakes of the hero’s battle by elevating it to a rooftop, ratcheting up pressure with altitude. But Rampage’s high-rise scene reworks some of the major elements of King Kong’s finale. The drama of the 1933 film is driven by the filmmaker Carl Denham, a fictionalized version of imperialist ethnographer–adventurers such as Robert Flaherty, who travelled the world to capture “primitive” bodies on film. Denham goes to Skull Island to seize Kong’s image, but the cinematic spectacle becomes a theatrical one when he decides to capture Kong himself and display him on Broadway. Denham pulls back the curtain with a flourish: “Look at Kong, the eighth wonder of the world!” The world’s newest wonder, after the pyramids, the temples, the statues of Colossus and Zeus: this is Kong as manmade structure, Kong as a white fantasy of the black man, made solid, shaped as a hulk. It’s Kong as rock, huge and inhuman.

The construction of the giant gorilla as bankable “wonder” is literalized in Rampage’s George, the product of corrupt corporate-scientistic power. When gorillas get big and ugly, it’s the white guys (and girls) who are responsible. In King Kong, Kong’s unveiling on Broadway and his last stand atop the Empire State consummate the film’s racial allegory, doubling the spectacle lynchings of black men in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As Kong falls in love with Ann Darrow (Fay Wray), the blonde star of Denham’s production, he’s scripted as the black man who dares to pursue the white woman, expressing a desire forbidden by the (properly) unholy union of Social Darwinism and white supremacy. This script is discarded in Rampage, for obvious reasons; the film puts the big Johnson and the bigger gorilla on top of a tower to prove they’re the show’s heroes. A bullet-riddled Kong once dropped from the Empire State to his death; now it’s the Willis Tower that falls, making way for the black man and the gorilla to save the city.

The difference between King Kong and Rampage reflects the shifts in the representation of black men in Hollywood since the classical era — from the early interracial romances of Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier, to the comic likeability of Richard Pryor and Eddie Murphy, and, in the golden age of over-buff action stars, to Wesley Snipes. Snipes played a bunch of baddies in the late ’80s and early ’90s, but he secured his popularity as an action hero in 1993’s Passenger 57 (“Always bet on black”) and his greatest commercial success was his superhero turn in the Blade trilogy (1998–2004).

Johnson, however, is quite unlike Snipes. When the Rock took his act to the silver screen in the early 2000s, he basically dropped the cocky “heel” persona he’d perfected on WWF Superstars of Wrestling, and he’s moved further and further away from the grit, intensity, and volatility of action heroes past. The biggest action star of our time, whose total box office earnings are nearing an astonishing $10 billion, is a hero without edge. He rarely fires a gun; he’s always a good dad; his way to the top is the high road. A polished Rock, smooth as a pebble.

Yet Rampage is better understood as an extension of King Kong than a repudiation of it. For a film that so overtly packages racist ideology in the hyperbolic figure of Kong as well as in the banal representations of Skull Island’s “savages,” King Kong is remarkably bad at blocking our sympathy for the monster at its center. Kong’s acts of violence are repeatedly counterbalanced to pathetic touches in his portrayal. When Ann Darrow’s (other) suitor, Jack Driscoll, stabs Kong in the finger, the gorilla slumps to the ground like an overgrown child. When Kong shreds off Ann’s dress in strips, the suggestion of sexual assault is redirected as he gleefully starts tickling his captive. The island and the city echo with Ann’s screams, but the film troubles the idea of Kong’s villainy by his humor and relative guilelessness. Sure, these features are meant to suggest Kong’s place on the lower rungs of the evolutionary chain. But they also imbue him with a pathos that only deepens as he’s humiliated, hunted, and killed in New York.

King Kong’s fascination with the giant ape slides into a form of identification with him. It registers the monstrous black man as a white fabulation and it introduces the trope of the heroic black man, amiable, genial, and essentially good. He’s physically imposing and capable of violence, but only when it’s really necessary, when the woman he loves is in danger. Like George the gorilla; like Johnson’s lead roles. Rampage is another version of King Kong, and it’s a version that the earlier film already contains within itself.

¤

The skyscraper in Skyscraper, Johnson’s newest blockbuster, is a self-conscious mash-up of the Glass Tower in the 1973 disaster film Towering Inferno and the terrorist-crawled Nakatomi building in the 1988 action film Die Hard. Reaching up like a twisting silver arm into the skies above Hong Kong, the 225-storey skyscraper is named for the Pearl, a dome nestled at its peak that functions as a hall of mirrors, its surfaces lined with thousands of tiny cameras that feed images onto dozens of screens — a high-tech homage to the mirror scene in Bruce Lee’s Enter the Dragon.

Skyscraper, like the Pearl, is a vast reflective machine, its scenes flashing up other scenes from across cinema history. According to the Pearl’s businessman owner, the optical experience of the dome makes it “the eighth wonder of the world.” It’s a boast that asserts the power of the filmic illusions that the dome tropes. But it also returns us to Denham on Broadway, transported from one global city to another — a move also made by the advertisement for the Pearl, as it shows off the skyscraper’s size by superimposing its silhouette over that of the Empire State Building. The tower is three times larger than the one Kong surmounted: can the Rock reach its heights?

Johnson’s Will Sawyer, a former FBI agent, has been employed to assess the Pearl’s security systems. When a fire is started on the 96th floor by a group of mercenaries connected to an international crime syndicate, Sawyer’s wife and children are trapped inside the building, while Sawyer finds himself grounded, the prime suspect for the terrorist plot. Chased, like Kong, by the local police, Sawyer begins his ascent to the levels of the building cut off by the fire. He climbs a construction tower, launches himself across a precipice into a broken window, and then scales the partially destroyed skin of the skyscraper.

It’s a ridiculous, utterly enjoyable sequence — particularly since Sawyer is an amputee, and the film treats his prosthetic leg as an asset, a supplement to an already enhanced body. In King Kong, we don’t see the gorilla’s ascent; the film cuts away to the police station where the officers hear it reported on the radio. King Kong’s radio reports become Skyscraper’s television reports, the crowds of gaping pedestrians in Hong Kong, the mass of upraised camera phones, as Sawyer’s sky-high antics assemble an audience at street level that mimics the cinema audience, eyes pulled upwards by the thrill of impossible stunts performed by an impossible body. Skyscraper therefore recalibrates King Kong’s interest in the spectacle of the black body suspended — on a Broadway stage or a building — between horror and fascination, villain and hero.

But Skyscraper’s crowds, like its cinema audience, are the black man’s fans. They cheer when he navigates himself about the Pearl’s surface, when he wrenches himself into the building. The police might not be so sure, but the crowds recognize Sawyer as their hero. And so Skyscraper reorganizes the love triangle between Ann, Driscoll, and Kong in King Kong. Sawyer has been set up by his former FBI teammate, Ben (Pablo Schreiber), who blames him for a hostage situation that went wrong 10 years earlier. The incident left Sawyer an amputee, but, as he tells Ben, “without that bad luck I never would have met [my wife] Sarah. I don’t know who I’d be without my family.” Ben cuts him off: “You’d be me.” Later, after his betrayal of Sawyer has been revealed, Ben tells him, “You screw up, you get a whole new life — what do I get?”

Ben’s characterization isn’t exactly complex, but his anger boils down to jealousy over what Sawyer has and what he doesn’t: most specifically Sarah, played with gusto by Neve Campbell. Skyscraper is what happens when the white man is passed over and the black man gets to settle down with the white woman. Ben represents the anxieties over interracial love implicit in King Kong and explicit in Stanley Kramer’s Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? and its modern horror reimagining, Jordan Peele’s Get Out. Like Sidney Poitier and Daniel Kaluuya in those films, Sawyer is the unwelcome houseguest — and the house is Hollywood. When Kong escapes from the theater in King Kong, Ann whimpers to Driscoll, “It’s like a nightmare.” Hollywood nightmare becomes Hollywood romance as, at Skyscraper’s end, the pace slows, the music soars, and Sawyer embraces Sarah, encircled by a joyful crowd and flashing cameras lifted directly from Die Hard.

¤

It matters that our quintessential action hero — this year’s highest-paid actor — is black. Johnson’s films studiously avoid mentioning his race, but his blackness marks the outlines of his star persona — as it is shined up, made benignant, in both senses of the word, benevolent but also beneficial (or “viable” in society, as Terry Crews says). His blackness matters, because our on-screen archetypes shape how we see people in real life. Johnson offers an alternative model of black masculinity to a world where armed white men see unarmed black boys as unstoppable monsters.

And yet isn’t it telling that the Rock, who symbolizes hard work, has to work so hard to be our hero? How confined the space is for a black man to take the lead? The representation of women in many ’80s and ’90s action films looks wildly progressive these days. Compare Laura Dern’s badass, openly-feminist Ellie in 1993’s Jurassic Park with Bryce Dallas Howard’s Claire in 2015’s Jurassic World, demonized for being a childless professional, her heroic acts undercut by smug close-ups of her stilettos. There’s a similar shift from the era of Wesley Snipes to our own era, the era of the Rock. Snipes could shuttle between the eye-gouging violence of career criminal Simon Phoenix in Demolition Man and the airborne heroics of security expert John Cutter in Passenger 57. Even in the protagonist’s seat, Snipes has “a bad mouth and a bad attitude,” as Passenger 57’s tagline tells us. But when the Rock plays a security expert in the wrong place at the wrong time, as in Skyscraper, he plays him really, really nice.

That we want our Rock so buff, so buffed up, might well suggest that we’re still in thrall to a nightmare of black villainy, a racist vision of the big black man as Kong.