I was trying to get lost, running north on Hill Street, south of downtown Los Angeles, blasting the Black Panther soundtrack, when I saw the fighter. He must’ve been 24 feet tall. Blue-black-purple skin, gloves fat and red as maraschino cherries. Lips parted, his face was a topographical map, furrowed with cliffs and grit and gulfs — he was short a front tooth — with the exception of his eyes. His stare was flat and dense, gleaming with the alertness and intensity that is sister to euphoria.

The mural, done by @MADSTEEZ, otherwise known as Mark Paul Deren, spans the brick wall of City of Angeles Boxing. The gym is less than a mile from my apartment, yet in two years of living in this neighborhood, I’d never seen it before. It seemed that the universe thought now was the right time for me to see this boxer. After all, I’d been meditating on toughness, listening to Kendrick Lamar’s anthems, and thinking about the elation that comes with strength, largely because I was reading Life After Rugby by Eileen G’Sell.

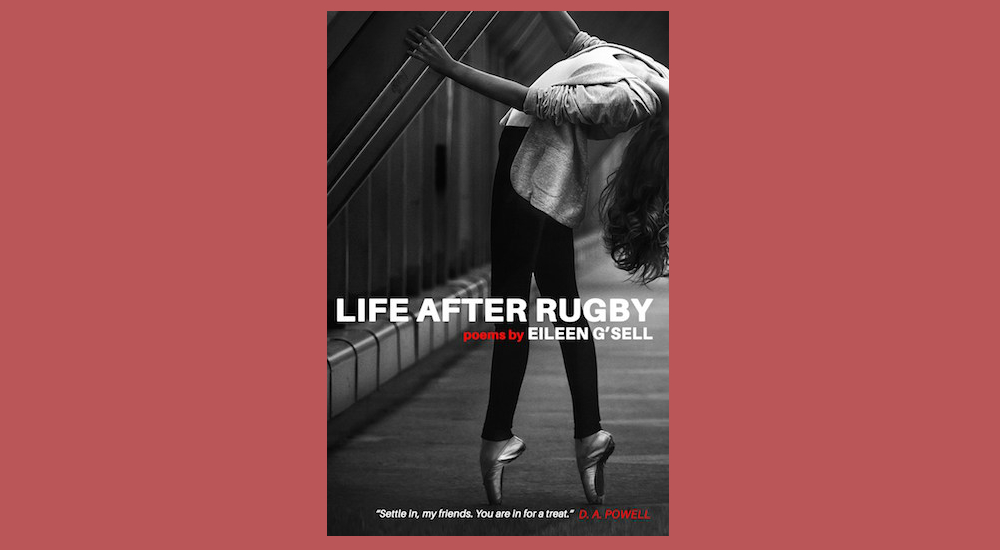

G’Sell’s debut collection of poetry, published in December by Gold Wake Press, is sneaky. It’s a slim book — 75 pages, four sections — and, at first glance, it might have you believe it’s delicate. The black-and-white cover photo shows a dancer arching her back, balanced en pointe. Only after chasing this image with the obdurate shot of the “rugby” part of the title does one remember the injuriousness of ballet, all those gorgeous busted toes. To be a ballerina on an urban bridge, gripping a girder rather than a barre, is to see how the book’s epigraph from Mike Tyson makes a lot of lyric sense.

“There’s nothing more deadly and proficient than a happy fighter,” Tyson says. G’Sell’s poems interrogate this thesis again and again. What does it mean to be proficient? Who are our fighters? What constitutes deadliness in the daily fights detailed in these poems? Isn’t it time we re-gendered tough? And isn’t it also time we relished the arduousness of practice, training, discipline, and focused work? “At best life is hard,” G’Sell writes. “At worst life is easy.”

Easiness, at least according to the ethos of these poems, is a missed opportunity. Here is a speaker who relishes a contest, a dare, a taunt. A challenge is always worth it, G’Sell seems to say, whether that challenge is driving across the country, finding a way to make a plane ride wildly entertaining, or tracking down a “room of Russian balloons” for a lover. This isn’t to say that the speaker is a schoolyard jock, spurring on meaningless games of one-upmanship. Most of these challenges and taunts seem to be self-directed, dares to oneself. Even emotions are recast as potential obstacles to overcome: “Sometimes I like to have feelings just because they are so impractical.” The challenges almost always boil down to an admonition to be … better. Realer, funnier, tougher, truthier.

Fueled by the urgency of these challenges, the speaker is bold and yet courteous in her declarations, ready to be at once awe-struck and ascertaining: “This place is weird, sexless, and white,” G’Sell observes in “Follow the Girl in the Red Boots”; it is the book’s first line. That assessment — “weird, sexless, and white” — introduces the reader to preoccupations central to Life After Rugby, namely the expectations of gender and normativity. Too often, G’Sell’s poems seem to suggest, we assume the “happy fighter” is a man.

Not so in Life After Rugby. To say that roles are reversed is to presume a binary that G’Sell’s worldview debunks over and over. Roles are personas and tools, meant to be adopted for the appropriate occasion, the way a boxer dons his gloves in the ring. “On quiet horses, the women and children are storming the city today,” G’Sell writes in “Women & Children.” In “Deep Space Dialectic,” which showcases G’Sell’s acumen as a cultural critic (she’s interviewed the likes of Isabelle Huppert and Aubrey Plaza), the feminist politics of the movie Alien are met with cheeky assessment: “The film’s true hero is Sigourney the Boss. She’s a Real Bitch”

Are you “supposed to” say “Real Bitch?” Who gets to decide? G’Sell’s diction isn’t so much reclamatory as wisely irreverent. “Deep Space Dialectic” presents a juxtaposition that appears throughout G’Sells work: the role of pop culture in an individual’s life and, namely, the guiding role of icons of toughness. “I want to tell you about power,” G’Sell asserts, and in doing so, she genuflects before icons of toughness, eliding gender and age and race: Mike Tyson is Sigourney Weaver is Clint Eastwood is Whoopi Goldberg is Whitney Houston.

Perhaps readers will find G’Sell’s work facile. Digestible, readable, slick. Indeed, she is almost ridiculously witty, each poem presenting a moment that would provide the reader with ample entree into a cocktail party conversation. But to see Life After Rugby as a series of pithy flirts is to miss the point. “I have made light of many things,” G’Sell writes, “and that’s why we can see in here.”

Like the boxer who’s always moving, butterflying about the ring, the speaker in these poems is nimble in her formal maneuvering. “What is it then to be on fire,” G’Sell asks, in “Whitney Houston Pronounced Dead at 48.” In this poem, an incomplete sonnet, the destructive power of the singer’s meteoric talent is elegized, marveled at and mourned, a gift that led her to “rocket/lucky forward.”

Despite the wit, the imagery, and the catchiness of pop culture, these axiomatic lines — so quotable, citable, meme-able, tattoo-able — continually showcase G’Sell’s “[refusal] to make this beautiful.” This, of course, is everything, but especially, as she notes in a recent interview with The Rumpus, suffering:

And so this question of “How do we aestheticize suffering? How do I aestheticize my own suffering?” is one that deeply interests me. How do filmmakers, artists, and poets aestheticize really dark periods in history and also personal suffering?

One way the athlete or the fighter aestheticizes suffering, Life After Rugby contests, is by fetishizing it. The boxing gloves, the dirty pointe shoes, the “red boots” become emblems of suffering, beautiful in their own warp and wear.

The more I spent time with G’Sell’s book, the more I think about the words of Jean Genet. In his essay “The Studio of Giacometti,” he wrote: “Beauty has no other origin than a wound, unique, different for each person, hidden or visible, that everyone keeps in himself, that he preserves and to which he withdraws when he wants to leave the world for a temporary but profound solitude.”

In Life After Rugby, G’Sell argues that those wounds are worth fighting for, that toughness knows no gender or politic. The fighter has breasts and pecs. To see the wound as fertile is to suggest that what is dangerous, lethal even, might also be potent.

I stopped and took a picture of the mural outside of that boxing gym on Hill Street. I stopped running to do so. The rest of the way home, I found myself trying to decide if the man in the mural looked like Mike Tyson. I thought he might. Still, it had been years — since childhood — since I’d seen him in action. I should’ve been traumatized watching such gruesomeness as a child, but I only had fond memories of Tyson’s teeth tearing at the flesh of Holyfield’s ear like an especially tough piece of beef jerky.