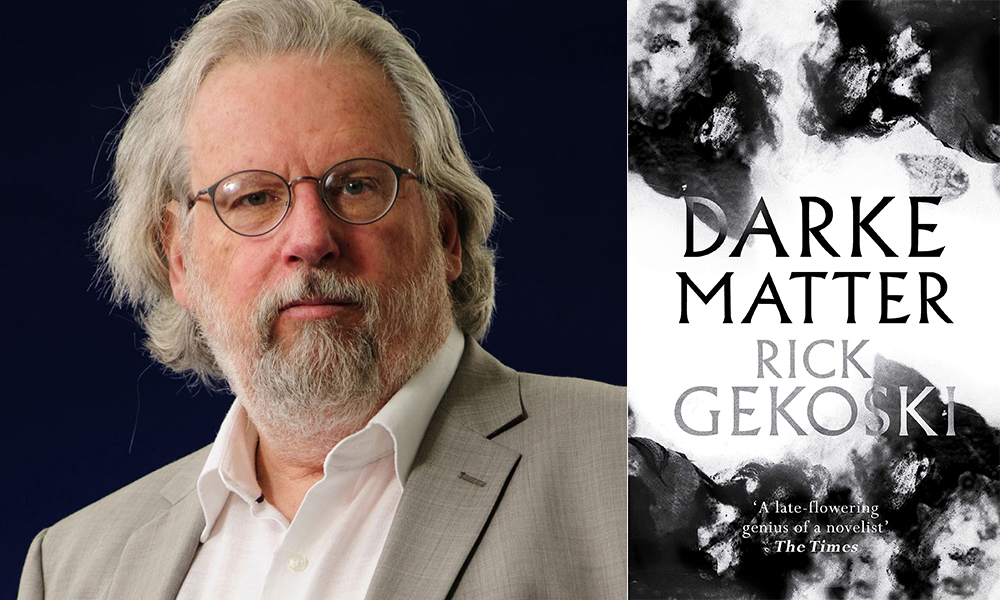

Rick Gekoski is a retired academic, former Booker prize judge and chair, broadcaster, bibliographer, private press publisher, journalist, and rare book dealer. His debut novel, Darke (2017) was prompted by an insistent inward voice, and its author was called “a late-flowering genius of a novelist” in The Times. This was followed by A Long Island Story, a fictionalized memoir of his childhood. Darke Matter, the sequel to his breakthrough novel, was published this year to considerable acclaim.

¤

ERIK MARTINY: James Darke, the eponymous narrator of Darke (2017) and its sequel Darke Matter (2020), is something of a contrarian. He makes anti-Irish, anti-Semitic remarks (among others) and is generally misanthropic and oppositional. The only thing he’s in favour of is global warming. Groucho Marx’s “whatever it is, I’m against it” comes to mind. Do you see this kind of attitude as typical of someone of his class and generation?

RICK GEKOSKI: James Darke is a crusty retired English schoolmaster from one of the great public (that is, private) schools. He is stuffed with detestations, quirky insults, and prejudices, which are by no means limited to the Jews and the Irish. He also hates (in no particular order) dogs, babies, food in cans or plastic, working class accents, Walter Scott, handymen, polyester clothing, angels, Christmas trees, indoor plants, Rupert Brooke, politicians and psychotherapists, reading groups, pelicans… Oh, and God. When he considers the seminal stories of the Old Testament — of Job, Abraham and Isaac — he is horrified. If God were God he would behave like God. As he doesn’t, he isn’t.

Like Swift’s Lemuel Gulliver, Darke is often disgusted by humankind. He is inwardly snarling a good deal of the time. If you met him you wouldn’t know this: an Oxbridge-educated, urbane, well-read, and witty man, we only know his inner world because we are reading his journal. The self-revelations are unseemly because not meant to be seen. He finds it more animating to dislike than to admire. He’s a great hater.

A critic in The Economist described James Darke as “odious.” Other readers loved him.

I think of him as pretty much normal.

You don’t foreground your Jewish heritage much compared to your peers, Philip Roth and Howard Jacobson. Do you consider yourself a Jewish author or does that kind of identity bear little on your work?

I am an author who is Jewish. I grew up on Long Island, went to the local Temple until my Bar Mitzvah, gathered my presents in my new leather bag, and never went back. Being Jewish is essential to my sense of who I am, but I don’t feel a need to practice. Not yet anyway.

After graduating from UPenn, I went up to Oxford in 1966: you always go up to Oxford and Cambridge, and when you “take” your degree, you go down. (The saying doesn’t stipulate on whom.) During those years doing post-graduate degrees in English and latterly teaching in the English Department at the University of Warwick, I was largely unaware of English antisemitism. I’d read about it, heard murmurs and rumors, but had almost no first-hand experience, until a new relative by marriage described me as “a typical New York Jew.” She’d never been to New York, and knew few enough Jews, but she knew a stereotype when she saw one. When I objected to the term, she had no idea that she’d said something offensive. She meant that I was very smart, loudly articulate, and probably sexually perverse. Philip Roth is good on the topic.

I suppose the most blatant exposure I’ve had to English antisemitism came, as you might suppose, if you thought of it — I hadn’t — through someone’s journal entries about me. And no, I’m not Mickey Sabbath, poking about salaciously in bedrooms looking for locked diaries. These journals were published by John Fowles, in two volumes, in 2003 and 2006. God knows why he chose to do so, except as evidence for, and in praise of, his own forthrightness. They are his last (ill)will and testament. The entries are frequently excoriating about his wife, and pretty tough on himself, as well as a serious proportion of the people he met, and (how crazy is this?) the publisher of the book itself, Tom Maschler, of Jonathan Cape. Maschler published most of Fowles’ major works, and counted him a life-long friend. Fowles account of him is so virulently anti-Semitic that Maschler never spoke to him again, and did not attend his funeral in 2005.

In 1988 I visited Fowles several times at his imposing, gloomy Regency house, overlooking the sea in Lyme Regis, first to buy some of his books and manuscripts, and latterly in the hope that he might contribute a foreword to a book I was considering publishing. I suppose we must have met three or four times, and the talk flowed, he was engaged by what we were doing, and pronounced himself pleased that we had met. So, when years later I opened his recently published diary, I wasn’t entirely surprised to find several references to myself, though I was by their nature. The incessant refrain was that Rick had behaved “like the Jewish book dealer he is,” and that he is “too Jewish for English tastes.” Yet he says he liked me, and discerned something Hollywoodish in my character: that place is full of smart, aggressive Jews! They should stay there!

So that’s what they’re thinking. When I once went to stay with William Golding in Cornwall, while working on the bibliography of his work, I quickly recognized a coded version of the same phenomenon. I had only met Golding once before, when I was chair of the arts faculty at my university, and had to look after him on the day he was granted an honorary degree. A few years later, when I visited the Goldings, Bill picked me up at the railway station in his old Jaguar. I admired it as we drove home.

“I’d love a new one,” he said, “but I can’t afford it.” It was the first of a number of his comments about being short of money. Once I saw his house and extensive gardens, and reflected about the lifetime royalties on Lord of the Flies, I rather doubted he was. After dinner and a lot of drink, I encouraged him to buy a new Jag.

“That’s very well for you to say,” he responded, “you’re a rich man!”

Practice makes perfect, and listening acutely sharpens the senses. I began, slowly, to understand a variety of subtexts in English discourse. In Darke, the protagonist, whom I took to be typical of his class and generation, is covertly anti-Semitic, and his journal entries refine and gleefully express such sentiments. Here he is, thinking about one of his least favorite students:

Anyway, Gold, as I remarked to one of my sceptical colleagues, is hardly a Jewish name.

He raised his eyebrows.

“Goldberg, originally, I’d bet. They used to change it to Gold, but people see through that one. Trying to pass. They often do.”

I was mildly irritated by this. Just because a boy is clever, attention-seeking, and physically uncoordinated doesn’t necessarily make him a Jew.

Later in the novel, when his wife has taken a Jewish lover, James is predictably sardonic:

I suspected that she had chosen him because he was Jewish — appetitive, highly educated, too self-confident — because she knew it would provoke me. I kept expecting her to start singing tunes from Fiddler on the Roof. If I were a rich man… She would have been delighted if I’d put framed Hamas posters in my study, or added The Protocols of the Elders of Zion to my bedside table. Something to show that I cared…

My (relatively young) editor objected to both passages, on the grounds that, if such views were attributable to an older English generation, they were not to his, and would both puzzle and antagonize many readers. He suggested cutting both passages. I did.

I regret it. Those phrases and perceptions seemed to me accurately observed, given that there is so much not to see. It’s so easy for an outsider, whether by class or nationality, to miss English antisemitism, which flourishes gently and poisonously not merely, as usually, in the shires, in Club-land, in the public schools, but latterly and more toxically in the left wing of the Labour Party.

James Darke’s words and behavior are carefully curated and fit for purpose. Trained at forms of dissimulation masked as good breeding, his true opinions emerge only in his journal. Here at least at last he can express himself as he is — not prejudiced and intemperate, he would regard both charges as stupid — but clear-sighted and unabashed. His opinions are often dismissive, to be sure, but they are often sentimental as well. Normal.

Dickens is foregrounded again in your latest novel Darke Matter. The narrator, James Darke, tries to find comfort in reading A Christmas Carol but is rebutted by Dickens’s Victorian sentimentality. Darke himself veers between overflowing sentimental love for his wife and cynicism with regard to most other people. To what extent is Darke as a character modelled on Dickens’s bipolar tendency to swing from dark humour to sentimentality?

James Darke’s “sentimental” love of his recently deceased wife is largely posthumous, a symptom of grief as much as a cause of it. People improve after they die. During their marriage he would never, being a reticent Englishman, have expressed the loving sentiments with which his diary is replete. His marriage to the writer Suzy Moulton was initially passionate, and morphed, as marriages often do, into a convenient, often warm often troubled, union of two adequately compatible souls.

I don’t think there’s much of Dickens in this. James Darke is a much better man, husband, and father than Dickens ever was. But Dickens was one of the young Darke’s touchstones, because he was moved by the oppositional spirit in the novelist — indeed, most of the great Victorian novelists were the greatest critics of their own age. Darke worked for some years on a little monograph — he was too modest to call it a book — on Dickens as an opponent of injustice. It was to be titled Indignations. But the more he reread his former mentor, the more he thought that, for every palpably oppositional sentiment, there were ten of pure schmaltz — a Yiddish word that it amuses Darke to use.

The two presiding spirits that hang over both Darke and your sequel Darke Matter are Dickens and Swift. While Darke seems to me to be more Dickensian in its radical bipolar swinging, Swift gets the upper hand in Darke Matter when the narrator decides to add an extra ending to Gulliver’s Travels to entertain his grandson and so he can get some reprieve from the outside world and his collapsing life. Do you too have a preference for Swift or was the motif of Gulliver-like seclusion prompted merely by Darke’s elegiac desire to retreat from the world of men?

In Darke Matter Dickens is an occasional figure of fun, but Swift comes front and center. The ostensible reason for this is that Darke’s grandson Rudy, like James’s former pupils, finds it frustrating that Gulliver’s Travels ends but never resolves. Gulliver has returned from the land of the Houhynmnms, palpably both saner (to himself) and madder (to everyone else), to reside with the horses in the stables of his former home, unable to bear the noxious company of his wife and family. That’s no way to finish a book! What happens next? The answer is provided in Book Five: A Voyage to Redrith, by James Darke, MA (Oxon), PhD (Cantab).

This story is also, of course, a form of memoir. James Darke has nursed his dying wife through the terminal stages of her lung cancer, wiped and mopped up, opened the window sufficiently to clear the air but not enough to jump out of. He witnesses her decline into emaciation and agony, gasping for every breath, hardly recognizable, yet mysteriously the same beautiful woman he has loved. He cannot bear it, but does. And when he has helped her to die, his heart and spirit collapse under the weight of what he has seen, done, and lost. Like Gulliver returned from Book Four, in which he meets the detestable, filthy and lascivious Yahoos — base versions of humans — Darke conceives a debilitating and apparently ineradicable disgust for the human body. If his Master the benevolent Houhynmnm recognizes in him some smattering of reason, it is eventually decided by the governing Council that he must be sent away. His congenital degradation cannot be denied or transformed.

Hence Gulliver, returned home to London; hence James Darke, returned from the death of his wife. Writing is James’ way back into the world: an attempt to explain, to condone, to be readmitted into the circle of love. In his extension to Gulliver’s Travels, which he reads aloud to Rudy, there is a happy ending, in which his family is reunited, moves to the country, and Captain Gulliver sees out his days. Rudy loves it.

James, of course, knows better. The chapter ends with his reflection, as he gazes at his sleeping, satisfied grandson:

Had Lucy [his daughter] been eavesdropping outside the bedroom door, she would have wept with astonishment that I was capable of composing such a heart-warming and consoling story. As do I.

This is what integrity is for, isn’t it? To be sacrificed again and again, abandoned in the services of love.

Darke clearly dislikes many aspects of the contemporary world he inhabits, its jargon, its narrow frame of mind. Would you say that he is backward-looking, or that he has a strong attachment to the values of the past?

James Darke is in his late 60s, and his personality has changed — he might say developed — from its early optimism and belief in the improving qualities of education into a contrary and oppositional force. Once a follower of the sages, his belief in what he now calls those “shitslingers” has been eroded by his life experience. He is a skeptic, and instinctively interrogates any proposition to see if it actually stands up. Is wide reading good for you? Look at the wide-readers, the writers, academics, and critics. Are they filled with sweetness and light? No, they’re no better than everyone else. Worse, really, inflated with righteousness and self-righteousness. T. S. Eliot is your model? Good luck! Darke has a lot of fun going through the pantheon of literature, dismissing and sneering at the pretentiousness of it. With exceptions (Dickinson, Stevens) he detests poets — death by droning — and though he joins a poetry group, he loathes it, and soon resigns.

When the third and final Darke volume eventually appears (I hope in 2022), James will have entered the contemporary world, with its idées fixes about, well, everything: its fanatical dislike of opposition, its shouting down of other voices, the rampant righteousness and hatred of anyone who dares to express a contrary view. Cancelling, de-platforming, shaming… James was raised in a literary culture that positively encouraged opposition, and one of his touchstones is John Stuart Mill, with his reminder that it is those with whom we most disagree to whom we should pay most attention. Unless you can hone your arguments by and through listening attentively to counterarguments, you can never learn anything, or develop, or self-criticize.

I recently asked my literary agent if James Darke, a fictional character, might be allowed to have contrary opinions about some of the hot topics du jour. As I began to enumerate some of the subjects, he cut me off. I could sense a shudder.

“No!” he said. “Young publishers and agents are very sensitive on such matters, and no one would publish a contrarian book about them.”

I’m now trying to figure out how to allow dear James Darke to continue to say what he has to say, in his usually acerbic manner. I have one or two ideas — ways of deflecting the focus — but none of them have the ring of truth. “Ring of truth?” Freely expressed, debatable, cards-and-ideas on the table? Ha fucking ha.

And no, I’m not a mouthy right winger. I have liberal antecedents and beliefs, derived from the happy days when “liberal” was not a frequent term of contempt. But my fictional character is outspoken on the subjects that most offend his sensibilities. He hates slogans, detests group-think, abhors popular movements. He likes sharing ideas, and interrogating them. He knows little of social media, and would writhe in agony if he were exposed to it. Yet in Darke Matter, James reluctantly agrees to open a Twitter account and website, to circularize his thoughts about assisted dying. His profile describes him as ACCUSED OF MURDERING MY WIFE, and his website opens with the statement:

You may know me through the impending court case in which I will be prosecuted on the charge of murdering my wife, Suzy Moulton, whom I assisted to die when she was in the last stages of her terminal agony. The proper term for this is “mercy killing.” It is certainly not “murder,” with which I have been charged. I regard my final intervention, to hasten her death, as an act of love, and morally just. I would wish to be treated similarly.

I don’t know if this defense of assisted dying would cause a storm in today’s social media world — it does in the novel — but I’ll bet it is now less contentious than saying that a female is a person with a vagina.

If you had to choose to live in a different historical period, which era would you choose?

Toothache, migraines, gout, childbirth, dying in agony, polio, smallpox, infant mortality… Pain! However privileged in other ways, I wouldn’t wish to live in an era before anesthetics and antibiotics. A rich life in Georgian England, or in the glory days of the Hellenic period? No thanks, too easily disrupted: pain displaces pleasure in a trice. Alas, it doesn’t work the other way round.

This makes me unapologetically modern. My generation of privileged persons from the wealthy world — born just after the War — has had much relief from agony and contagion (until now), avoided catastrophic wars, traveled cheaply and in comfort to see the world. I’m hardly an intrepid traveler, but I have visited over 50 countries. We eat well, drink well, and by and large sleep well. We have access to so many delightful and improving experiences. Until recently we didn’t have to worry about the physical well-being of our children.

And it’s all over, those halcyon days. Finished. Never to return. I’ve been lucky, and don’t wish to be transported anywhere else. Especially into the future.

Echoes of Kafka and Lewis Carroll are also palpable in Darke Matter. Could you comment on their importance to you as a writer?

I have loved both since I was, what, 16? They have in common an underlying sense not of absurdity, a term I dislike, but that the world could so easily, and dangerously, be other than it is, its laws and procedures suddenly overturned. I am constantly indebted to both The Trial (which features in James Darke’s journals) and Metamorphosis. I adore Alice — who had seen a cat without a smile but never a smile without a cat — and the Walrus and Carpenter:

O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!

He chortled in his joy.

I’d go to bed smiling for a year if I’d written those lines.

Darke Matter offers glimpses of the fantastic and the absurd in the margins. Do you think you will ever write a magic realist novel?

I’d rather die first. In fact, I will.

There’s enough to discover in what we think we know, without fiddling about inventing absurdities (a useful term). I cannot think of a single work of “magic realism” that I unequivocally admire. It’s an oxymoron, and should stay that way.

James Darke’s wife Suzy was a novelist who gained some acclaim and yet Darke is critical of her brand of realism. Is this a not-so-covert criticism of the current over-dependence on facts in the novel?

I rather admire writers — Nicholson Baker, Updike, and many others — who are comprehensively attentive to, well… everything. There is a passage in Rabbit at Rest in which there’s a full-page description of eating a macadamia nut. I couldn’t get beyond salty and a bit mushy.

Suzy Moulton was obsessed by recording detail, making the readers — in Conrad’s injunction — making them see. James hates all this, finds it obsessional and dull. If you want to convey a walk in the park, take a fucking camera: images are more accurate than words! What he prefers is a novel replete with ideas, striking images, and original thoughts. Wide-ranging, ambitious, allusive, embedded in literary discourse. Not realistic, real.

But of course he is no novelist, he knows that. That’s part of the fun.

Finally, could you describe your process so that readers have some idea of how and where you work?

I need constantly to resist my fantasy image of how I ought to write — arrive at my desk early, sit for hours until lunch composing, eat something and have a walk, go back for more. End of day, no less than a thousand words.

Instead I write anywhere, in bursts of from two to fifteen minutes, break to pace about, do emails, check the news and sports results, eat a pickle, play solitaire on my phone — during which I am neither wasting time nor thinking, but unconsciously processing, getting ready for the next bits. It has taken me some 50 years to understand and accept this eccentric mode of composition.

I get as much done as most writers, just differently. But I still feel faintly embarrassed to seem so sloppy and ill-disciplined.

¤

Rick Gekoski’s Darke Matter is available at Book Depository and Gekoski.com.