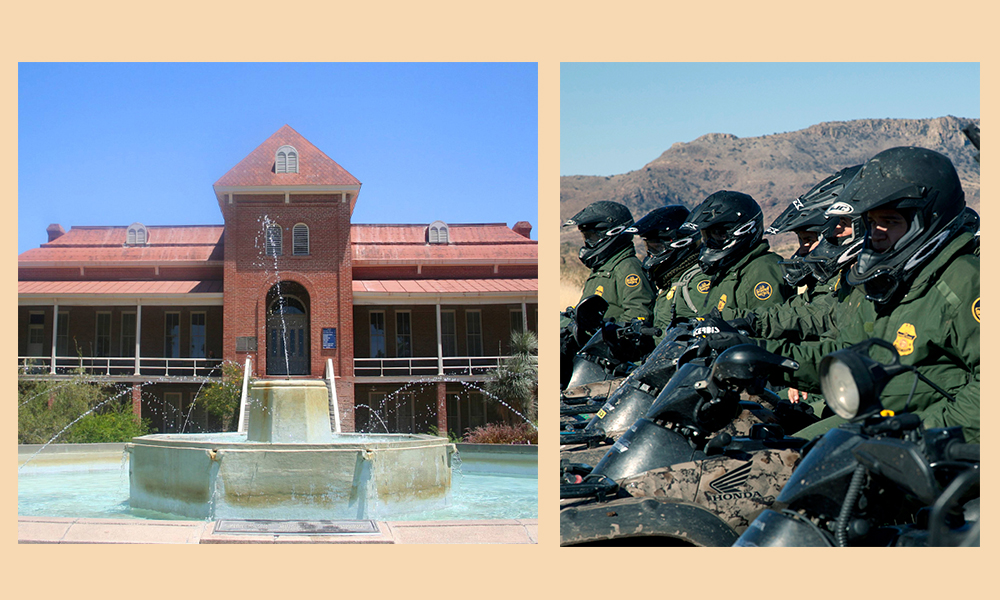

In mid-March, while teaching a University of Arizona English Department course called “Survey and Practice of Memoir,” I stepped out for a drink of water, to encounter a group of uniformed and armed Border Patrol officers in the hallway. In thirty years as a university professor, I have never seen uniformed officers in a classroom building except in response to a specific incident. Given the context of President Trump’s “border crisis” rhetoric and my university’s location fifty miles from Mexico, I assumed they were on campus to detain students whom they believed to be undocumented.

I retreated to my classroom, deciding that was the best way I could protect students who might be their target. If agents knocked at my classroom door, might I demand to see detention paperwork? Could I block the door? Should I resist or cooperate? The tension of the moment was heightened because I was teaching Auschwitz survivor Primo Levi’s The Periodic Table, devoted to his years as a chemistry student in northern Italy prior to World War II. Throughout the book Levi, an assimilated Jew whose ancestors had been forcibly evicted from Spain centuries earlier, self-interrogates: At what point in the years leading up to the war ought he to have realized that the men in uniform would be coming after him and his people?

Before long I heard protesters in the hallway, chanting slogans at the agents: “What did you do with the baby at the border?” along with curses in Spanish.

Days later I learned the agents had been invited by a criminal justice club which met in the room across the hall. After first issuing a statement defending the protesters’ right to free speech, the university president changed course, authorizing the university police to charge those demonstrators whom they could identify with criminal misdemeanors for disrupting an educational institution. Three demonstrators have been arrested, with the campus police committed to citing as many as they can identify.

As the teacher whose class was most directly affected, I was contacted by the campus police. My back-and-forth conversation with the detective revealed the vastness of the gap between my worldview and his. In his perspective, the law is an edifice handed down from a higher, race-neutral, class-neutral, gender-neutral authority, with his job being to enforce this “great system” — the phrase was his — of objective justice. Armed, uniformed police are a benevolent presence in our lives. In my view, rooted in my experiences as a gay elder, veteran of the LGBT civil rights struggle and AIDS era ACT-UP protests, the law is made by and for white, straight, prosperous men and a few white, straight, prosperous women as a means to protect and enhance their privilege. At any encounter with an armed officer in uniform, my instinct is to flee.

Indeed there had been disruption, I told the interrogating officer. It began with the appearance of armed officers in an officially designated gun-free space the university advertises as “safe” and “welcoming.” Given Border Patrol abuses and tensions among University of Arizona students, staff, faculty, and support personnel, I said, their appearance in a classroom building in uniform without advance notice showed poor judgment. They should have been sensitive to the impact of their appearing as a uniformed phalanx.

I argued for restraint. By definition mercy is a virtue reserved to the powerful. Rather than precipitate the embarrassing spectacle of a self-styled “Hispanic-serving university” using the law to punish young Latinas, why not respond to these young women’s rally with a reprimand and the formation of a faculty committee — oldest of bureaucratic ploys for defusing tension — to establish university policy governing the presence of Border Patrol officers on campus?

Restraint, however, is not currently much in favor. As of this writing, the university remains committed to prosecuting any demonstrators it can track down. President Robbins claims the matter is now out of his hands, though he has written the Border Patrol agents expressing his “appreciation” of their work.

At one point the officer told me, “I cannot imagine what it would be like to be an undocumented immigrant, but from my point of view, they’re breaking the law and my job is to arrest them.” This was a revelatory moment. My lifelong job description, as a teacher, has been to awaken my students’ imaginations, precisely so as to enable them to imagine what it is like to be someone else. As a novelist, I give much of my life to imagining what it is like to be someone else. My police detective, I realized, cannot afford to imagine himself into the lives of others, because doing so would so completely upend his understanding of his job.

Overcoming the gulf between our perspectives strikes me as essential to any kind of constructive dialogue in the coming election, but I see little evidence of that coming about.

That we have a Constitution guaranteeing freedom of speech is because of men and women who did not act with decorum and good manners. That people of color are not slaves, that they and women can vote and participate fully in society is because of men and women who, to invoke the university president’s term, “disrupted” business as usual. That AIDS is a manageable disease is because of brave men and women activists who did not act with the decorum and good manners advocated by the president of the University of Arizona.

On the day of the confrontation, in the context of The Periodic Table, my lecture and discussion notes seemed at once irrelevant and more on the mark than I could coherently discuss. “What we call chance,” says the Mother Superior in Dialogue of the Carmelites, “is only the logic of God.” We live at a moment when US society is more militarized than at any point in my memory; maybe more than at any point in its history. Do we suppose that the great majority of the men and women who carried out orders under National Socialism were depraved monsters? No, they were our fathers and mothers and siblings and friends and us, people who had been given a job to perform and for whom the job represented food on the table, a roof overhead, dreams for the future. I return to the questions Levi posed in his memoir, now with more urgency: At what point should we begin asking when their orders will require them to come after us?

Novelist and essayist Fenton Johnson is on the creative writing faculty at the University of Arizona. His next book, At the Center of All Beauty: Solitude and the Creative Life, is forthcoming from W.W. Norton.