To the memory of Kevin Starr

There is no place in the United States more exciting than this campus …There is no place or institution offering more varied experiences; there is nothing like Berkeley.

-Daily Californian, 1965

The Walpurgis Night that welcomed the newlyweds to Berkeley in June 1968 was a surreal rite-of-passage. Literally, since we drove through three barricaded checkpoints to get to our sight unseen apartment in the South Campus. The repeated stop-and-search by California Highway Patrolmen in helmets and flak jackets was unnerving enough, but a trashed Telegraph Avenue — a phantasmagoric sight in the police strobes — was a rude awakening, a lurid preview of the insurrection to come. Our baptism of fire. Too late to return to La Jolla. The whorls of teargas told us we were in for it.

The Berkeley I thought to attend had already graduated. The Vietnam Commencement in May meant the page had been turned. The War had come home and become superannuated, what more to say, antiwar outrage morphing into amorphous grievance, combative stances and militant posturing. Enter the non-negotiable demand and the stentorian urgency of On Strike Shut It Down!

The we-shall-overcome decorum of FSM (Free Speech Movement) had been rudely elbowed aside by the changing of the guard, exeunt the solemn coat-and-tie procession through Sather Gate. Shot in vintage black and white, suitable for eventual Free Speech Movement Café display. See instead the riot footage in graphic color, of hardcore militants in army fatigue jackets mixing it up with the advancing police line. Cue the clenched-fist bromide Power To The People!. For the two years of that Long 1968 — from Telegraph Avenue to Cambodia Spring — Berkeley witnessed a power struggle of no little sound and fury. And no little significance for the destiny of Ronald Reagan.

Indeed it is safe to say that in those state-of-siege years higher education in California got turned on its head, lost its head, got transvalued, but not in the ways the Paris-inspired enrages hoped or anticipated. All power to the paroxysm. The Plateglass Revolution devoured its own, but not before defiling the idea — the necessary ideal — of the University. To this prole growing up across the Bay in San Francisco the Campanile represented the pinnacle of the life of the mind, Fiat Lux. Enlightenment. Liberation from the idols of the tribe. Not the nadir of mindless action. Ensorcellment. Domination by the idols of vox populi theater.

The world’s greatest university — ranked above Harvard, ranked above Oxbridge, ranked above its money power (The Regents) design and mendicant (The Governor) subservience — was not just another knowledge factory, punch your timecard, but a cynosure of humanity at its brightest and best. And most revolted and impassioned. Mario Savio had done the institution proud. I did not need a tutorial in wealth and privilege to know who used to attend Phoebe Hearst’s favorite citadel of learning, or what lucrative quid-pro-quo that entailed as an Old Blue. The Cal status game and the Berkeley status quo were untenable and even — at Lawrence Livermore, the Soviet City Of Science that Edward Teller built — unconscionable. The University had a lot to answer for, going back to The Bomb.

But the gadarene rush to Pigs Off Campus! and the bandolier bravado of By Any Means Necessary! preempted that necessary inquiry, debased it, turned it into agit-prop boilerplate, bear-baiting, bivouacs and shotguns and bayonets. And teargas. Lots of that. Introducing CS gas by helicopter. Which found my wife and infant son trapped on the bayonet encircled campus during the height of People’s Park.

Because — lucky us — our Dwight Way apartment was half a block from the embattled site my wife had fled the CN fog guns to the relative peace of Strawberry Canyon. The infamous Guard helicopter spewing CS passed directly over her just as she thought the coast clear to return. At the same time as I was being witness to the digital wrath of the Governor Of California, a lathered Ronald Reagan in the flesh, not ten feet away giving me and a few other stunned passers-by the finger (having ensured that it wouldn’t be photographed — O to have had a cell phone then — by ushering the press inside the rear of University Hall, where an emergency meeting of the Regents was convening, then rushing outside solo to express high dudgeon in classic Berkeley militant style), my wife and son were vomiting from the release. My son has been afflicted with respiratory problems ever since. The middle finger has been raised to honor The Gasser — “If it takes a bloodbath” — every People’s Park anniversary since.

¤

I was a harried undergrad, subsisting on the GI Bill, avoiding the Revolution like the plague but becoming “politicized” all the same, thank god for Veterans For Peace, fascinated — and appalled with my fascination — with the battle royals that swept through Sproul Plaza and onto Telegraph with the regularity of media events, especially virulent in spring, when the fog-shroud of the quiet morning lifted just in time for another solar-powered go-around with the forces of repression. This Revolution was televised against the backdrop of blue skies and golden haze, a surfeit of ignoble deceptions and ignominious self-deceptions: take that Minerva.

In those years of street-fighting man, of bandannaed crazies and black panthers and blue meanies and CHAOS provocateurs and the more-militant-than-thou, of incendiary rhetoric and the non-negotiable demand and the martial bellow the Administration hunkered in the Sproul Hall basement, the Faculty climbed the ivory tower all the way to the Olympian heights of Grizzly Peak Boulevard, and the Student Body braved the South Campus Combat Zone to pursue an education riddled with fugitive classes and rump semesters. The university is shut down by the order of the Governor. Hence the only academic procession I ever witnessed — tear gas mortars instead of mortarboards — was the long line of California Highway Patrol cars sweeping onto campus, a daily sight during the interminable and increasingly ugly Third World Liberation Front Strike.

Pace TWLF, the close order drill of the Black Panther Party was something to behold. Power to berate came out of the mouths of the bereted ones. Agit-prop was the lingua franca of the Long 1968, and no radical rhetorician came close to the hectoring homilies of an Eldridge Cleaver or the inspired histrionics of Huey P. Newton. All Power To The People. All Power To Black People. Careful to make their exit before the shit hit the fan, the Panthers had the white audience hanging on every incendiary phrase. The Ten Point Program Of The Black Panther Party — no black nationalism for them — was duly recited in the Newton sing-song falsetto, Dig!, backed by the glowering Panther phalanx, Right On!, but the Cleaver refrain of Off The Pig! got the crowd really going, jeering call and thunderous response, until it was ready to take to the streets and take it to the Pig.

Proving one’s militant bona fides was the name of the blood sport as the tear gas canisters flew and the cannonades of plateglass shattering meant the battle was joined. Over Cambodia, over ROTC, over the Park, over the Third World College, over Eldridge Cleaver, over Solidarity with the French Students (where we came in that Sunday night in June). There were no shortage of causus belli, no shortage of Up Against The Wall beardings, not when time, place and manner were invitations to a beheading — as well summon in loco parentis — and the Administration vacillated between the hard-line ordained by the Governor and placating the implacable ones. The sorry history of People’s Park case in point.

Consciousness raising and conscience lowering worked hand in glove to ensure that the hors d’combat — the crowd working itself up into a martial frenzy with ulullating war-cries — was about as intense as could be found this side of the Democratic Convention in Chicago. What is truly remarkable is just how few casualties there were given the ferocity of the street battles. The much feared Blue Meanies, beefy Alameda County Sheriffs wearing blue jumpsuits and brutality on their rolled-up sleeves, killed one and blinded another, and though they counted coup with their outsized cudgels, who knows how many skulls were fractured, they were still reluctant to go all the way to the Reagan — “if that’s what it takes” — bloodbath scenario.

One morning at the height of the anti-ROTC campaign the campus was turned into Police Day, as contingents from virtually every Bay Area jurisdiction marched to and fro in full riot gear. The sound of four foot cudgels hitting the pavement in lockstep unison is one never to forget. Needless to say the NROTC building was spared the day of reckoning. Overall The Massacre Of Berkeley was averted, but barely, call it white skin privilege stretched to the breaking point, and the fact the California National Guard, with bayonets fixed for crowd control, did not lock-and-load like their counterparts in Ohio has to reckon a minor miracle.

¤

If On Strike Shut It Down! resounds in the cranial cavity to this day, the fact is that for the bulk of the time the University soldiered on, classes were held, midterms and finals given, degrees conferred (but no commencement exercises were held in the Greek Theater during the three years I was a student). The College Of Letters And Science bore the brunt of the Berkeley Wars since its buildings were just on the other side of Sather Gate from Sproul Plaza. Hence Wheeler Hall auditorium had been torched, Doe Library survived a fire-bombing, Moses Hall had been trashed, and Dwinelle Hall suffered any number of stink bomb releases, repeatedly clearing the building. The olfactory assault lingered for days on end, and to this day the slightest reminder of that horrid odor is enough to trigger utter revulsion. Defilement 101. We all aced that class.

If you lived on the Northside or were enrolled in the College Of Engineering and never had to venture past the Campanile (Physics, Chemistry, Math) you could stay out of harm’s way and proceed with business as usual, watching what went down in the Plaza on the local news at Six. Only once was the affluent Northside engulfed in combat, during Cambodia Spring, and only for a few hours. For most of the 28,000 students — the great silent majority — the Revolution was something to be avoided if at all possible, one more obstacle in the path to the diploma. Unless you found yourself somehow in the line of fire, and experienced a truncheon conversion, you were free to write off the travail of the University as an affront to your peace of mind and personal security. Later on you could claim bragging rights, you were there at Berkeley In The Sixties.

While some two to three thousand students and street people were caught up in the Plateglass Revolution the other 25,000 or so found it anathema, and kept their distance. Business as if usual. Unless classes were suspended or cancelled outright the Schools and Departments could continue to transfer knowledge. In effect the GSM turned the University into a knowledge factory. The worst fears of FSM were realized, ironically, not by much maligned liberal administrators like defenestrated UC President Clark Kerr or feckless Berkeley Chancellor Roger Heyns but by the student body itself. Precisely in not facing down the defilers, in not coming to the defense of the University, the students delivered the University over to the money power. The Plateglass Revolution begot the Reagan Revolution.

The one student organization that had the clout to do just that, to save the University from itself, to shutdown the Revolution and send the defilers packing never did assert its authority. It came close. During the anti-ROTC campaign it showed it had the firepower to work its will. The Administration, which had long lost all authority, and respect, looked to it to save the day, and it did on one memorable occasion, heading-off a planned march to torch the NROTC building. The militants were not pleased. The debate inside the Student Union instead could have been the turning point, the return to sanity and civility, to the scorned ideals of FSM given voice by Vietnam combat veterans, had not Nixon decided to invade Cambodia.

Ironically the War returned to Berkeley, a veritable fuel-air explosive across the nation’s campuses, aborting the Ivory Tower rescue mission. The convocation, in the Greek Theater, was a throwback to 1964. This time On Strike Shut It Down was voiced by the student body as a whole, and supported by the faculty, who “offshored” their classes. Pedagogy continued at any number of off-campus sites, including the Newman Center at Dwight and College, where the History Department saw a heated debate between the young turks and the old guard about the future of the profession. But the heady solidarity amongst the strikers soon became the same old, venting in the street, taking it to the Pig, baiting the bear, one last encore of street-fighting man.

For a week the campus saw pitched battles, of an intensity that easily matched the worst of People’s Park or the TWLF Strike. Indeed, this was the climax of all that had gone before, a valedictory paroxysm. But then one fine May day it was over. Call it Cambodia Commencement Day. The Governor shut-down the campus and dispatched the Guard to enforce the edict. He had his make-my-day victory. Berkeley In The Sixties was over. It had served the Governor’s purpose. The University would be a defaced, damaged thing, the Campanile a symbol of capitulation. I couldn’t bear to look at it. I kept seeing Reagan’s truculent face on the clockfaces giving us all the finger.

¤

In May 1970 the UC Berkeley chapter of Veterans For Peace convened at the Pacific School Of Religion. The view from atop Le Conte was spectacular, San Francisco and the Golden Gate Bridge commanding the sightlines. A salutary reminder that there was a bigger world than the besieged confines of the University, which by then was under Guard lockdown. For three days we conducted our own Vietnam Commencement. We listened to academics, we listened to activists, we listened to our own strong inclinations to do something dramatic. But aside from placing medals and campaign ribbons in a large jar and dispatching it to the White House we elected instead to go our separate ways. Nixon had been thwarted once again, thanks to Kent State and Cambodia Spring. The page had been turned. The American War would soon be over. The Sixties were history. We could go back to the rest of our lives. Demobbed take two.

During the Long 1968 Veterans For Peace had sought to keep Vietnam front and center on the Berkeley campus. After all, some of the earliest demonstrations against the War — stopping the troop trains in 1965 — had a Berkeley gestation. But aside from the Big Marches in San Francisco in October and November 1969, the War did not figure in the remit of Power To The People. Even the anti-ROTC campaign had a target-of-opportunity feel to it. A placeholder between People’s Park and Cambodia Spring.

For those of us who showed up one night in Dwinelle to establish a campus chapter, the personal was the political. And vice-versa. Shook Over Hell. Not PTSD. The War had come home all right, a head count of those who had been In Country, and making one’s peace with it meant going to war with it — and with the Plateglass Revolution, which consumed the oxygen on campus. A two-front war as it were. Because most of us were married, and carrying full loads, there could only be sporadic efforts to retrieve Vietnam from the dustbin of Berkeley history. There were the marches in San Francisco, the actions, most notably at the Oakland Induction Center, and there were the panels and discussions, most notably the debate with NROTC students.

Mostly there was the band of brothers, at most fifty or so active, who wore the uniform of the antiwar veteran, and whose authority, a weasel word otherwise, could not be challenged, not by the Administration, which went out of its way to accommodate us, and not by the Revolutionaries, who couldn’t think to avoid us. We were The Big Men On Campus during the Long 1968, and the fact that some 900 veterans were attending UC on the GI Bill meant we could have shut down the Revolution at any juncture. Even People’s Park. The power was there, in the Plaza as it were, waiting to be asserted, begging to be asserted, demanding to be asserted. Too bad we didn’t think to wield it until it was too late. Even the Governor, who battened on the defilement of a great University, would have had to accede to our intervention. The sound and fury won out, and the Governor went on to fulfill his destiny.

¤

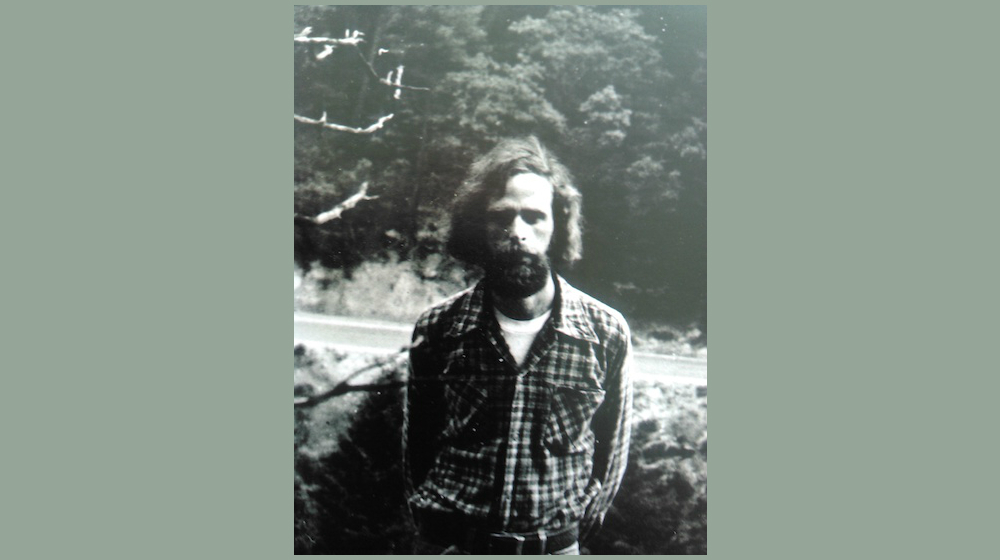

I found had matriculated in the curriculum of defiance and despair. I wore my defiance on my sleeve, the peacoat with the chevron still attached, gangway Che and Mao, and my saturnine countenance betrayed my what-am-I-doing-here despair. As well as a spouse and father I was now a Science Student For Social Responsibility and a Veteran For Peace, The Bomb and The War paramount, now one now the other at the forefront of foreboding consciousness. Later I would add The Holocaust (a term just coming into use) to the weight of the world on my shoulders. The Berkeley Tripos as it were. Read Raul Hilberg and truly despair; read Primo Levi and become defiant again.

As a physics major The Bomb became the focus of morbid preoccupation. The Physics Department was radioactive, half the faculty had come of age at Los Alamos. The photos of the famous men on the department wall — Nobel Laureates and National Academy Of Sciences — put the fear of god in you — good luck measuring up to their eminence — but then JASON and Lawrence Livermore told you the devil had a hand in the department as well, kept under wraps of course. Hence the repeated drive out to Livermore, to confront the nuclear weapons designers at their irenic enclave, an incursion into the true heart of human darkness. Fiat Lux inside a black hole.

More than a little light escaped those encounters. Absolute evil — the destruction of humankind — was joined at the hip with ultimate good — the elimination of total war, a double bind with a double casuist twist that Kafka had fashioned to confound Kant. The future of the world couldn’t be separated from its obliteration, a suicide vest all wore, wired to the countdown of the Doomsday Clock, the latest model turned out by the ingenious artificers of Lawrence Livermore. The highest reaches of high-tech. No expense spared in achieving the ne plus ultra. Absolute zero. The abyss.

Deterrence was no abstraction to those who labored under its anodyne mantle to manufacture the abyss. It put food on the table and sent their kids to school. It brought professional challenge and achievement. Intramural competition with Los Alamos, still part of the UC domain. Intense competition with the USSR’s City of Science. Above all it gave moral sanction to the work. It got you through the workday sanity preserved. Saving the world by making MAD even more state-of-the-art. Overkill 101.

The mind-bending theodicy made everyone I met at Livermore sane. Perhaps too much so. Cue the Rod Serling. Indeed the suburban homes that welcomed the radicals from Berkeley were out of a Twilight Zone episode. Was it always 1958 here? One entered prepared to proselytize and ended the evening impressed with the soul searching. It took some courage to even show one’s face. The Lab was watching. Aside from Lowell Wood, Teller’s protégé, who baited the bearded one, the assembled were engaging and thoughtful, and one felt awkward presuming to convert the heathen. Reason spoken here. They more than most had to think the unthinkable, to perform a Pascalian wager. They had made their peace with The Bomb. Peace was their profession, and no amount of moral opprobrium visited from Berkeley would change that. Still the undercurrent of unease was there. Enough protest had been held at the Gate to tell them what the Left Coast thought of their work. Solitary confinement, no matter how idyllic, begins to chafe, and denizens of LL longed for UC legitimacy. Intellectual exchanges with Berkeley. The Governor’s idea of a University, Lawrence Livermore served as a cynosure of true faith and allegiance. The ultimate ivory tower. Ala Kafka an inverted campanile. All the way to the Nevada Test Site. Fiat Noir. The anti-Berkeley.

¤

The idea of a University is a nebulous thing given intransigent flesh and bone by a faculty ready to defend it. Against loyalty oaths. Against Cal somnolence and Old Blue recrimination. Against the wrath of the Governor. Against snaking lines of students wielding baseball bats, tripping fire alarms and bellowing On Strike Shut It Down. The invasion of a classroom in the bowels of Dwinelle during the TWLF Strike was stopped in its tracks by a diminutive professor who refused to budge, much less vacate the room. It was the gutsiest move I witnessed at UC. He would not be intimidated. He would not surrender his classroom. He stared down the vehement ones with unyielding resolve. Valor. The bantam had grown to heroic stature. American diplomatic history would never look the same. He would later be denied tenure.

The great accelerator that was The Sixties turned the eternal verities into ephemera before smashing them into each other. Truth, Beauty and The Good now had half-lives measured in units of relevance. And so did we. The half-life I devoted to my studies during the Long 1968 was one that drove my physics advisor to exasperation. “Are you sure you want to be in this department?”

My class lists included everything but physics. I figured to cram the technical stuff while casting as wide a net as possible. Tout l’azimuth. Hence the roll-call of professors in my three years taking or auditing classes attests to the glory of a Berkeley education. Not for nothing did it rank in the academic empyrean. Those teachers included Leon Litwack, Fred Wakeman Jr, Carl Schorske, Sheldon Wolin, Paul Feyerabend, Hubert Dreyfus, Richard Webster, Martin Malia, Daniel Lev, Franz Schurmann, Johann Snapper, Michael Rogin, Nelson Polsby and a host of others, not to mention Charles Schwartz, gadfly extraordinaire, who taught a generation of physics students what it meant to be a “radical and rebel” (Bohr) in the cause of human betterment. The Szilard Prize is long overdue. Too, Hannah Arendt and Noam Chomsky provided inspiration from afar, what it meant to be a public intellectual, and I read them avidly.

Exemplars who soldiered on notwithstanding the assault on the life of the mind that was Berkeley in the Long 1968. The Morrison Reading Room in Doe Library, with its faux British Club décor, was my refuge from the political storm, and its armchairs afforded the start of my writing career, as I discovered the periodicals, the New York Review most of all, engrossed in the brilliance of the prose and the force of argument. Behind my back I was being recruited CIA style. I too wanted to become a public intellectual. A generalist. A writer.

There was no commencement exercise for the Class of 1971. Affinity groups instead held low profile ceremonies of relief. Tears not from gas. The Long 1968 had taken its toll. A transcript riddled with buckshot and reeking of tear gas, a diploma stuck on the end of a bayonet, a degree conferred by a Governor giving you the finger. Who would credit such a rite-of-passage, much less eulogize it. Enough to walk away in one piece.

A few months before, in March, we stole a march on that stealth exeunt, and exited Berkeley in the early evening, back to La Jolla. Symmetry coming and going. Our rite-of-passage was marked by another Walpurgis Night. In the Newhall Pass the Golden State Freeway was a debris-field, eerie in the moonlight of the early morning hours. The earthquake that had felled the Golden State had struck the San Fernando Valley the day before. The sole vehicle negotiating the circuitous detour that 3AM hour, the U-Haul passed a phantasmagoric sight of destruction. Collapsed overpasses. Cantilevered roadway. One look told us we were in for it. The personal was at the mercy of forces the political couldn’t fathom.

¤

The famous New York writer shook her head, incredulous that so beautiful and serene a campus as the University of California should ever have witnessed the worst of the Sixties. Clearly the Berkeley she had in mind was the Berkeley of Alice Waters and Mario Savio, not the Berkeley of OFF THE PIG. How was it possible, she sighed, for students to engineer the trashing of an enclave this enchanting, this sublime? It was one of those spellbinding evenings that the Athens of the West reserves for visitors from the East, and as the group of eminent literati ogled the storied battleground I could only think to answer with the University motto. Fiat Lux.

The University bound up its wounds as best it could, namely by living down its reputation as the citadel of the New Left. Power restored to the elite. Tenure as payback. The Campanile had not come crashing down, Doe Library had survived its fire, and Sproul Plaza resumed its scruffy operation, high noon no longer featuring the amplified causus belli. Minerva no longer had to worry about taking flight. Let in the sunshine. The crazies of Berzerkley decamped to a vault in the Pacific Film Archive. The University, survived, barely, and during the ’70s was a diminished thing, a campus reeling from post traumatic stress, the return of normalcy affording a kind of demobbed convalescence for the Berkeley War weary. Fiat lux indeed.

The Revolution had moved from Politics to the Psyche… from street fighting man to women taking charge, the feminist and New Age movements, and once again Berkeley found itself in the vanguard, ground zero for the triumph of the therapeutic, let a thousand and one nostrums flourish, everything from est and pre-orgasmic to local produce and Peet’s Coffee (where my ex worked). The center of gravity had shifted from the South Campus to the Northside, from the plateglass of Telegraph Avenue to the glassware of Chez Panisse and the rough-hewn, weathered look of Sea-Ranch knockoff Walnut Square.

Atop the Square there was a small espresso cafe, with an outdoor deck boasting a superb view of the Golden Gate Bridge, and I spent many an hour there on a caffeine high, surrounded by the gentry of a rapidly gentrifying Berkeley, professors and therapists and wisdom seekers — be all that you can be thanks to extensive “training” — even a few writers and journalists. I had to listen to a plump woman prattle on about a book she had just submitted, about a vampire named Lestat. Good luck to her. The bloodbath that Reagan had once promised Berkeley had turned into a roseate glow bathed in prosperity and the unabashed promotion of the good life, the salubrious clime and the harkening Hills making the Northside the epitome of the California Dream, it didn’t get much better than this if Food and Drink and Inner Peace was your thing.

¤

There is no Long Power to the People Café. No Eldridge Cleaver steps. No place to display the baseball bats used to enforce the TWLF strike. No blown-up photos of the Blue Meanies, or the Panthers, or the Guard Helicopter. Certainly no photo of Ronald Reagan giving the finger from the rear of University Hall. The Free Speech Movement is the official memory of Berkeley in the 1960s. The Mario Savio steps and the Free Speech Movement Café recall the University at its zenith, its Minervan apotheosis — when the campanile soared into the scholarly empyrean and the campus could fairly lay claim to being the best in the world, certainly among the most beautiful. I missed that heady experience. The campus was not beautiful when I was there.

Rather the University I suffered was under siege, hunker down, too often gas wreathed, undergoing a defilement that was a joint project of the Governor and the militants. His minions who unwittingly staged the Long 1968 for his benefit. Understandable why the University would want to expunge that memory hole.

The siege is back, and the legacy of FSM is being defiled by the epigoni of Ronald Reagan, who have “weaponized” Free Speech in order to make it a mockery. Turn it on its head in order to flaunt their contempt for the Mario Savios of this world. Vile speech, the more vituperative and slanderous and racist the better, where better to declaim it than in the one institution that made freedom of speech a noble cause and lasting memory, a bending of the arc toward social justice — the one great university in America that still exemplifies dedication to the public good.

How brave of these chaos provocateurs to come into the belly of the beast and count coup for the entertainment of their social media bros, amp up the jeering one-liners so the easily-baited Antifa and their puerile Black Bloc will do their salivating thing, the whole world watching as Berkeley once again reenacts the Long 1968, cue the truncheons and tear gas, the plateglass cannonading in the Student Union. I think of that diminutive professor holding his ground in Dwinelle and I want to retch as farce becomes tragedy. The Long 1968 casts a long shadow.

I know if I were an Iraq or Afghanistan veteran I’d be mighty pissed. Fought and died for this dungfest? I don’t know how many are attending UC on the GI Bill, but even an army of one is enough to inform the shock troops of the alt-right that they defile at their peril. This time around veterans have the University’s back.