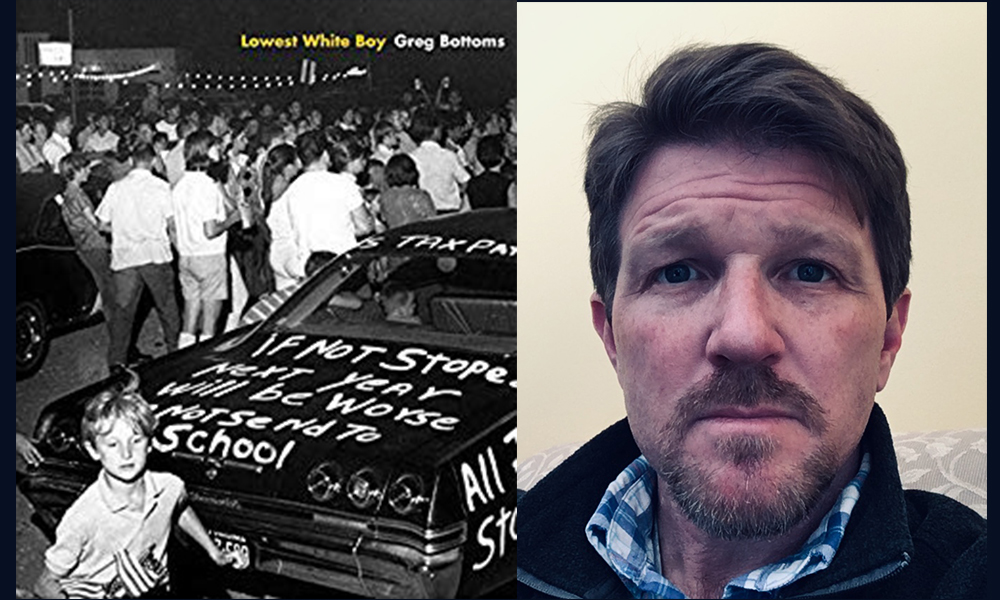

It is rare for a white man who grew up in the heart of the former confederate states to write a book that challenges the deep root of racism in the American South. But Greg Bottoms is a rare man. What follows is our conversation around his latest book, Lowest White Boy, a hybrid memoir/social critique, written as a series of short vignettes interspersed with imagery from the era of school desegregation in Virginia. Lowest White Boy was released by West Virginia University Press this month. The book takes its title from a quote attributed to Lyndon B. Johnson by Bill Moyers: “if you can convince the lowest white man he’s better than the best colored man, he won’t notice you’re picking his pocket.”

Bottoms is a professor of English at University of Vermont, where he teaches creative nonfiction. He is the author of many books, including Angelhead: My Brother’s Descent into Madness, The Colorful Apocalypse: Journeys in Outsider Art, and Spiritual American Trash: Portraits from the Margins of Art and Faith.

¤

AMY M. ALVAREZ: It’s rare for a white man who grew up in the South to investigate his own experiences with racism, classism, and sexism — as a resistor, but also as a perpetrator and bystander. What brought you to write a text that delves into these experiences?

GREG BOTTOMS: The memories in this book have a charged place in my personal psychology, so they are moments I needed to write about. The impetus for this writing — and writing it in this way, as an explicit mixing of autobiography, social interpretation, and what I guess I’d call imaginative documentary — has to do with our American moment, which is very dangerous, but it is also a kind of near-apotheosis of the darkest, most hateful and immoral strains in American society. I felt an urgency to try to demystify what white racism is — how it exists in complex layers that are harder and harder to see as they get away from individual experience and into social, political, historical, and ideological spheres.

Your mother seemed to have had a tremendous impact on your ideas about race and tolerance. She certainly practiced the ideas she preached, even driving a bus of black children during school integration in Virginia. Tell me more about your mother. What do you think allowed her to be both tolerant and kind in such an intolerant atmosphere?

I think she, like a lot of more progressive Christians, could see the unconscionable immorality at the heart of racism, even as the structures of racism were seemingly intractable and incomprehensibly big. She didn’t understand racism at a deep philosophical or historical level, of course, and racism as a constant reality in policy and law and attitudes was so powerful as to be hard to get one’s head around, especially in the South in the 1970s. But I really think that you cannot take to heart the teachings of the four gospels, as I believe she has, and be okay with American racism without just bubble-wrapping yourself in delusion and moral relativism.

One aspect of the book I enjoyed was your meta-commentary on your own writing process (“Put down what feels like the facts without literary fuss, maybe worry about style later,” you write on page 39). It felt as though you were delivering a master class imbedded within the text itself.

I started to do it in this way in drafts and then liked how that conveyed something about the fluid nature of writing and trying to communicate.

The historic black and white photos in Lowest White Boy are haunting, disturbing, and hopeful in turn. It seems that you often use images — whether photos or working with illustrators — in your books. I wondered whether this marriage of text and image might be an impulse from your past work as a journalist?

I’m sure it is to some extent. I’ve always loved journalism that has a muckraking feel, that wants to try to raise consciousness in the reader and document troubling American social realities. Images, to me, can layer and amplify a text in interesting ways. I’m also a very visual and narrative thinker.

Early in the book, you mention reading W. E. B. DuBois’ The Souls of Black Folk as a college student studying English and journalism and how this text “shook [you] ethically, morally, and spiritually.” As an English professor and as someone who has obvious concern for the ethics of our nation, what do you think the role of the humanities is in combating intolerance — especially racial intolerance?

The study of the humanities teaches students that the world is complex, people are complex, and that critical acumen is a key part of being a thoughtful citizen. Openness to new knowledge and learning as a habit of being seem so crucial to me now. Racial intolerance is dependent on ignorance. Imagine, for instance, a president who has never read a work of literature, never engaged with and thought about essential human feelings as they exist across cultures, never felt a tug of empathy or heartbreak for another, never experienced the complexity and richness of other and smarter minds as they convey the awe-inspiring texture of what it feels like to be alive in the world. Now THAT would be scary!

In the exquisitely written “Family Reunion, 1979,” you focus on the experience of refusing to hurl a racial slur at a group of young black men and an older man you thought might be their teacher, despite the threat of, and actual injury by, your cousin. Was this moment a personal turning point for you?

I think the reason the memory of that incident is so powerful for me has to do with how personal interaction with the minister/teacher disrupts racist ideology. The more people engage with one another across race, the more racist logic crumbles and looks like an absurd lens with which to view the world.

In addition to race, Lowest White Boy also investigates misogyny — especially misogyny that excuses itself using religion. In what ways do you think gender inequality plays into disenfranchisement of the “lowest white man?”

Johnson’s quote to Bill Moyers shows the former president’s understanding that the prideful poor and working-class white man was living in layers and layers of myth about his power. These myths could be exploited by a conservative political elite beholden to big business and the rich that telegraphed a shared white, masculine dominance with the their voter — hey, we’re alike and in charge and in this together against them (people of color, liberal intellectuals, women, etc.) — while undertaking policies that hurt and further disenfranchised these white men. Polling data shows that little has changed. Trump, the NRA, conservative media, and so on need to characterize their opponents as “weak” and often “feminine.” “Pencil-neck” Adam Schiff, “Low-IQ” Maxine Waters, Elizabeth Warren as “Pocahontas,” Obama as “leading from behind” and an “apologist.” Listen to Trump’s refrains: Putin was “very strong” in his denials. A congressman who slams a reporter to the ground is a “tough cookie.” Every instance of rising nationalism has been built around expressions of masculine power, and racism is always the core to its consolidation and rise in the culture. There are “caravans” of “illegals” and “aliens” coming. The Democrats are “soft” on crime and want “open borders.” I could go on.

In “New Shoes, 1975,” you wrote about the experience of teasing a young black girl on the school bus your mother drove about her sneakers — which were bargain shoes and not the “it” sneakers of that year — after you were teased by older white boys in your neighborhood for not having the “right” shoes. I felt this moment deeply as I was teased for my Payless gym sneakers in junior high school. I remember begging my mom for the “it” shoe of that era: Reebok high-tops. This moment is one that many young people still experience. In many ways, because of social media, mobile technologies, and deepening income inequality, young people might even feel this more deeply than we did. In your opinion, how might our fetishization of commodities keep racist ideologies alive?

I don’t know if I have a good answer to that. On a very macro level, I think commodity fethishism, social media, celebrity, and the inundation of information that are our consumer culture have stopped being distractions from more important and pressing reality and simply become reality itself for many. You can see, for instance, that the alt-right appeals to young white males online via the forms of contemporary viral advertising. That is an instance where the “commodity” being “fetishized” and exalted is white supremacy.

In several of the pieces, you address the “big lie theory” as it applies to the white perception of the African American community: the assumed violence of black boys, the assumption that poor whites do not have privilege because of their socioeconomic status, and the idea that black people having power or bravery is anomalous. These ideas obviously have horrible repercussions and persist in modern American society. As you mention at the end of the book, there is “a normalization of more explicitly racist commentary in what are considered mainstream conservative radio and television outlets.” What are the most important things that can be done to minimize harm and reverse these false scripts?

I think people of conscience, who are the actual majority, need to win and keep winning. Elections have consequences, needless to say. To the school board. To local districts. To counties and states and up to the national level. Representation matters. Who has power matters. Who tells the stories and what stories are told matters. Don’t expect everyone to operate honestly, by the rules, and in good faith. Call lies lies until you’re blue in the face. Don’t bring a butter knife to a nuclear war.

Amy M. Alvarez’s poetry is forthcoming or has been published in Sugar House Review, Rattle, The New Guard Review, and elsewhere. Her poem “Alternative Classroom Senryu” was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. She holds an MFA in poetry from the Stonecoast Program at the University of Southern Maine and is a VONA fellow. Originally from New York City, Amy currently resides Morgantown, WV and teaches at West Virginia University.