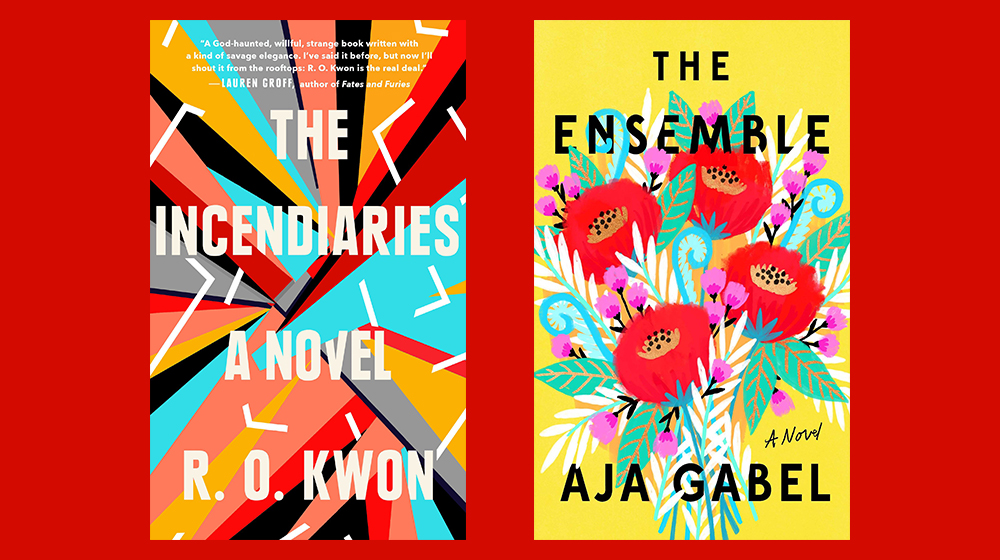

In a culture that frequently proclaims the “death” of symphony orchestras, opera companies, and conservatories, it is perhaps puzzling that two of this year’s most anticipated novels — Aja Gabel’s The Ensemble and R.O. Kwon’s The Incendiaries — place classical music at the center of their narratives. Gabel’s novel traces the path of the titular ensemble, the Van Ness Quartet, from its founding at a California conservatory, to its Carnegie Hall debut, to its residency at Juilliard. Music plays a less central, but no less significant, role in Kwon’s novel, in which the heroine-turned-cult-member Phoebe is haunted by her unrealized career as a concert pianist.

Of course, neither novel is simply about classical music. The most gripping moments of The Ensemble focus not on the musicians’ pressure-filled stage performances, nor on their contract negotiations, nor on their rehearsal routines, but rather on their interpersonal entanglements (artistic, filial, and sexual). The Incendiaries examines the overlaps between young love and religious fanaticism, exposing the gripping and perilous nature of both.

Yet, classical music grants Gabel and Kwon more than just an incidental backdrop or set of images. Both authors draw on the wide range of literary resources offered by classical music, with its ties to genius, competition, pressure, affect, and spectacle. What Gabel — a musician herself — calls the “webbed, collaborative endeavor” of chamber music provides a unique pressure-cooker for her characters to confront (often clashing) experiences of passion, commitment, loyalty, and collaboration. In Kwon’s novel, Phoebe’s pursuit of a classical music career is essential to her character — her ambition, her dedication, and her competitiveness. Most significant, though, is the way in which classical music gives Gabel and Kwon a way to explore intangible, often unexplainable moments of transcendence — of reaching beyond one’s here and now and accessing something ethereal and otherwise impossible to articulate.

Such metaphysical ideas about music are not new; 18th- and 19th-century philosophers and composers often espoused ideals of music as sublime and ethereal, apart from the material world. The German critic E.T.A. Hoffmann, for instance, wrote that music’s “sole subject is the infinite…music discloses to man an unknown realm, a world that has nothing in common with the external sensual world that surrounds him.” Such ideas retain their currency today, so much so that they veer on the cliché. A brief glance at the image site Pinterest reveals thousands of GIFs displaying quotations like “Music is my escape” or “Music is the voice of the angels.” We seem to be — and have long been — fascinated by music’s power to give us something else, something that we can barely verbalize but nonetheless yearn to experience.

In The Ensemble, the principal violinist Jana associates the Czech composer Antonín Dvořák’s String Quartet No. 12 (“American”) with “fall[ing] for the dream of a place, for a life that could be lived there, for something they were not but might be. It was about the shimmering itself, that almost visible stuff that hovered just above the hot pavement of your life.” For Jana, music is all imagined potential, set apart from concrete reality.

Kwon’s Phoebe also loses herself in her music. In one scene, she recollects how her preoccupation with a difficult piano piece by the fictional composer Libich distracted her from everyday social encounters, as when her mother tried to chat with her at the kitchen table: “I blinked, Libich vibrating in my head…I could tell she wished to talk, but I was lost in trills.” Phoebe’s playing, too, seems to disclose infinite, unknown realms; to her boyfriend Will, her music represents “God’s design made visible.”

And yet, both authors also indicate that such moments are ephemeral and even dangerous. Gabel continually reminds us that achieving musical brilliance requires not a loss of consciousness, but rather an excess of mental focus. Playing works by the Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich, we learn, “took an exhausting amount of concentration to pull the phrases together, to make the fragments and jumps compose a whole. You could not miss a millisecond in the piece.” The realities of the material world are never far from Gabel’s narrative; haunting the novel is the threat that the musicians’ careers — and thus lives — will be ruined by the very bodily pain required to achieve them. The violist Henry suffers from tendonitis in his bow arm; the second violinist Brit experiences recurrent infections of her “violin hickey” (the blister on her neck caused by friction from her chinrest); the cellist Daniel is plagued by a shoulder injury; and Jana is afflicted with a lower back injury for which she must see “doctors and spinal specialists and acupuncturists and chiropractors and massage therapists.” Gabel never lets us forget that for every “shimmering” musical moment, there are “bodies bearing the weight of their work.”

While Gabel exposes the myth of musical transcendence, Kwon reveals the perils of believing in it. Phoebe’s yearning for the sense of otherworldly glory that music once gave her renders her vulnerable to the Jijeh cult, which promises heavenly splendor but in reality coerces her to participate in violent acts. In this context, scenes that might have read as romantic evocations of musical devotion take on more sinister resonances. “[Libich’s] étude asked so much of me that, at times, I’d forget I had an I,” she says. “[P]laying had to be birthed in a place without an ego, in which I didn’t exist except as a living conduit, Libich’s medium.” Phoebe’s statement may seem to convey her self-sacrifice at the altar of high culture, yet, we soon learn that her loss of selfhood here prefigures something much darker: the erasure of her individuality when she joins Jijeh. Both musical training and cult membership require intense devotion and a willingness to be directed, even inhabited, by an outside force. Kwon thus refuses to align aesthetic devotion with any kind of ethical potential; Phoebe’s musical experiences do not uplift her soul, but rather leave her vulnerable to violent manipulation. The Ensemble and The Incendiaries thus both trouble Hoffmann-esque notions of music-as-transcendent. Fantasies of total escape are at best illusory, at worst dangerous.

Towards the end of The Ensemble, though, Gabel seems to hint at an alternative. The Van Ness Quartet performs Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 14 at a vigil after 9/11:

Jana thought they might spoil whatever magic they’d have at Carnegie with a free concert for a bunch of people in mourning…“It’s just music,” Brit said. “They just want music so it’s not quiet when people are crying.’” Which seemed to Jana like the worst reason in the world to play music. But as they played, with no one really listening, or not just listening but listening and paying tribute, or listening and weeping, or listening and praying, or listening and thinking, or listening and trying not to think, Jana saw that yes, it was just music, and that was perhaps its best attribute. It was art as part of the landscape, movable, livable art, and what these people needed was that, an apparatus of art to hold them up for a while.

In this moment, Gabel present an image of music as an art form fundamentally tied to community, healing, emotion, and deep (but profoundly conscious) thought. The most powerful music, then, is perhaps not “hovering above the hot pavement,” but on the ground, holding people up. While we might yearn for an aesthetics that allows us to transcend our current moment, we — and our art — must stay here.