In his “What Happens When You Treat Writing Like Acting,” Dan Bevacqua talks acting — a world he researched to write his first novel Molly Bit. Midway through drafting, Bevacqua took classes himself, a small group in a black box theatre in Northampton, Massachusetts. He describes the experience: “This early work was pre-language, which is where all language comes from, that terrorized place without an alphabet, where there’s only desire and fear, a pure art of the body, closest to the source.”

At this time, when the world is a terrorized place and the alphabet is scrambled, Bevacqua’s novel Molly Bit is a cutting — and capacious — view of calamity and celebrity culture. It’s the story of a fictional movie, her rise and her demise. In offering a rear-view mirror shot of the world we’ve created (that mad, grabby mess of glamour and lust and, yes, terror), Bevacqua challenges us to begin again, doing better.

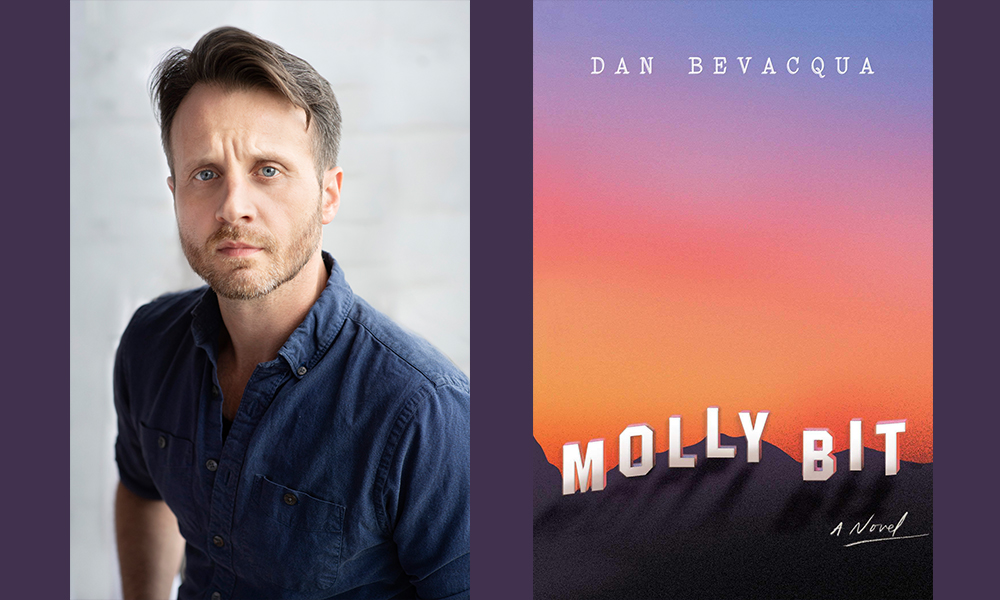

Dan Bevacqua’s first novel Molly Bit was published by Simon and Schuster in 2020. His short fiction and criticism have appeared in Electric Literature, the New Orleans Review, The New Inquiry, Words Without Borders, The Literary Review, and The Best American Mystery Stories. He is an Assistant Professor of English at Western New England University.

¤

JOANNA NOVAK: Molly Bit is a hard novel to describe. You could say the novel is about fame, or the life of an actress, but that’s only part of what happens and where the novel goes. What was your vision for the book?

I think Molly Bit is a novel that observes the arc of the late 20th century into the early 21st . It’s about fame, which has that weird consistency of illusion meets reality, but it’s also about the first “type” of person to be marketed and promoted through the use of screens — the movie star — and it observes her coming of age during a time in which all privacy is invaded; in which we’re each our own PR person; in which the words we say in public or on public platforms must either be benign or violently reactionary (or, the safest bet, total nonsense), so that we might then continue to exist in the world of popular culture, which seems to be the only place that matters anymore. Molly Bit is a novel that starts out all fun and games, and then it takes the reader inside actual America, into our own depravity and instinct for, among other things, femicide, racism, and misogyny. The book is also about a gifted actress — as well as obsession, ambition, friendship, addiction and recovery. In spite of how I’ve described the book, it’s also, hopefully, somehow, funny. Writing these answers during the Covid-19 pandemic makes me feel like none of them matter, and they don’t (compared to all who have died and will die and pretty much anything else), but the novel is, in addition to what I’ve said above, a time capsule of the years of national madness that directly precede, and make, our own.

When the novel opens, Molly is in art school; the reader sees her perform the lifecycle of a woman in three minutes for a Movement final. The novel’s structure — Life, Death, and Afterlife — echoes that early scene. What challenges did you encounter in structuring her life in such a deliberate way?

The whole book was a challenge, and one of the biggest challenges or frustrations I had to come to terms with was that, in order to write it the way it needed to be written, a lot of people would, as a result, react with shock or dismay. The second section, “Death,” had to exist. We are obsessed with murdered white women in this country. That’s not a sentence I enjoy writing down, but I believe it to be true. Women of all races and identifications are murdered all the time, of course, but in terms of our media (which is racist) — it’s a real death cult for some people. We live out a fair number of our days enthralled by narratives that are dependent up a reality of constant sexual violence, kidnapping and murder. And we can only manage to think about this phenomenon so far. We ask, whodunit? We ask, how does it feel for those who survive the victim? Maybe we ask, why did he do it? We don’t really ask: what is wrong with us — and not just in terms of our prurient viewing habits, but in real life? For me, as a writer, that was the real mystery worth solving, although it’s not much of a mystery, of course. To engage with the truth in any real way, I had to start before the beginning, and go beyond the end, and come back again.

Even when she’s reached the height of fame, Molly always seems in orbit. This seems to have much to do with the novel’s point-of-view — or, rather, points-of-view. Friends, assistants, neighbors, ex-boyfriends: the third-person limited inhabits all of them. How did point-of-view enrich the Molly you were able to portray?

Orbit is a good word. In many ways (and it’s maybe the single truly experimental aspect of the novel) Molly Bit isn’t quite there. She is, but she isn’t. The reader knows her just enough, but to know her too much would mean to destroy fame’s illusion. This was a demand the novel put on me. The task was to create a fictional famous person that actually seemed famous. The actor who was best at being famous in the second half of the 20th century was Jack Nicholson, because he understood the whole thing for what it was, and that to keep the fame going, and make it useful to him as an actor, all he had to do was not go on television. It helped that he had (has) the charisma of a thousand movie stars rolled into one, but he was smart enough to know that with that sort of power, all he had to do was go to the Oscars or a Lakers game, pop an eyebrow, and that was enough for six months. His absence, the mystery of who he was (and is — Jack’s whole disappearing act is part of it, no matter the reason) was part of the draw for audience members. He understood the interplay between absence and desire, and how that unknowingness, combined with the urge to pay attention to him when he did appear on-screen, helped people believe in his performances. The language of Molly’s interior life, of what the reader knows and doesn’t know about her, is dictated by similar constraints.

That being said, a novel needs characters, and not just a character who portrays other, more fictional characters. Having other characters with their own points of view in the book — and their own chapters — came out of that necessity, and its also helped to broaden the novel’s scope and intention. With Molly, I wanted to drop language down inside the image, but since the image despises language, and since any image will kill language like its infection, there had to be numerous characters to refract and see Molly through — and who, consequently, would then be seen. Characters like Abigail, Molly’s producing partner, and Marcus, her neighbor, exist in opposition to the stereotypes and clichés the world of the image (and I mean film, TV, social media, the inside of certain persons’ heads) makes them out to be.

Whether it’s a small detail like “she had hair pulled back into a wild pony,” or the ringing truism that “women make friends because their lives depend on it,” Molly Bit never falls prey to man-writing-woman syndrome. In what ways was creating that authenticity a part of your process?

For a long time, avoiding that syndrome you mentioned — which is real — was a big part of my process. I would imagine writers that I love, like Virginia Woolf or Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah, sitting in the room with me, and saying, “That’s bullshit,” until it got to the point where the paranoia I had about my failing, about writing female characters that would read like a 38-year-old straight white guy from Vermont had written them, made me sort of insane, and worse, had the opposite effect on the book, in that those female characters I’m describing were then devoid of unique traits that were specific to them, and so they became nobodies. My paranoia had turned them into clichés, and worst of all, advertisements. So I stopped caring, and assumed that certain readers (male or female; straight or gay or queer or trans; black or white or Hispanic or Latino or Asian; young or old; married to me or not) would like the book, and others wouldn’t, and I tried to be true to the characters, to who they were, and to how they would think and feel, and to what they might do in a given situation. This is the whole idea to begin with, of course, but the process did serve as a reminder that writing fiction is a serious moral act.

Speaking of authenticity: acting, Hollywood, the industry. How did you go about capturing that world? Did research inform the settings you worked with?

I did a lot research. I took an acting class, made various trips out to Los Angeles, and read all the Hollywood biographies I could get my hands on. Lithub published an essay about some of my research, but one of the aspects I wasn’t able to talk about at much length were the interviews I conducted. It’s strange. Like many people, I’m susceptible to celebrity culture. At the same time, I think it’s ridiculous and am repulsed by it (this, too, is common, I think). But no matter what, I take very seriously the people who devote their lives to making films. I admire them. It might be a selfish thing. Some of my closest friends work in the industry — these are people I love — and over the years I’ve known any number of talented actors, screenwriters and directors. In a strange way, loving these people helped with the tone of the book. My intention with Molly Bit’s tone was to bring the tragic farce of our reality into the language of realism. A world in which “[e]verybody wants to be famous” is not a sane world. That’s totally insane. But it’s also the world we all (myself included) participate and live in. Caring for lots of people who work in the industry helped to neutralize my judgment, and to create a fiction that mirrors a reality that has gone completely off its rocker. Our madness has much to do with the entertainment industry. The president is a TV ratings obsessed game show host whose ineptitude is killing us. That’s real. That’s what’s happening. How is that happening?

“She missed a time that never was, when everyone owned up to their broken hearts.” There are many times that never were over the course of Molly Bit: the book spans years and years, leaving much of life unseen. How do actors — and writers — channel nostalgia in their work? What draws you to this saudade?

Film is nostalgic, and since the book is in many ways about film, about the nature of it, Molly Bit was bound to think about nostalgia, and about how the characters engage with it. The very act of watching a film is bursting with a mood of nostalgia. You sit in the present tense and witness a fabricated memory of the past. Compared to the novel, it’s retrograde. Saying something like that comes partly out of the jealous competition I feel as a novelist toward filmmakers, which is silly, because they won a long time ago, but it’s also true. Films are nostalgic, and I love them in part for that particular mood they can create, along with the longing and desire they’re able to produce, or cool or melancholy, if you’re talking about Truffaut or Ozu, or total obliteration, as with Michael Bay. But no matter the sensation, and no matter the subject, all movies are about the lonely kid who’d rather sit in the dark than go outside. I guess I’m speaking about directors again — but that’s writers too, except we need more light. I sometimes think I write fiction because it’s a respectable excuse to give to people so they’ll leave me alone. I like people. As with anyone, I love certain people, but I’d rather be alone in my room, making stuff up, and writing makes that okay, and even encourages it. That’s not necessarily nostalgia, but it is longing, and a selfish longing for my own self, or at least the truest version of the world I can make with my own mind.

I think we’ll be reading novels that take up nostalgia as their theme for at least the next 50 years. First, the pandemic novels that are already being written, and then the real nostalgia novels, those written by the children of our generation, which will be about the emotional and environmental trauma they will inherit as the children of the last generation of people to remember the world.