And there won’t be snow in Africa this Christmas time

The greatest gift they’ll get this year is life (Oooh)

Where nothing ever grows, no rain or rivers flow

Do they know it’s Christmas time at all?”

— “Do They Know It’s Christmas,” Band Aid (1984)

Christmas as we know it today benefits from a surprising set of secular and non-Christian supports. As scholars of imperial print cultures, we are familiar with the ubiquity of the Christmas issue as a journalistic form but were nonetheless disoriented by the discovery of a Christmas issue of a colonial journal with Pan-Islamist leanings and a Muslim editor. Stranger still was the fact that this Pan-African and “Pan-Oriental” journal, The African Times and Orient Review, featured a Christmas issue for almost every year that it was in print. Confronted by a Muslim editor’s ecumenical deployment of the Christmas issue, we found ourselves reassessing its meanings as a form.

Historians of Christmas attribute the popularization of the Christmas tree as an English tradition to an 1848 supplement of the Illustrated London News which featured an image of a tree surrounded by the royal family. Thanks in part to the success of this issue and of Charles Dickens’ 1843 A Christmas Carol, Christmas annuals, gift books, editions, issues, and anthologies became an increasingly popular and much-anticipated yearly feature of British print culture; in this way, Christmas publications made “Victorian Christmas” a unifying cultural aesthetic as well as a symbol of Britishness widely disseminated along imperial circuits. Over time, the Christmas special was adapted to other media, including movies, television shows, and songs.

While Christmas stories and issues imagined Christmas as a family tradition shared by people across the nation, and thus helped to shape national identity, they had an important role to play in settler communities around the empire as well, where they gave those abroad a sense of connection to the metropole by virtue of their participation in the same rituals and customs, despite their disparate locations. British periodicals often published Christmas stories set in the colonies that emphasized these customs, and explicitly addressed readers abroad in editorials, using holiday sentimentality to emphasize bonds with friends and family back home. Mid-19th-century Christmas print culture thus helped to connect white settlers across the empire via religion, as well as race and national origin, while simultaneously making the signifiers of “Victorian Christmas” (plum pudding, a tree, carols, the hearth, Santa) globally recognizable and indelibly connected with whiteness — of the racial, as well as snowy, kind. By activating affective bonds between British and white settler subjects, Christmas periodicals prefigured the racist Greater Britain imaginary of the end of the century.

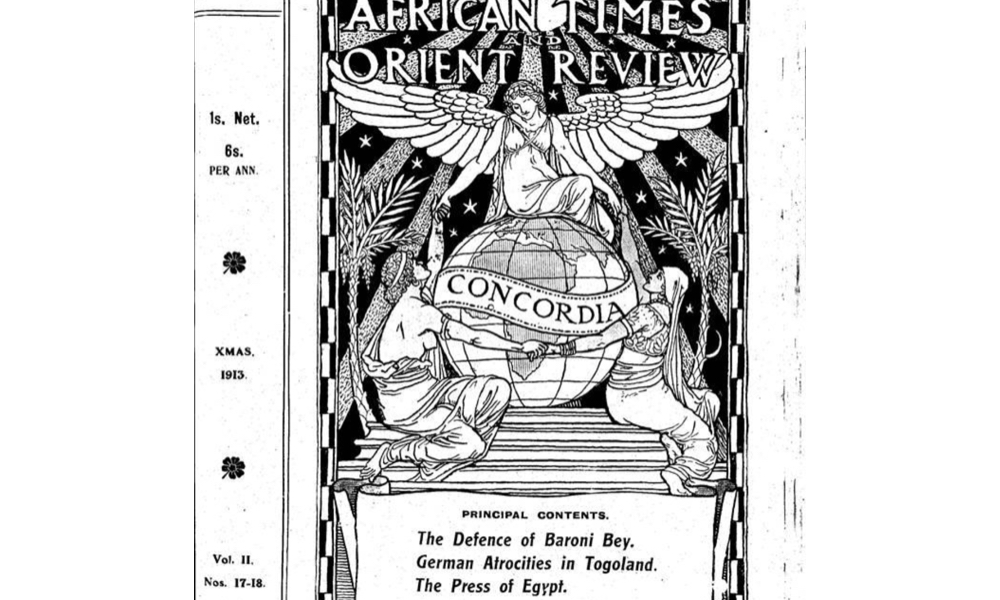

The African Times and Orient Review, subtitled “A Monthly Journal Devoted to the Interests of the Coloured Races of the World,” was founded and edited by Dusé Mohamed Ali, an Egyptian-Sudanese writer and activist and circulated from 1912 to 1920. The first issue stated that the Universal Races Congress of 1911 had brought to light the need for a “Pan-Oriental, Pan-African journal at the seat of the British Empire which would lay the aims, desire, and intentions of the Black, Brown, and Yellow Races — within and without the Empire — at the throne of Caesar.” The journal’s subtitle thus simultaneously diagnosed a problem — the tacit whiteness of the mainstream Anglosphere — and invited its readers and contributors to form a global Anglophone counter-public.

The 1913 Christmas issue that first caught our attention is at once ostentatiously Christmassy and not Christmassy at all. While it had “Grand XMAS Double Issue” blazoned on its cover and the title of the front-page editorial was “Merry Christmas to You All,” Ali makes it clear that the focus of the Christmas issue will be the grim world events that marked the year 1913 for non-white people: “Casting our eye over the world, in almost every non-Christian and non-European country, we see sorrow and suffering brought about by the greed and arrogance of ‘Civilized Europe.’” This summation effectively recasts a Christmas issue as a Christmas reckoning. In this sense, it reads much like a geopolitical version of The Christmas Carol, with Europe standing in for Scrooge. While the editorial begins with a Christmas greeting, it ends with an all-caps rallying cry for “the scattered forces of the non-European peoples”: “JUSTICE AND EQUAL RIGHTS FOR ALL MEN.”

Rather than a singular bounded and knowable empire, the object of the editorial’s critique were the shadowy circuits of global capital and racism. By foregrounding the commercial logic of racialized exploitation on the one hand and the dwindling faith of Europeans, the African Times and Orient Review’s Christmas issue draws attention to the commercialization of Christmas as a token of Britain’s growing imbrication in globalization and its discontents. Ali thus notes that “Europe has ceased to be zealous about the conversion of the heathen to a religion in which it has ceased to believe, and now the sacred name of “Commerce” is invoked to cover the appropriation of lands.” While in earlier times, he argues, “The Popes sought to heap up riches for the Church,” in 1913, “Cabinets seek the ‘prosperity of the People’ (and their own), but behind them stand the financiers who exploit the ‘people,’ drawing their gains from the sweat of their own race, with the same callous indifference to aught save the increase of their pile, as they exploit Turks, Indians, Chinamen and N****ers, making Cabinets dance to their tune.” Rather than decrying Christian hegemony per se, the editorial laments the vanishing of Christian values and ties the spread of crass materialism and its attendant exploitations to the global instability readily discernible on the eve of World War I.

Ali’s challenge, in manipulating an imperial form, ultimately comes down to a question of how to construct readership: if the notices of big game season that appeared in his newspaper are clearly for white people (travelers or colonial officials in Africa), the editorials are not. The experience of reading the addresses to the reader of the 1913 Christmas number of the African Times and Orient Review in 2020 is uncanny not only because of its pan-Islamic and anti-colonial bent but for another, albeit slightly embarrassing, reason. Because the refrain of “Do They Know it’s Christmas” is impossible to forget for those who lived through the 1980s, the process of parsing the “we” and “they” of the Christmas journal is uncannily familiar. The refrain of the song that is supposed to induce Western listeners to care about Africa only establishes its alterity. As other critics of the Band Aid song have noted, by virtue of having one of the oldest Christian churches in the world, Ethiopia hardly needed to be reminded of Christmas, while the discrepancies between the Julian and Gregorian calendar mean that Ethiopians celebrate Christmas on a different date from Western Christians. The point of Geldolf’s song is that “we” know it’s Christmas thanks to the various trappings first popularized by the Victorian Christmas issue: gifts, feasts, and celebration — but also, weirdly enough given its relative rarity in the UK, snow. The tragic absence of snow in Africa, we are to infer from the lyrics, is metonymic of the supposed lack of water and resources in all of Africa.

In the African Times and Orient Review, by contrast, there is also a “they” who do not know that it’s Christmas — only here the third-person plural refers to an inchoate white, inter-imperial business class whose power and allegiances exceed those of the British imperial realm. There is also a “we” in the opening editorial that reinforces the alterity of the “they.” Ali generally uses the editorial, royal “we” for his own voice in sentences such as “we send forth to all our readers the greeting appropriate to the great festival of Love and Peace to men of Goodwill.” Yet this “we” changes in the course of the same paragraph: “Welcome have been the visits to our offices of supporters from far regions… and hear their kind words of cheer and hope. In all cases we have parted friends at least, in most cases as allies and co-workers in the great cause.” In this last sentence, the “we” is no longer editorial but collective — a community in-the-making of anti-racist solidarity.

Seventy-odd years before Band Aid created their enduringly cringey Christmas song to draw global attention to a humanitarian crisis in Ethiopia of which Westerners would otherwise have been oblivious, the editor of the African Times and Orient Review chose to coopt a Christmas print genre to indict a global racial crisis closely connected to global capitalism. These two Christmas events of 1913 and 1984 are flashpoints in the history of Christmas forms. They are worth considering together because they function as each other’s negatives and reveal the seams between a British-imperial map of the world and the globalized one we have inherited.