When I was married and my then-husband and I visited Ireland, where half of his ancestors are from, everyone we met thought that I was the one who was looking for her roots. This thrilled me for reasons I’m not sure of. Was the actress in me proud of how well I could lose myself in another identity? Was it that I believed the Irish are the lost tribe of Israel — Leopold Bloom, Abie’s Irish Rose? Was it some latent Jewish self-hatred? Or was it simply the relief of knowing I could pass as Gentile?

My mother used to tell me that I looked like I’d stepped out of an Irish choir. Since I had strawberry-blond hair (she called it titian), a freckled fair face, and blue eyes, I could see that she had a point. Although the rest of my family also didn’t look particularly “Jewish” (by that I mean the stereotypical olive-skinned, dark-eyed, curly-haired, and hook-nosed look), they appeared different enough from me that my older brother, who never tired of inventing new ways to torture me, liked to tell me that I was adopted or, worse, fished out of the gutter by my parents, who’d felt sorry for me.

I grew up in the 1960s and ’70s in Tenafly, New Jersey, a suburb of New York City. The town had four elementary school districts. Mine, Smith, consisted mainly of nouveau riche, primarilyJewish families who lived in ugly split-levels and ranch houses on the town’s eastern hill. My best friend at Smith, Suzanne, lived at the bottom of the hill, near the train tracks. Suzanne was Catholic and had nine siblings. I often went along with her to the Sunday spaghetti dinners at her church. I always felt a little guilty about being there — for both betraying my faith and trespassing on hers, but my mother would tell me it was fine.

Tenafly’s four elementary schools fed into one junior high school and when I got there three of the new friends I made were, like Suzanne, good Christian churchgoing girls. They all lived on the town’s north hill, in stately brick Tudor houses, the oldest in the town. Like me, they loved acting, and dancing to show tunes. Amy had the same number of siblings that Suzanne did, nine — surprising, given that she was Protestant. Her family took wildly expensive vacations.

Her father and my father were both doctors, but unlike the Bloomingdale’s antique knockoffs in my house, her family’s furniture was shabby and threadbare, and they drove a beat-up Volvo. And they belonged to a country club. A club that did not accept Jews as members. Jews could come as guests, though, and Amy would bring me along with her to swim. It made me a little queasy with conflict, but the country club was a lot nicer than the public pool. I suspect that, unlike the spaghetti dinners, my swimming in that pool did bother my mother. But, like so many Jewish mothers, indeed like so many mothers of all kinds, what could she do but indulge her child and let me go.

Once, when I was 17 and my parents were away on vacation, I decided to throw a party. Word got out: open house at Susan Golomb’s place. The house got overrun with teenagers while a hippie boy asked me to “mellow out” on the roof of his car. As we were doing so, suddenly the house pitched into complete darkness. It turned out that kids from Tenafly’s blue-collar west side, literally the other side of the tracks, had pulled the fuses, stolen the stereo equipment, and finally, before the cops came, painted a swastika in large, thick black strokes on the front door.

A couple of months later, I went to a party thrown by a Jewish boy when a kid named John, who was as blond and blue-eyed as a Hitler Youth, started loudly making anti-Semitic remarks. My friend Lori, who was Jewish, yelled at him, “Do you know whose house you’re in?” She made John back down, and I was in awe of her bravery. Still traumatized by the desecration of my home, I had just stood paralyzed, ashamed by my own silence.

I had another friend, Janet Lipsky, whose parents were both Holocaust survivors. Her father had led two escapes from concentration camps; her mother, along with her twin sister, was one of “Mengele’s Children,” experimented on in horrific ways. The two survivors had met in America and attained the Dream, settling in Tenafly’s upper-middle-class East Hill and raising a brilliant son and daughter. But when Janet and I were in high school, her mother hanged herself. Four years later, on the anniversary of her death, Janet’s brother also killed himself. For all the running, her family couldn’t outrun the horror of its Jewish Ancestry.

After I left home, no doubt because of my “non-Jewish” looks, people often said anti-Semitic things straight to my face. How someone was being “Jewed down” in price. How “they” all stuck together; how “they” controlled the media, the banks, hell, the world. One time, after I’d become a literary agent, I went out west to California to stay with a writer who’d sent me an early, promising draft of a novel. She told me the Russian River was getting ruined by all the Jews moving in. I told her I was Jewish. There was an awkward silence. When the revised novel came in several months later, I didn’t think her revisions were good. If they had been good, would I have represented her book? Was it because of what she’d said that I thought the revisions were poor?

Before I married and now that I’m divorced, there was always the question of when to bring up my Jewish background. One New Year’s Eve I danced the night away with a man I’d just met. As we took a break to catch our breath, we got to know each other a little bit. We were both rock climbers and the children of doctors. At one point, I don’t know how we got on the subject, he started to patiently tell me that on Yom Kippur the Jewish people would go down to the river to put notes of atonement on small pieces of paper and watch them sail away. I wasn’t sure whether to acknowledge that this too we had in common. After all, had he been attracted to me because he thought I wasn’t Jewish? On initial dates with non-Jewish men when I feel the conversation drifting toward the subject of Israel or Judaism I preemptively mention that I’m Jewish. I do it to head off any anti-Semitic remark that might be coming my way. I realize that this amounts to a kind of prejudice itself, even if I can rationalize it as self-defense. And then if the man doesn’t call me, will the reason have been that I’m Jewish? (I always toss that explanation in with all the other “never knows,” like maybe I said too much, or too little, was too smart, or too dumb, my hair was the wrong color, and, of course, every woman’s old saw, I was too fat.)

Once, when I was starting to date the man who did become my husband, we were out walking with a good friend of his. Out of the blue, the friend asked me, “Are you Jewish?” I glanced at my new boyfriend and saw that the color had drained from his face. Was it the boorishness of his friend’s question? Or was he shocked that I could be Jewish? He was from Wisconsin — maybe he had never seen a Jew? I later learned, to my relief and delight, he had dated an Israeli before me. I made some lame joke about my curly hair covering up my horns, and the subject didn’t come up between my boyfriend and me again till we were making wedding plans.

My college boyfriend was Jewish and liked to say I was a Jewish man’s dream: Jewish, but I looked like a shiksa. Be forewarned: there are many among us who intentionally or not pass. Some of us, like Lauren Bacall, Scarlett Johansson, and Gwyneth Paltrow, are famous and beautiful. Each of us, I’m sure, has heard her share of anti-Semitic remarks. We toughen up. Some are pistols. My friend Lisa, in college, went out with a man named Flanders Lakewood. In a moment of drunken pique he yelled at her, “You slut, you whore, you Jew!” We couldn’t stop laughing at that one. But some of the insults were devastating. A black-humored man whom I lived with for many years texted me, during the ugliest stretch of our breakup, “When they come, I will be the first to point you out.”

Now I have a son. Like me, he has strawberry-blond hair and a splash of freckles across his face. When the Hasidim come around during the High Holy Days and ask, “Are you Jewish?” I always want him to say yes, to never deny his Judaism, whatever the pain it can bring. Though I had a fairly secular upbringing, my family was always culturally Jewish. I’m proud of my ancestors, who came here from the shtetls of Europe with no money, who didn’t Anglicize their names, who juggled their loyalty to their heritage with their desire to assimilate.

In 1946 my father’s family was showcased, in a special issue of the Saturday Evening Post called “Your Neighbors,” as the token Jewish family. My grandfather, the son of a tailor, immigrated from Latvia as a child. He went on to found the Everlast Sporting Goods Company, a Jewish immigrant who created an American icon. (Muhammad Ali’s Everlast gloves are enshrined in the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, DC.) But I wasn’t bat mitzvahed and have rarely set foot in a synagogue.

So, when my son, who is also being raised secular and has an atheist Irish Catholic father, asked to be bar mitzvahed last year I was surprised. Only a handful of his classmates are Jewish, but to him there’s something compelling about being a Jew. When I asked him the reason, he said it was the tradition. He won’t be of age for the ceremony for a while, and it would require that he learn Hebrew, something I doubt he’ll prefer to playing video games when the time comes. But when my rabbi cousin, by way of introducing him formally to Judaism, brought him to his temple and took the Torah scrolls out of the Ark and carried them to the lectern, and then put a prayer shawl over my son and a yarmulke on his head, tears welled in my eyes. I rooted frantically in my bag for my cell phone, so that I could take a picture and send it off to my father to capture the moment before it was gone. It might be all we’ll ever have if Jake decides that this was just a short role and not to be part of his identity when he becomes a man.

I wouldn’t blame him if that were his decision. In the months before Trump’s inauguration, hate crimes skyrocketed nationally; in New York City, where I now live, there was a 110 percent spike in such crimes, most of them targeting Jews. On January 9, The New York Times reported a spate of bomb threats to synagogues and Jewish community centers all over the East Coast, including the community center in Tenafly where my father still lives. Emboldened by Trump’s continuing dog whistles, Neo-Nazis marched on August 12th in Charlottesville shouting “Jews Will Not Replace Us” and the Third Reich slogan “Blood and Soil.” Trump’s claim that there were “many fine people on both sides” was a ball that White Nationals ran with. According to the Huffington Post, more than two dozen anti-Semitic incidents occurred in the two weeks that followed. What was once a private concern that I only had because I heard it said enough to my face has become publicly somewhat all too easy to believe — that the worst could happen here, too.

So I am grateful to the God I’m not sure I believe in that my son does not look Jewish. After all, I am a Jewish mother.

All names in this essay, except that of the author and her immediate family, have been changed for the privacy of individuals.

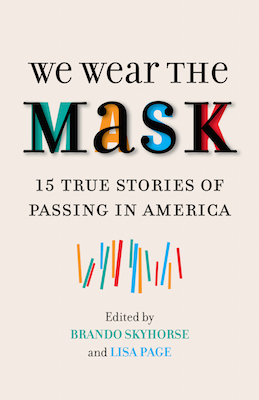

The essay “Jewess In Wool Clothing” by Susan Golomb is excerpted from We Wear the Mask: 15 True Stories of Passing in America, edited by Brando Skyhorse and Lisa Page (Beacon Press, 2017). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.