When Jojo and his family go to pick up his father Michael from Parchman Prison, they return home with an unlikely additional passenger. Richie — who can be seen only by Jojo and his toddler sister Kayla — is a ghost who has kept residence at Parchman for decades, haunting the site of his untimely death in an attempt to understand it. Richie was only a boy when he was incarcerated for spurious reasons, and he was only a boy when he was killed for trying to escape. Sing, Unburied, Sing, a finalist for the 2017 National Book Award, is a novel populated by living characters who contend daily with the consequences of state-sanctioned racial violence. Richie’s story intervenes in an otherwise 21st-century narrative to indicate that, when it comes to American racism, the past remains very much alive.

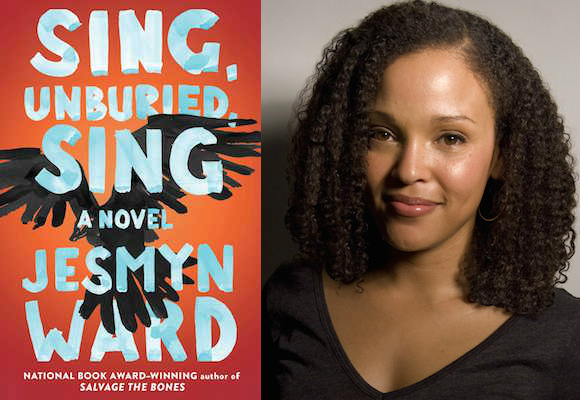

In 2011, Jesmyn Ward won acclaim for Salvage the Bones, her novel about a family living in the Mississippi Gulf town of Bois Sauvage in the days leading up to Hurricane Katrina. Since then, she has written a memoir, Men We Reaped, and edited an anthology about race in America called The Fire This Time. With Sing, Unburied, Sing, Ward returns to fiction and to Bois Sauvage to tell the story of a family haunted by ghosts.

While Sing, Unburied, Sing is a regional story in the sense that, according to Ward, it “could only happen in Mississippi,” the book makes a universal appeal to the urgency of retrospectivity in 2017. I spoke with Jesmyn Ward to learn more about the importance of listening to our ghosts.

¤

LOUISE MCCUNE: In the epigraph to your book, you quote Eudora Welty, saying: “The memory is a living thing — it too is in transit.” How might readers understand memory as a “living thing” in Sing, Unburied, Sing?

JESMYN WARD: In Sing, Unburied, Sing, memory comes alive and is embodied by the ghosts Given and Richie. They come alive and they interact with the characters. They interact with their loved ones, and they act on them.

One of the reasons that I love that quote so much — and why I think it is so applicable to the story that I’m telling — is because a question that the book is asking is about how the past bears on the present. For me, the quote about memory being a living thing is another way to say that the past is not the past, and that time isn’t linear. That’s a theme that I’m wrestling with in the book. These ghosts from the past haunt those in the present because of enslavement, because of Jim Crow, because of the terrible history of Parchman Prison and of places like Parchman Prison. All of that — which hypothetically happened in the past — reverberates into the future and into the present.

In a review of Sing, Unburied, Sing in the New York Times, Parul Sehgal pointed out the prevalence of ghosts in literary fiction in the past year or so. She references George Saunders’ Lincoln in the Bardo, White Tears by Hari Kunzru, Grace by Natashia Deón, and The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead. What do you make of the great number of ghosts in fiction this year? Are there any literary ghosts who inspired or instructed you as you wrote your own ghosts into being?

There actually weren’t any literary ghosts that inspired my ghosts. I think that my ghosts came from my non-fiction reading because I was reading a lot about Parchman Prison and Mississippi history in general. I knew nothing about those things, really. I read that there were kids — 12- and 13-year-old black boys – who were charged with petty crimes like loitering and then sent to Parchman Prison to be enslaved, tortured, and die. When I read that children were sent to prison because they were boys and because they were black, I knew that I had to have a character like that and that that character had to be a ghost. I wanted that character to be able to interact with characters in the present — Jojo and his family, who I was writing about.

I think that maybe one of the reasons that ghosts are figuring so prominently in literary fiction as of late is that writers are resisting. We’re pushing back against this trend that seems to be happening right now, where people in politics are attempting to rewrite history and attempting to undermine our understanding of what came before. That’s really horrible. A lot of writers are wrestling with a trend in the larger culture to deny what has happened in the past. Maybe that could explain the appearance of so many ghosts (who are reckoning with the past and bearing witness to the past) in fictional work lately.

I was struck by something you wrote in the introduction to The Fire This Time about how you had initially envisioned that you would categorize the poems and essays into three tidy sections: past, present, and future. You noticed though, when pieces started coming in, they skewed heavily toward the past and the present. Only three explicitly referenced the future. Did that surprise you? How did it feel to make that observation, especially as a writer who is trying to write against the tendency of people in power to rewrite history?

It did surprise me. It gave me hope to see that so many people were doing that kind of work, to see that so many people were really fighting back against the erasure of facts and knowledge. So on one hand it was heartening, but on the other hand it was disheartening because I think that it’s a skill that we need for survival. It’s something that engenders hope — we have to be able to imagine our future. It did make me a little sad to see that not many of us were imagining our futures.

Were there other resonances between The Fire This Time and Sing, Unburied, Sing? Were you working on those two projects simultaneously?

I was working on them simultaneously. I referenced Trayvon Martin in my introduction [to The Fire This Time]. At the time when I was working on Sing, Unburied, Sing and The Fire This Time, I was thinking a lot about Trayvon. I was thinking a lot about the seemingly endless list of young black men who were dying one after another.

I write about characters who are women in the book, and in some respects Sing, Unburied, Sing is asking questions about motherhood, about black motherhood, about womanhood, and about family. But at the same time, I think that the other half of the book is really concerned with black boyhood and black manhood. It’s about how, across generations, through the decades, and through the centuries, that personhood has been threatened. I was thinking about many of the same things when I was working on both projects.

You’ve said in other interviews that Jojo’s character was the seed that stirred you to write this book. This book, also, has been called a road novel and bears comparisons to The Odyssey. Did you always know that bringing Jojo to the page would mean sending him (and his family) on a journey away from home? Did you always know that it would be a journey to Parchman?

I did, actually. From the very beginning, I knew that Jojo and his mom would get in the car, and I knew that they were traveling to Parchman Prison. When I began working on the first draft, that’s all I saw the novel as. I thought, well, this will be a road trip, this entire novel. I thought it would be a road trip through the modern south, that it would be a little surreal and a bit bizarre. When I was starting out, those were the ideas that I had. As I did more research on Parchman Farm and discovered that kids like Richie existed, my ideas around the story evolved and changed. The story became something else. It became a ghost story, too. That discussion about time and about how the past bears on the present — it became more complicated for me.

Did Richie come to you with the same clarity that Jojo did?

Not as immediately, no. He didn’t. I had written three or four chapters at the point where I discovered Richie’s character. I thought, well, maybe later on in the book I’ll have a chapter from his perspective. He can speak, he can tell his story. I didn’t do that in the first draft. I completed a first draft, and he wasn’t there. I mean, he was there in scene, he was there in action, but everything was filtered through Jojo’s or Leonie’s point of view. I went through multiple revisions of the book, and when I say multiple revisions I mean like 12. I got feedback from friends of mine who are writers and went through more revisions. Then I sent it to my editor and my editor asked if I had thought about writing any of the sections from Richie’s perspective. It was only then that I went back and tried to hear him. I think I was afraid to write from his perspective because his perspective required me to build that entire world. I had to build an afterlife. That afterlife had to have some logic, it had to make sense. It had to feel real, and vivid, and believable for the reader. I was afraid to do that because I had never done anything like that before.

Parchman Prison, in Jojo’s grandfather’s memory, is guarded by inmates. He says it’s a place that’ll fool you into thinking it isn’t a prison at all because it doesn’t have any walls. When Jojo’s dad is there many years later, it’s low, concrete buildings and barbed-wire fences; he calls it a fortress. In your reading about Parchman, what else has changed from its earlier days until now? What has stayed the same?

It’s not a working plantation anymore. Inmates are no longer guarding other inmates. Back when [Jojo’s grandfather] and Richie would have been there, if one of the inmate guards killed another inmate who was trying to escape they would have been granted their freedom. That system no longer exists. They’re no longer whipped. They’re no longer tortured. But one thing that hasn’t changed between now and then is that the large majority of inmates are still black men. They still work while they’re in prison, and when they get out they’re still disenfranchised. They’re not able to vote. Their crime and the time that they spent there follows them. They don’t have full rights of citizenship. That part hasn’t changed.

Did you visit the prison as you were writing the book?

I actually did not visit the prison. I wish that I had the opportunity to, but I didn’t. My editor actually visited and took tons of photographs for me. She bought me a book and a collection of CDs that have all of the Parchman Farm songs on them that were recorded in the ‘40s and the ‘50s. I’m a new mom — I have a daughter who just turned five, and an 11-month-old. Between those two I couldn’t fit a trip to Parchman in.

You’ve talked before about this thing you call “narrative ruthlessness” — how, when you were writing Salvage the Bones, you resisted against an urge to “spare” the characters you loved so much from the realities of the place you were writing about. Was that something you were thinking about as you wrote Sing, Unburied, Sing?

It was definitely something I thought about when I was writing this book. I was thinking about it with every single character. Say, for instance, with Ma’am, Jojo’s grandmother. She’s sick with cancer at the beginning of the book. As soon as I knew she was sick with cancer, I was like, okay. There’s a strong possibility that that would lead to death. I knew that even though I would come to love her in the book, that if she had to die then she’d have to die. I couldn’t stand in the way of things that were happening to her.

I definitely felt that way with Leonie, Jojo, and [his sister]. The part of me that loves my characters and wants to protect them just wanted to lift the children out of that situation and take them away from their emotionally abusive, neglectful mother. But I knew that I couldn’t do that. They’re family, and I knew that they had to struggle through what they were enduring together.

I really felt that way with Richie. Richie is such a heartbreaking character, and that’s even more complicated by the fact that I know that kids like him existed. Part of me wanted to save him. I wanted to deliver him, while I was writing, from the life and the death that he had. I also wanted to ease his way in the afterlife. But then there’s something dishonest about that, you know what I’m saying? There’s something dishonest about being kind to my characters because the world, so often, isn’t kind to them. I thought about that with all my characters. It was constantly on my mind. I had to be honest. I had to be ruthless.

Is there anything that has surprised you about the way that audiences have received and responded to Sing, Unburied, Sing so far?

I’m delighted that people have responded so positively to it, especially because it’s a story that could only happen in Mississippi. Readers know that this is a story that could only happen in Mississippi, but at the same time they’re empathizing with the characters. They’re identifying a universality in the story. That’s been a nice surprise.