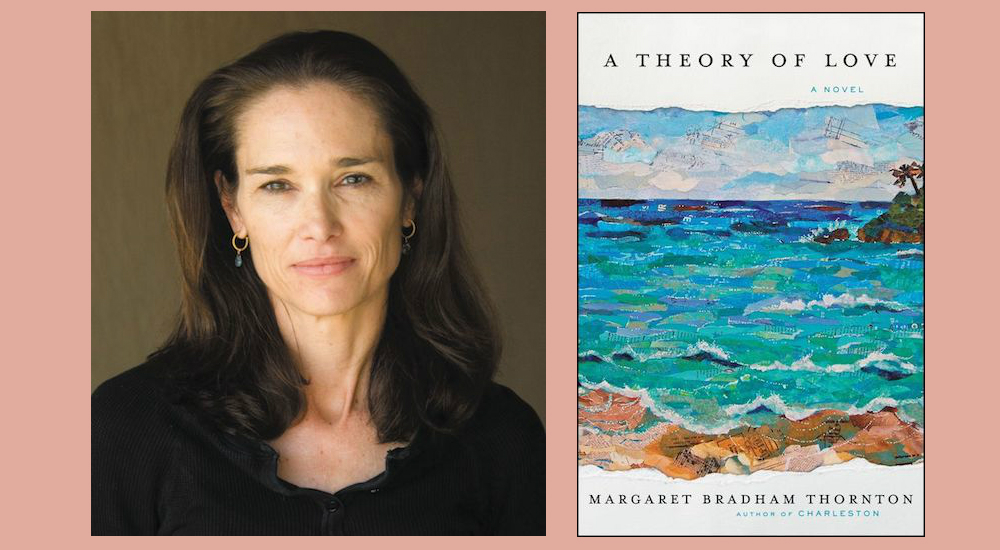

Margaret Bradham Thornton prefaces her second novel, A Theory of Love, with a Miltonian slice: “The World was all before them, where to choose.”

Thornton herself appears to have the world at her feet; she seems continuously, and contagiously, beckoned. Her first novel, Charleston, was acclaimed for its intimate rendering of the city itself. Her work on Tennessee Williams’s Notebooks, for which she received many honors, reflected a 10-year odyssey to trace and annotate the playwright’s instincts and obsessions. Thornton is a Princeton graduate who majored in English and trained in drawing before she went on to work on Wall Street. She was a state tennis champion. She is a serious gardener. Careful to draw the line between her fictional characters and herself, she nevertheless presents herself as a polymath; no one but a polymath could write her stories.

A Theory of Love takes its two primary characters from Bermeja to London and then to Saint-Tropez before carrying them ahead (and back) to Fontainbleau, Cala Blava, Tangier, Djemaa El Mokra, Milan, New York City, Chamonix, and Havana. The fantastical wealth, the late-night parties, and the drift through possessions all hearken back to Fitzgerald tales. The travel is a consequence of the high-profile financier work of Christopher, who proposes to Helen, a features writer for a London newspaper, in a moment that surprises both. Helen may not know Christopher as well as she’d like to — his profession, among other things, divides them, and his world, his many worlds, are not her own. But she feels safe with him, as the story begins, and soon the very velocity of their lives leaves little time for mutual discovery. Introspection replaces conversation.

Is there any theory of love that might save, or, at least, explain them? These are the questions at the heart of this novel. I wanted to know more. I wrote to Thornton and asked.

¤

BETH KEPHART: In Charleston, you were lauded for your commitment to the exquisite details of the city itself. Your new book is a many-places book, but each place has been immaculately perceived. Is it your training as an artist that is responsible for your desire to look so intently at cliffs and color, hills and osprey? Is it your work with stems and seeds? Or did dealing with money on Wall Street refine your appreciation for details? Or it all something else altogether — and something undefinable?

MARGARET BRADHAM THORNTON: I view the role of writer as part documentarian, so for me learning to look was part of the process of becoming a writer. I think I’ve always been particularly attuned to the natural world as it makes me feel more alive. Growing up in Charleston, I spent most of my time outdoors, and I learned early to navigate the wild natural world that surrounded me. Charleston is a narrow peninsula bounded by two rivers, and within 20 miles there are beaches and barrier islands and vast tracts of untouched land with beautiful cypress and tupelo swamps. When I was 14 or 15, I would take a boat across the harbor to one of the barrier islands and be gone all day. You had to learn to read the sky and the water, to feel a storm coming before you could see it. When I was a little older, I would ride my horse through thousands of acres of forest, and I had to be alert to the natural world to stay safe.

In the opening pages, as Helen and Christopher are first getting acquainted, they compare lists of favorite words. Helen is interested in words that “don’t have counterparts in other languages — such as schadenfreude or enamoramiento or shi.” Christopher’s favorite word, it is revealed, is sprezzatura, which he says means “to make whatever one does look as if it is without effort or thought.”

These linguistic preferences, to some extent, frame the rest of the novel. If we paid closer attention to each other’s favorite words, would we, as a species, be more careful about who we fall in love with?

Very possibly, though I came at this from the other direction. Helen’s fascination with these words — words that by their very existence suggest that an idea or emotion may reside more in one culture than another — tells us much about her. She is drawn to illusive things and concepts that have both intensity and peace and patience about them. They also are words that could be used to describe aspects of Christopher, so I think they are clues as to why she falls in love with him.

Helen’s choice of words reveals to Christopher her interest in other cultures and a certain fearlessness about crossing borders, exploring new terrain, both literally and metaphorically, and this aspect of her certainly appeals to him. Christopher’s ability to embody his favorite word, sprezzatura — to make whatever he does look as if it is without effort or thought — certainly appeals to Helen and keeps her off balance at the beginning of their relationship.

I found these words in very disparate places. For example, I found Helen’s favorite word, neverness, in The Paris Review interview with Jorge Luis Borges who said it was “a beautiful word, a poem in itself, full of hopelessness, sadness and despair.” He could not understand why the “poets left it lying about.” Helen is moved by foundlings and orphans, so rescuing an “orphan” word seemed right for her and was the spark for her conversation with Christopher. My understanding of shi, which refers to the moment when everything is in harmony, was aided by François Julien’s The Propensity of Things. And I discovered enamoramiento when I was walking past a bookshop in Eindhoven. I spotted a beautiful dustjacket in the window — it was a crop of Elliott Erwin’s 1955 photo of Pacific Palisades and the novel was Enamoramiento by Javier Marías, published in English as The Infatuations. Enamoramiento means more the act of falling in love passionately, obsessively albeit briefly, so it has much more a sense of intensity and obsessiveness than infatuation. In Marías’s novel, after the end of this enamoramiento, one of the character speaks of her former lover, “knowing that he is still on our horizon, from which he has not entirely vanished.” This image fitted nicely with my “entanglement” theory of love.

Christopher introduces himself, in the early pages, as someone who can speak, at near-monologue length, about himself. Then he quickly pulls back and becomes, in so many ways, a cipher. There’s conversation as self-promoting performance, you seem to suggest, and conversation as self-revealing truth, which takes, at least for some, too much energy. What conversations do you love best? Which conversations were easiest to render in this novel?

I enjoyed writing the early scenes with Christopher and Helen where he is flirting with her in a somewhat removed and amused way. I like the way he stands back and observes all that is going on. Their repartee culminates when Christopher answers her question, “What is the one thing you will do for me, only once, only for me?” Christopher’s answer, which I had not anticipated, felt as if it were a simple solution to a complicated algebraic equation. His answer moves them past this form of light repartee and they rarely return to it.

The conversations on the last night are the ones I loved writing because they are without artifice. Christopher has to confront what it means to love someone, and, at that moment, he is completely vulnerable. By the end of the novel, it felt as if his conversation with Helen was urgent and necessary. In the early stages of writing a story, I often begin with an idea of a character and at some point, if the character develops a heartbeat, then I know I may be on to something. And if I can get into the zone where they begin to take over and I am just following them — that’s when writing for me is at its most enjoyable. I should add that this period occurs in a much later draft than the first — the writing of which always feels impossibly difficult — as if I am trying to push a boulder up a cliff.

A Theory of Love is a novel, first and foremost. But it is also a container of ideas. Equipping Helen with the job of a features writer enabled you to explore a wide range of topics with the sort of depth one often does not find in contemporary novels. How did you choose Helen’s feature story topics? What did you love discovering as you did the research for her?

I had topics I wanted to write about so making Helen a features writer for a newspaper allowed me the opportunity to weave these stories into the larger narrative. I chose ones that had metaphorical possibilities for this novel, for example, the orphaned circus performer John Glenroy. Six years ago, I traveled to Cuba and I was amazed by the scale and grandeur of the buildings in Old Havana which surpass any of colonial America. When I returned home, I contacted a wonderful antiquarian bookseller in New Haven to see what they had on Cuba. There was not much, but I did come across this slim volume about an orphaned circus performer who had traveled to Cuba in the 1830s and ‘50s and of course I got sidetracked. I expected a colorful memoir but instead was surprised to find a voice that was uninflected and flat. Glenroy’s memoir was mostly a chronological list of all the places he had traveled with circuses along with the names of all the performers. In my novel I have Helen and Christopher try to come to terms with the tone and form of this memoir. Helen wonders if memory of dates and places stand in for affection, as surrogates for family, whereas Christopher wonders if lists give Glenroy immunity from loneliness. Their musings suggest aspects of their lives that existed before they meet each other.

Sometimes research for one novel can turn up ideas for another, as happened in this case. In my research on the foundling hospitals, I toured the Ospedale degli Innocenti in Florence which, besides having well-maintained and accessible records of the orphans, has an impressive collection of art on display given by one of its original benefactors who believed the orphans should grow up in the presence of beauty. Recently I have been thinking about that assumption, specifically what is the importance of beauty in our lives and what effect does its absence have on the human condition.

Does anything not intrigue you?

The subject that intrigues me the least is business and finance — which may seem an odd answer given that I went to Harvard Business School and worked on Wall Street. But I do have a bit of an explanation — part feminism, part curiosity. As a teenager, I played on the national tennis circuit and I practiced with boys, so I think that there was a part of me that wanted to see if I could get a job that was regarded as one of the hardest jobs with offers going primarily to male students. I also was curious about the world of Wall Street which, for me, was like the wild west.

This novel could not have been written without a deep understanding of investment practices — and shady deals. Were you putting your Wall Street experiences to use in the novel, or was research required here as well?

I certainly drew on my experience working on Wall Street, specifically how people speak about transactions which is more nuanced than generally portrayed in movies and television. So I wanted to document accurately the world I had known. I also wanted to bring to the surface the issue of breaking the spirit of the law while obeying the letter of it because there was always that tension in certain areas of investment banking especially on the trading side. I researched several cases involving securities fraud that were litigated in the criminal courts. I also read a few books on money laundering to understand the specifics of transactions such as the “smurf” which, in its simplest form, a drug cartel is able to deposit hundreds of thousands of dollars a day by getting a large group of “smurfs” to deposit cash in bundles of less than 10,000 dollars. Other areas of research included reading manuals prepared by UK law firms on how companies should conduct themselves in the event of a dawn raid by the Securities Fraud Office.

Helen struggles, throughout the novel, to understand what binds and separates two human beings. She takes on projects that she hopes will deepen her understanding about why people do the things they do. She applies lyrical thinking, as you write, to scientific fact, saying, at one point, “I have a theory […] I think that emotions experienced in a place stay where they are, and when you come back you encounter them, you find them again.” Helen will adjust or add to her theories as her life goes on, but she’ll remain desperate, it seems, for some kind of operative idea about the human heart. What is your theory of love?

I wrote this novel to try to answer or at least understand the question: what is it about the human condition that makes us want to be with another person? For me writing is more about exploring than explaining. I’ve always been struck how solitary most animals are in the natural world. Many spend most of their lives alone, and most die alone. And I starting wondering about why humans are so different. Why, for example, is marriage so prevalent across cultures? Compare the English-speaking world with China. There is nothing shared between the English and Chinese language, and yet both cultures embrace marriage. So what does that suggest about the human condition? Does it imply that the desire for some type of union or attachment is, while not a universal condition, one that extends across most cultures? A number of years ago, a friend sent me an article that explained in layman’s terms the concept of entanglement theory, the idea that two or more particles can interact in such a way that they — no matter how far they are separated in space — remain entangled. A measurement on one system predicts the outcome of a similar measurement on the second system. This idea struck me an apt metaphor for a theory of love. So I decided to write about a married couple without children because I think children can “skew” the “results” as they can be connective tissue or unwelcomed friction. Even though I set out to answer this question, I didn’t expect to arrive at an answer, only a more nuanced understanding.

What impels you to write fiction?

For me, it’s a way of examining questions that intrigue me. For my novel Charleston, I wanted to try to understand the idea that home never lets you go. For A Theory of Love, the question is: what does it mean to love someone? I thought a lot about that question in my 10 years working on Tennessee Williams. It is hard to find a love story in his work. In most of his major plays and many of his minor ones, women long for men who don’t want them. In The Glass Menagerie, Laura waits for gentleman callers who never come; in A Streetcar Named Desire, Blanche stays behind on the run down plantation Belle-Reve, waiting for five years for her situation to improve; and in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Maggie waits for Brick to make love to her. “You know, if I thought you would never, never, never make love to me again — I would go downstairs to the kitchen and pick out the longest and sharpest knife I could find and stick it straight into my heart.” And so the 10 years spent reading about one-sided longing must have had something to do with why I am intrigued by this question, “What does it mean to love someone?”

What impels you to write non-fiction?

Curiosity. When the project on Tennessee Williams came along, I was not a Tennessee Williams scholar, but the idea that I could edit and annotate his diaries and, with the backing of the Tennessee Williams estate, gain access to institutional archives and private collections was too intriguing to pass up. I should add that Williams’s journals were so disorganized and disparate that very few people wanted to take on this project because it was hard to tell if it would amount to anything.

In those 10 years, I read everything I could find, including over 2,000 unpublished manuscripts and fragments of manuscripts that Williams had written. Because he threw nothing away and typewriters do not have delete keys, I learned a tremendous amount about him and his creative process. In fact, I could describe my 10 years as a kind of apprenticeship of his creative process.

After I finished this 10-year project, I was offered a similar one relating to an abstract expressionist painter. I declined because, while those kind of projects take you very deep into one person’s life and their world, they are, by definition, confining, and they do not allow as much lateral movement as in the writing of fiction. (But I still think about that project — if I had 20 hours a day to work I would have happily taken it on.) So in the end, maybe your question gets to the heart of freedom and direction in which a writer likes to learn: vertically and narrowly or laterally and broadly.

From what practice have you gained the most enduring ideas of human nature?

The more I thought about this question the more complicated and nuanced it became to answer. The easy answer is to say, “from writing fiction.” Writing fiction is not unlike reading fiction. In each activity you inhabit someone else’s skin. I can find support from a number of great writers who have spoken about the power of fiction in amplifying experience and empathy. Kafka described the novel as being “the axe for the frozen sea within us.” George Eliot wrote, “Art is the nearest thing to life; it is a mode of amplifying experience and extending our contact with our fellow-men beyond the bounds of our personal lot.” And Eudora Welty said, “One place comprehended helps us understand all places better.” To look at a great novel such as Crime and Punishment, Dostoyevsky takes the reader into Rashkolnikov’s mind and makes us understand how someone can get to the point of murder. Truman Capote in In Cold Blood is unable to bring that kind of understanding, despite getting close to the two killers, Hickock and Smith, because he is always, by definition, on the outside.

The reason that I find my answer insufficient is because I think nonfiction is inextricably linked to fiction in that it is just beneath the surface of most fiction. So to speak of fiction without its debt to nonfiction seems impossible. Fiction has freedom that nonfiction does not in that it allows the writer to put characters in situations that probe their understandings and emotions. But even with these experiments, I find nonfiction essential in expanding the range of possibility. When you start out in nonfiction you do not know what you are going to find. One of the pleasures of reading or writing nonfiction is the surprises. People often respond in ways you would not have imagined. You just have to listen to podcasts like BBC Witness, for example to a 21-year-old RAF pilot’s uninflected description of seeing 50 German fighter pilots heading toward his squadron of eight pilots flying solo. He said no one said a word because they knew they had all seen the 50 planes at the same time. I doubt a fiction writer could come up with a more authentic response than this one of pure silence. In the 10 years I spent editing and annotating Tennessee Williams’ journals I did not expect to learn so much about resilience and perseverance. Success not only did not come so easily to him, it remained for only a minority of his writing life. On occasion, he wrote pep talks to himself — words I would have not imagined coming from him at the times that they did.

When faced with a situation in fiction I know nothing about, I search nonfiction accounts of experiences which, while not the same, may have relevance. For example, when I was trying to figure out how my character Christopher might feel about unfair charges being brought against him, I remembered David Foster Wallace’s essay on a journeyman tennis player who talked about not having the luxury of being able to get upset when he is unfairly treated at a tournament. In each case, these two men were trying to survive in a world where their ability — physical or mental — was the only thing that could save them. Neither had the luxury to waste energy.

So as a fiction writer, I am shaping a story, but just underneath the surface are discoveries found in nonfiction. This is the collage aspect of fiction that I love. You can take things from one place and use them in another. Tennessee Williams did this all the time. My favorite example is how he borrowed and amended a line from his 1933 letter to Harriet Monroe of Poetry magazine. He sent her a sonnet and asked “Will you do a total stranger the kindness of reading his verse?” Many years later he amended this line from question to declarative statement and gave it to Blanche as her exit line.