The LARB Korea Blog is currently featuring selections from The Explorer’s History of Korean Fiction in Translation, Charles Montgomery’s book-in-progress that attempts to provide a concise history, and understanding, of Korean literature as represented in translation. You can find links to previous selections at the end of the post.

From the moment Japanese colonialism collapsed, a fight ensued between “right-wing” and “left-wing” Koreans, a fight often regional in nature. Places like the island of Jeju and the city of Gwangju, became sites of rebellion and massacre; perhaps the single largest and most contentious, rebellion happened in Gwangju, where a ragtag band of citizens actually beat government troops back from the city in a short “spring” quickly drowned in blood. As Korea continued to modernize, political strife continued to grow and appear in literature.

Writers, such as Hong Hee-dam who wrote The Flag from the perspective of a young girl who finds herself in the whirlwind of the Gwangju Rebellion, have addressed this strife with a direct eye. Hong begins in the middle in a city giddy with the freedom it has for a short time earned, then works her way to its inevitable, and historically accurate, conclusion. Hong starkly contrasts the responses of the intellectuals of the city with that of its workers, implicitly arguing that it is only the workers who can ever bring a real threat to a regime: intellectuals are versed in the language of oppression and revolt, but only workers truly experience it. Too subtle to make a full-fledged indictment of intellectualism, Hong tells a story that also quite clearly shows that the “cowardly” intellectuals were the only ones who foresaw the tragedy that lay in store for Gwangju.

Lim Chul-woo’s Straight Lines and Poison Gas — At the Hospital Wards indirectly focuses on the Gwangju Massacre. The indirection of his decision never to actually name the massacre happens because he wrote the story in the 1980s, a time in which a public attack on the government, or even discussion of political dissent or oppression, was extremely risky. He drops the reader directly into the life of an ex-cartoonist speaking to a doctor after being dropped off at the hospital by detectives who have been torturing him and likely plan to return to the task later. In flashbacks, the narrator reveals that he once lead an ordinary life, but fatefully drew a cartoon that aroused the ire of authorities.

The content of the cartoon is never revealed, but it causes the cartoonist to be taken in for questioning. The questioning comes complete with a touch that will remind readers of the real lives of writers Yi Mun-yol (about whom more later) and Choi In-hoon, with a semi-concealed threat by the police that they “remember” one of the narrator’s relatives, a political dissident who went into some kind of exile or died in hiding. This threat, and the recognition it brings to the narrator that he is powerless and entirely observable, opens the floodgates in his mind, and he is overtaken by semi-hallucinations, all barely concealed flashbacks to the Gwangju Massacre. The interrogation scenes have a hint of Kafka, and the descent of the narrator is reminiscent of familiar stories such as George Orwell’s 1984.

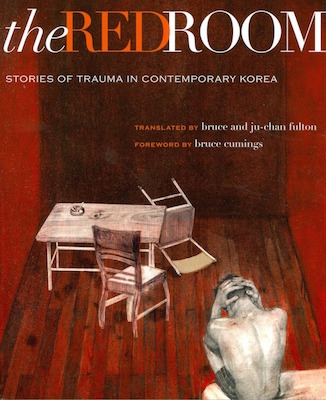

Lim has previously been translated in the three-novella collection Red Room, which takes its title from his contribution, another story focusing on the relationship between the interrogator and the interrogated. It features dual and dueling narrator-protagonists, the first a mild-mannered everyman/salaryman named O Ki-sop whose casual act of kindness many years before, and slightly suspect family background (the age-old Korean conflation of traitorous individual family members as evidence of traitorous families), combine to bring him to the attention of the Korean state security apparatus. The second, detective Ch’oe Tal-shik, can say, like Macbeth, “I am in blood, / Stepp’d so far, that should I wade no more, / returning were a tedious as go o’er.”

Telling the story of Detective Ch’oe‘s attempts to break O Ki-sop down, Lim denies any hope of escape from political trauma, its lessons burned in too deeply, and too recurrent, to avoid. At its conclusion, Detective Ch’oe enjoys and endures an epiphany of revenge featuring a disturbing and vivid sanguinary image: “A blood-colored sea filled the room … As I prayed, I felt with vivid clarity a sacred joy and benevolence envelop me with warmth, before beginning finally to fill the Red Room.” O Ki-sop, the mild everyman, becomes a vessel of hatred: as he finally wanders home in a daze, he accosts a stranger. “Something is rising inside me, something hot and burning,” he says. “It’s spreading hot throughout me, building an enormous heat — It’s my rage.” And so the cycle of trauma continues.

One more writer deserves a close look, and that is Yi Mun-yol, whose general suspicion of power, be it in the hands of dictators or the workers, placed himself outside the “normal” stream of post-dictatorship writers. Yi wrote across a wider range than some of his contemporaries, from a historical novel about what might be the world’s first beatnik poet in The Poet, to childhood allegories of fascism and freedom in Our Twisted Hero, to semi-hallucinatory odes to love in Twofold Song. Yi is also an interesting political case: his father’s defection to North Korea put Yi under suspicion of being a spy ever after. Consequently, even in a relatively traditional tale of a historical-mythical poet of the past, he could find a political meaning and turn a novelistic biography into political allegory. The Poet, an amusing story of the titular vagabond named Kim Sakkat, is also a deeply felt meditation on sins of the fathers, personal betrayal, and the isolation of separation from political society.

Our Twisted Hero is the book for which Yi Mun-yol is best known in English. The story of Han Pyongtae, a new student dealing with a classroom bully, it also presents a political allegory with hints of Orwell’s Animal Farm, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and even a bit of William Golding’s Lord of the Flies. Beneath its simple schoolroom setting, this very short novel meditates on authoritarianism, and how intellectuals who might oppose it can eventually be brought to heel by it, either through a process of intimidation or one of assimilation and ease. Written seven years after the Gwangju Massacre, it makes a skeptical comment on both the government of that era and the “democratic” one that eventually replaced it.

In Pilon’s Pig, Yi tells a similar kind of story about the uselessness of trying to overcome power, as one power can only be replaced by another power and self-determination remains impossible. He takes the position that power itself is dangerous — that, as the saying goes, absolute power corrupts absolutely. The narrator Lee is getting out of the Army and, entirely sick of it, has decided to take a commercial train home. Having wasted his money the previous night, however, he finds himself riding the troop train back home. When a group of elite troops boards the train and puts on a singing performance for “donations” (which are in fact extortions) a short drama ensues dealing with power, the cowardice of both power and powerlessness, and what happens when the powerful and the powerless change places.

When he first boards the train, Lee meets an old frenemy called Hong Dong-deok. Otherwise known as Hong “Dunghead” he displayed legendary incompetence back when he and Lee served together. Bizarrely, as the power relations on the train car ebb and flow, it is the drunken Hong who seems to fare best. He doesn’t really react to anything, investing no belief in any system of power, nor even seeming to give it much thought. Dunghead is a questionable kind of heroic survivor, unperturbed if not wise, and yet he survives without any trauma. Readers of philosophy will recognize, in Dunghead’s approach, the meaning of the story’s title.

Yi’s underlying argument relates to the elimination of the Korean dictatorial government and its replacement with a democratic one, a government “of the people.” He subversively suggests that one may not be that much better than the other, but that they simply address different issues. Further, he proposes that the shift from dictatorship to “democracy” may just replace one kind of abusive power with another. Religion also continued to be a topic of some importance and also, as usual, a vessel for power. In Lee Dong-ha’s A Toy City, starving families are driven to the church for food. There they are also introduced to a kind of Christianity,and in one scene the narrator’s mother asks how one prays in Christian manner:

“Reverend, will my boy’s father and sister be able to come home if I believe in Jesus?” This was her last wish.

I clearly heard Reverend Cha’s easy answer. “Yes. Just pray to Jesus. Then the day will come when the entire family can live together.”

Mother asked again, cautiously, “How does one pray, Reverend?”

Reverend Cha replied breezily, “Do it like you would to the Wise Old Goddess of Maternity.”

The specific ceremonies and beliefs of the religion are not as important as the bowing of heads before that religion. That all the religions were still in play is revealed by how casually they are dropped into these works. In Park Wan-suh’s Who Ate Up All the Shinga, for example, Park’s grandfather yells at her for clumsy ice-skating: “’Don’t you realize you’re humiliating the entire family?’ he yelled. ‘And a girl, at that? Don’t you have any better games to play than imitating a shaman’s blade dance?’” Park treats Buddhism in a similarly light-handed way in In the Realm of the Buddha, whose narrator casually describes her knowledge of Buddhism as enough to earn her “a score of 50 out of 100 on a test. It was like looking at something through glasses worn on the tip of ones’ nose.”

Solemn explorations of religion and their interface with power include Hwang Sok-yong’s 2001 The Guest, which also deeply explores the cost of Korea’s historical split. In his author’s note, Hwang calls the story “essentially a shamanistic exorcism designed to relieve the agony of those who survived and appease the spirits of those who were sacrificed on the altar of cultural imperialism half a century ago.” In fact, the structure of the book is based on the traditional Shamanic gut and explores the horrific cost of the Korean ideological split, and its story is based on an actual atrocity that pit Christians against Communists. It begins with two brothers in New York: Ryu Yosop, who is about to return to North Korea to visit long-lost relatives, Ryu Yohan, who was one of the pre-eminent killers in the incident.

Yohan dies just before Yosop leaves, and armed with only one of Yohan’s bones, Yosop departs for Korea to meet his family, perhaps make peace with his past and leave his part of his brother’s remains on North Korean ground. The story alternates between Yosop’s not-humorless account of the events of his trip and the events he begins to share with the ghosts of his past. The description of the massacres is excruciatingly detailed, but in the manner of history rather than of a horror show. The book includes a classic scene of farce (similar to the scene in An Appointment with my Brother in which the eponymous brothers tussle over North-South politics) in which Yosop is treated to a series of “survivor” stories from North Koreans that both he and the “survivors” know to be completely imaginary.

The book’s historical background is a series of atrocities in Northern Korea that, while originally blamed on U.S. troops, were actually internecine fighting between villagers separated by Christianity and Marxism (each a “guest” in terms of the title, also an allusion to the smallpox imported from the West) in which the once-friends butchered each other brutally. Hwang’s book caused a firestorm of criticism from both North and South Korea, both of which preferred to believe that such evil events were foisted upon Korea by foreigners. The story is perhaps best summed up by a quote from one of the characters: “Show me one soul that wasn’t to blame!”

Older political themes also continue to resurface in novels such as The Investigation by Jung-myung Lee, a crime thriller wrapped in a historical novel of politics with strong aspirations to literary fiction. Set in a prison camp in Fukuoka, Japan, near the end of World War II, the novel’s historical aspect focuses on the prison-camp life, and death, of real-life Korean poet Yun Dong-ju (author of Sky, Wind and Stars), who did in fact perish in such a place, though under uncertain circumstances. A young Japanese guard named Yuichi Watanabe is tasked by his boss with uncovering the murderer of a colleague, Sugiyama, killed in brutal fashion and hung with his lips sutured shut.

Watanabe is in parts innocent and clever, and when he unearths and gets a confession from the murderer, the crime drama has only just begun. As Watanabe traces the roots of the murder, he uncovers other crimes, an audacious escape attempt by Korean prisoners, the extent to which literature can affect even the most hardened heart, and some surprising revelations about many other characters, including an evolving understanding of the brute Sugiyama. In the course of this “whodunit,” Watanabe and the reader are treated to several entertaining reversals and unexpected twists. Lee also manages to fit in quite a great deal of history, introducing an entire slice relatively unknown in the west. This is a wonderful skill, as the history both goes down easily and advances the story.

The Miracle on the Han did amazing economic things for Korea, essentially propelling it from the third world into the first in about four decades. The breakneck speed of this change, however, often had a displacing and confusing effect on society which authors attempted to portray. It also occurred under the control of a military dictatorship, a type of system many authors were already both familiar with and contemptuous of. As the Miracle took place, Korea became an economic success on an unsteady path towards democracy, and as these changes became clear the appeal of “old” literature waned somewhat. Authors then had to look for new topics and writing styles to reflect the new Korean reality.

Previous posts in this Korea Blog series:

Where is Korean Translated Literature?

What Shaped Translated Korean Literature?

Why Does Korean Literature Use an Alphabet?

How Did Korea Get Fiction in the First Place?

Heroes, Fantasies, and Families: What Went Into the First Korean Novels?

Enlightenment Fiction and the Birth of the “Modern” Korean Novel

Literature Under the Japanese Occupation

Literature as Japanese Colonialism Fell

Deeper Into the War’s Aftermath, a Deeper Sense of Separation

The Social Tragedies of the “Economic Miracle”

Alienation, Politics, and Women

Charles Montgomery is an ex-resident of Seoul where he lived for seven years teaching in the English, Literature, and Translation Department at Dongguk University. You can read more from Charles Montgomery on translated Korean literature here, on Twitter @ktlit, or on Facebook.