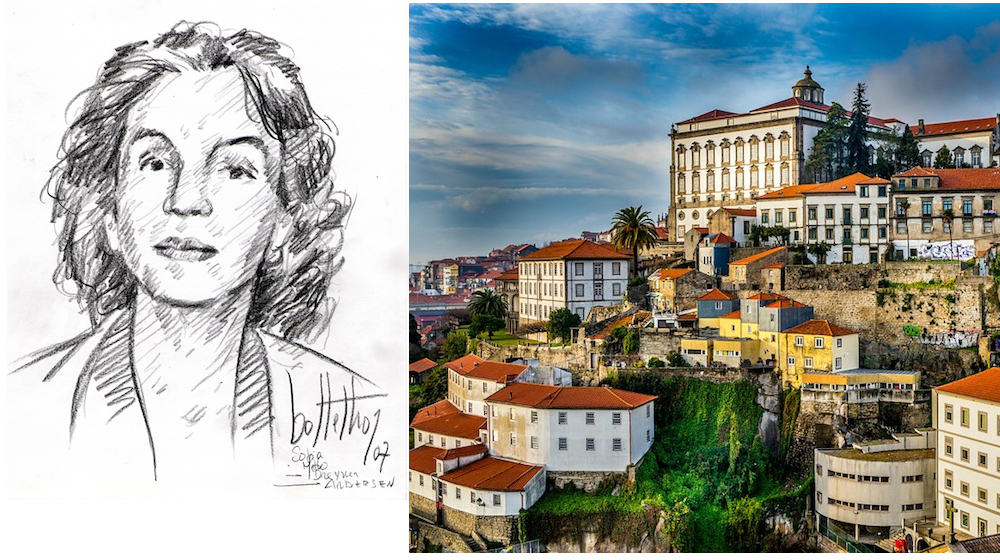

Recently, my job took me to Porto, Portugal. Never one to look a travel gift horse in the mouth, I decided to make the most of my trip and visit with a literary ghost. There are fewer of those in Porto than in Lisbon, but it doesn’t mean that the northern city is devoid of literary life. Pessoa and Saramago are the Portuguese writers I know best, but neither of them were from Porto, nor did they ever live there. Instead, I dove deep into Porto’s literary life and found Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen, a poet who won major prizes, like the Portuguese Writers’ Society prize for poetry in 1964, served in Parliament, and is beloved in Portugal. She’s a native of Porto, and in her collection of short stories, Exemplary Tales, she sets some of her stories in and around the coastal city.

There isn’t much available in translation to English by Sophia, as she’s commonly known in Portugal, and my Portuguese is too poor to understand and appreciate her in her native language. I placed a special order for the 2015 translation of Exemplary Tales by Alexis Levitin and tucked it in my bag for a weekend in Porto. Taking her with me offered a window into a history that I knew very little about prior, but was eager to learn. Sophia doesn’t shy away from illustrating moments in Portuguese politics and social life, often giving her stories a very distinct sense of time within the scope of Portuguese history.

As soon as I read “Beach” and “Homer,” I knew I had to go to Foz do Duoro, the beachside neighborhood near which she was raised. The beach of both of these stories is not named, but sitting on a seaside terrace sipping port, it’s easy to imagine her here, too, in her youth, watching the ocean break against the rocky shore.

In “Beach,” she describes an evening at a seaside club in the 1940s, and while I couldn’t find one of those (nor did I think I’d be admitted if I had), I did find a place to sit and feel the presence of the ocean as she describes it. Appropriate to my own experience of asking her ghost to tell me tales of a time long gone, she writes of a man “who had come to sit with us” and how he “spoke on, mixing his words with time, the night, the tumult of the sea, the breath of the breeze among the leaves.” Speaking of poetry to the young people in the story, this man explains obliquely his understanding of time and the immortal elements of the world. It foreshadowed my own experience sitting with Sophia.

I wandered the road alongside the beach in Foz, stopping to traipse onto the sand where I could. There is a restaurant and bar tucked in between the road and the ocean, hidden by lush foliage. Praia da Luz was my spot to sit and enjoy the beach about which Sophia wrote. I ordered a ruby port, after trying to use my limited Portuguese and only confusing my waitress. Port seemed to be the only appropriate drink while in the town that shares its name with its prized export.

“Homer” tells the story of Buzio, a man who roams the beaches and the beachside neighborhood, begging for bread. Walking to the bar where I sat down to read, it was easy to imagine him striding down the beach toward me, clambering over the rocky outcroppings that make the sea break dramatically around Foz. She writes of the beach in that story, “And all along the length of the beach, from north to south, till lost to sight, the low tide was exposing dark rocks covered with shellfish and green seaweed framing the water. And behind them, three rows of white waves were breaking incessantly, gathering up and unfolding, constantly crashing down and constantly rising again.” The beach does not seem to have changed since her day — the waves crashed again and again over the rocks that dotted the shore. There is a thrill in realizing an author I’ve enjoyed has stood in and seen the same place I am. Knowing that Sophia was inspired by all that I saw, while sitting on a patio drinking port as the sun set over the Atlantic, made my evening magical.

One of the great things about this collection is the introductory notes by Cláudia Pazos-Alonso that gave me context on a well-known Portuguese figure who is fairly obscure in the U.S. Sophia’s Catholic faith is evident in her stories, providing searing indictments of many of the culturally religious who do not heed the lessons of the God they profess. Her anti-Salazar stance comes through her work as well. If, like me, you aren’t familiar with Salazar, he was the dictator who ruled Portugal from 1932 to 1968. He heavily censored writers and employed secret police to question dissidents, both of which played a part in Sophia’s life as a popular writer and vocal dissident of his regime.

Salazar’s rule and its impact were new to me, but Sophia was an excellent guide through the lives of those who resisted through various means, including those religious who did not agree with Salazar’s demand for a toothless faith that eschewed the political in favor of the social. Sophia’s own life demonstrated that dichotomy, and in “The Bishop’s Dinner” and “Three Kings” she creates allegories of those who show true commitment to the tenets of their faith and those who chase after false idols. The bishop of Porto, who was exiled during Salazar’s rule, even wrote an introduction to “Three Kings,” connecting the real life consequences of resistance to the fictional.

Sophia writes in “The Bishop’s Dinner”: “And he saw that it was as if all the things that the man owned had formed a thick wall around him, separating him from reality.” In this story, she accuses those who value their good place in society over the true demands of their faith, and it felt as current and condemnatory now as it must have to her initial readers. That self-absorption and comfort found in one’s possessions and social status is not unique to Salazar’s Portugal, but is a universal condition.

I came to these stories expecting to discover a new-to-me writer — not to have my own practices questioned. Sophia’s allegories feel like an unexpected call to action that I didn’t expect when looking for a book that would help me envision life in Porto in another era. What a treat to read something that cuts through the metaphoric walls I’ve erected around my own self in order to insulate me from the world. I want to see through my possessions, through my roles in society, and allow myself to be transformed and convicted as some of the characters in “The Bishop’s Dinner.” When I sat down on the beach patio with a drink, I didn’t know I was going to be challenged. I hope that I am a self-aware enough reader to always come away from reading with something new and transformed within me.

Sophia gave me glimpses of the past, and I could see young people in the fashions of the 1940s lingering around a beach club while I explored the beach and its environs. In addition to that aspect of the past her works provided me, I loved that she gave me enthusiasm to be both genuine in my beliefs and more ardent in my stance against rulers who do not operate with their citizens best interests at heart.

In our present era of resistance for those who see and despise the policies of the current political administration, it is encouraging and illuminating to read fiction that tells the story of those resisting in times past. Salazar’s rule was not so long ago, and in reading Sophia, I found a new voice to champion long-term resistance through art. Sophia said “A poesia é necessariamente política” or “Poetry is necessarily political.” She did not see her art and her work of dissent as two separate parts of her life, but essentially intertwined. That encouragement that creating art is an act of resistance was a beautiful lesson to take in while enjoying all that Portugal now has to offer.

As I continue to write this series, I find myself thinking about what each writer leaves me. Sometimes it’s very practical writing advice, sometimes it’s a window into history, or sometimes it’s an appreciation of a new author. With Sophia, I read through her book, wondering what she would tell me. The call to resistance and authenticity are a big part of what I hear Sophia tell me as the two of us sit together while the sun slowly slips into the expanse of the Atlantic. I also carry with me a sense of wonder as I think about how she used her fiction to indict the people and practices she disliked with a deft hand that made its impact greater than a political screed.

I watched the sun set over the Atlantic in good company, with a writer whose poetry shines through even in her prose, and whose very life serves as a lesson in how to use art to resist.