The following article is the fourth in a five-part series about the movement at the Standing Rock Indian Reservation. The mobilization, of people and resources, which was spurred on by the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline, began an unprecedented convergence of hundreds of Indigenous Tribes, and thousands upon thousands of people. The series, which was originally written as a single piece, offers the reflections of Brendan Clarke, who traveled to Standing Rock from November 19th through December 9th to join in the protection of water, sacred sites, and Indigenous sovereignty. As part of this journey, which was supported by and taken on behalf of many members of his community, Brendan served in many different roles at the camps, ranging from direct action to cleaning dishes and constructing insulated floors. He, along with the small group he traveled with, also created a long-term response fund, which they are currently stewarding. These stories are part of his give-away, his lessons learned, and his gratitude, for his time on the ground.

CHIEF LEONARD CROW DOG AND THE WYRD

The word “weird,” as it is used today, means something “odd,” or “strange,” “something out of place.” But the word has a deeper origin in the old English word wyrd, which has more to do with fate, synchronicities, and becoming. It is a concept that speaks to the inexplicable “coincidences” that seem too connected to be written off as pure chance. Ironically, the more I have paid attention to the wyrd, the more logical (i.e. motivated by reasonable causes) the world seems to be. So too, have the connected movements of the world become more mysterious, and harder to grasp or fix into time or place. It is a paradox, and one that deserves to not be explained away.

What follows is a wyrd story. I do not fully understand it all, and I ask of you, in this written telling, to receive it gently.

Amidst all the preparations — the packing, the fundraising, the planning, and the listening — there was an enduring whisper within my being. It said, very simply, that I needed to do some form of spiritual, emotional prep work, what Marshall Rosenberg, the founder of Non-Violent Communication, might call “despair work.” Basically, I needed to get as clear as I could before going to the camp, so that I would not have to do that work there.

Not knowing what this prep work might entail, or how to go about doing so, I asked for support to explore this, and was offered the chance to sit with my partner Shay, and a circle of close friends. There is much to convey, and little that can be said in words, about how that process unfolded. What I will share here are two important insights. The first was that my trip to Standing Rock was rooted in a context of my Dutch ancestors in the region. This connection had been weaving itself into my preparations in various ways. What came clear during this time in circle was that I was not just going for myself, but also on behalf of my ancestors.

The second insight came through a physical experience, which began as a tremendous heaviness in my legs that came during part of the despair work. Shay noticed this and asked me to explore what was happening. What became clear was that my legs were tired, and heavy with the weight of an elder who can no longer carry the burden alone. My back felt achy, and I leaned forward, allowing for a gestalt to take place. We went deeper and deeper into the feeling, and relief came only when everyone present stood up and joined me in a common movement, in a circle. Afterward, still standing in a circle, the only words that I could find to describe my experience were: Wounded Knee, a place whose name and story I know of, but do not truly know. It was inexplicable.

Two nights later, I was standing around a fire, being sent off with three others on our journey to Standing Rock. There were two women, and two men: Melodie, Justine, Jiordi, and me. My friend Melodie spoke first, and the first thing she said was that her legs felt very heavy, achy, and tired. She and I had not spoken at all about the despair work.

A few days and more than one thousand miles later, Melodie, Jiordi, and I pulled into Sicangu-Rosebud Camp at the edge of the Cannonball River and the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation. We met with other friends who had arrived a few days prior and set up two tents where Curly and Donna, the camp hosts, had told them to do so. Between the two canvas wall tents was a flagpole bearing the Dutch flag. Of all the many places to be on that land, we had landed in Netherlands camp, and as far as I could tell, at this point, we were the Netherlands camp.

Within a few days, I started to set up the wall tent that we had brought with us to donate. Curly said that a good place to do so was between the two wall tents where we were staying, and the large elder’s tipi just north of us. I had barely finished setting up the shelter, with help from a few others, when a man named Hugo came over and asked if we had any places for a group of Lakota elders to come and stay. They were at the casino and needed a warm place, as well as some shoveled pathways, as one of them, an elder named Chief Leonard Crow Dog, was in a wheelchair. We brought Hugo inside the tent, and he said that it would work just fine.

The next day, I spent most of the day across the river, working on winterization projects. When I came back to our camp, I found the wall tent occupied, and with a raging fire in the woodstove. At the center of attention was a man behind a table, sitting in a wheelchair. He was Leonard Crow Dog. He is a Lakota medicine man and the former spiritual leader of the American Indian Movement (AIM). I later came to find out from Hugo that Leonard’s debut on the political scene occurred in 1973, at Wounded Knee, when tribal members took over the town in an act of protest of corruption and to reopen negotiations for the many broken treaties with the U.S. government. To give a sense of the position of this man, when the veterans at Standing Rock publicly apologized to the Lakota on behalf of the U.S. government, they apologized to Leonard Crow Dog. Here was an elder, without the use of his legs, who has been carrying the burden of Indigenous sovereignty since before I was born. And here, I, as the descendent of European immigrants to this land, was able to offer shelter and a warm space to land.

I do not pretend to understand the workings of the wyrd; they are mysterious, and hard to make claims upon. What I offer instead is this story, hinting at some greater movement in the cycle of things, which I cannot explain away. Random chance cannot explain why my preparations to go to Standing Rock led me not only into stories of my ancestry, but specifically my Dutch line, only to arrive in the lands where they long-ago arrived, and live for weeks under a Dutch Flag. It cannot explain, why I was left with the words, “Wounded Knee,” and the tired, immobile legs of an elder, long burdened with the weight of the world, only to later meet Leonard Crow Dog, as he sat in his wheelchair, in a tent I had just erected. I choose instead to bear witness to some deep current of healing, capable of magnetizing these pieces together. It was a humble privilege to support a Lakota elder to be warm and comfortable, while other descendants of settlers offered their apologies, and asked for forgiveness, in the land of the Lakota, where my ancestors gave birth to my great grandfather in 1878, just over a decade before the Wounded Knee massacre. It is one opportunity among many, to stand in a moment of healing that ripples in the world of the ancestors and the future generations alike. It is to remember the ways of the wyrd, and bend my head to their guidance.

THE VETERANS

Days passed, and the snowdrifts grew and shifted. Construction of the DAPL continued around the clock. The routine days of ordinary magic and extraordinary diversity carried on. The next great influx to camp was the veterans.

Beginning on December 3rd, veterans began pouring into camp. Extra structures were set up, the legal tent was flooded, and the road was backed up with bumper-to- bumper vehicles as far as the eye could see. For the first time that I witnessed, major news networks sent their reporters in vans bearing satellite dishes on their roofs.

The plan for the veterans to come had coincided with December 5th, the date that local law enforcement had named as the date that they intended to close Oceti Sakowin. What had begun as a group of 400-600 veterans soon became more than 2,500 who were now on their way. They were veterans of Vietnam, Korea, Iraq 1, Iraq 2, Afghanistan, and surely other wars and conflicts. Perhaps equally as staggering as the number of veterans, was looking at the spread of ages and realizing that as a country, there is not a single generation that has not been involved in some war, stretching back to before the American Revolution. In fact, the frequency of major wars has only increased since the end of World War II, “the war to end all wars.”

A significant number of the veterans who arrived were Native, which is especially noteworthy considering the relative remaining population sizes of the Native tribes as compared to those of European descendants. This may be accounted for based on many factors, including cultures that honor warriors, unemployment rates that leave nearly one out of every two adults out of the work force on the largest reservations, or any of many other possible reasons. Nevertheless, reflective of the U.S. military itself, the vast majority of veterans who arrived were white men. Given the historical relations between the U.S. military and Native Americans, the openness on behalf of the Indigenous leadership to welcome so many veterans was itself a humbling occurrence.

What ensued was a scene as beautiful and complex as any I have been a part of. There were gray-haired representatives from Veterans for Peace, clad in olive drab with white doves stitched into their fabric, walking on ice-packed roads from one place to the next. There were sweat lodges that were centered on prayers for veterans. There were arguments and cussing, and a few people who had been taught violence, who seemed always a bit too ready to meet with conflict again. There were fireworks and flareguns competing with beating drums and Native songs. It was a strange and perhaps unprecedented mixing of cultures.

Having arrived, like many others, with high hopes and a short timeline, many veterans began organizing for actions on the barricaded bridge. On December 5th, a group of veterans marched toward the bridge, some in military step. The wind in the hills picked up speed. As they reached the bridge, the light flurries began to cloud out visibility and thickened into a blizzard. The veterans were met with a barricaded bridge, but no law enforcement on the other side. Apparently, the law enforcement protecting the progress of a corporation’s pipedream was unwilling to stand its ground in the face of the veterans, or perhaps the blizzard. Seeing the opportunity to advance, many in the crowd urged the group to cross the bridge. Those who were organizing the march, held firm to their intention, which was simply to go to the bridge, not to cross it, and thereby risk inciting violence. As these two ways of being, and ways of thinking bumped up against one another, all within the crowd on one side of this bridge, the blizzard kept increasing in severity. In the end, it was the wind and the water from the ocean, frozen on its fall from the clouds, which forced the crowd to turn back, to prevent hypothermia and frostbite.

In the midst of all these changing circumstances, the camp received word that the day before, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the body legally tasked with permitting the underwater drilling, had denied the easement to do so. Energy Transfer Partners responded with a press release saying, they were “fully committed to ensuring that this vital project is brought to completion and fully expect to complete construction of the pipeline without any additional rerouting in and around Lake Oahe. Nothing [the Obama] Administration has done today changes that in any way.” Whether or not the company would opt to blatantly break federal law, continue the drilling, and pay a daily fine, was unclear at the time, as it is to me still, at the time of this writing. Nevertheless, the decision marked a significant victory for Standing Rock.

That night, as the wind gusts of up to 40 mph battered our small canvas tent, the message from the waters were not lost on me. Water is the universal solvent, the one into which all else dissolves. It is in this way, the great unifier, as it is one body that moves in many forms on, within, and above this earth. This understanding, while rooted in the physical, extends to the spiritual. In many traditions, whether in the tradition of the peacemaker, or simply in the tears that pour from our body when we truly forgive, water is a source of forgiveness and condolence. On this day, at almost exactly the same moment as veterans apologized to the Lakota at the casino down the road, the water responded with all her fierce gentleness, to those in the marching crowd, few though they may have been, who still sought conflict, by turning them toward peace.

For some with whom I spoke, this influx of white men, veterans or otherwise, felt to them like overt colonization all over again. The camp resources were stretched a bit thin, cross-cultural protocols were misunderstood, and what had begun and has always been an Indigenous-led movement, began to focus on the newcomers.

And yet, with all of this complexity, the beauty of the moment is not to be missed. That 2,500 of the thousands of veterans who wanted to come in support of Standing Rock, stood, side by side with Native Americans, in opposition to the military-industrial complex that has been sending young people abroad to die for resources, including oil, for decades upon decades, is a tremendous victory in and of itself. I know that my own relationship to veterans has been deeply impacted, as have the lives of many at the camps, including the veterans themselves, by such a moment in history.

But, as they tend to do, this blizzard kept coming, and many veterans and others began to leave the camp, even as early as the evening of December 5th. This cold pocket at the banks of the Missouri, where winter temperatures regularly drop below -40 degrees Fahrenheit, was sending people home. As people left the camp, many were stranded. Interstate 94, the major road through North Dakota, was shut down across more than half the state. Two emergency shelters opened up nearby, including the casino. There was a “no-travel advisory” issued for nearly the entire state. The following day, as Jiordi and I began our pre-planned departure home, the sides of the road were strewn with stranded and overturned vehicles.

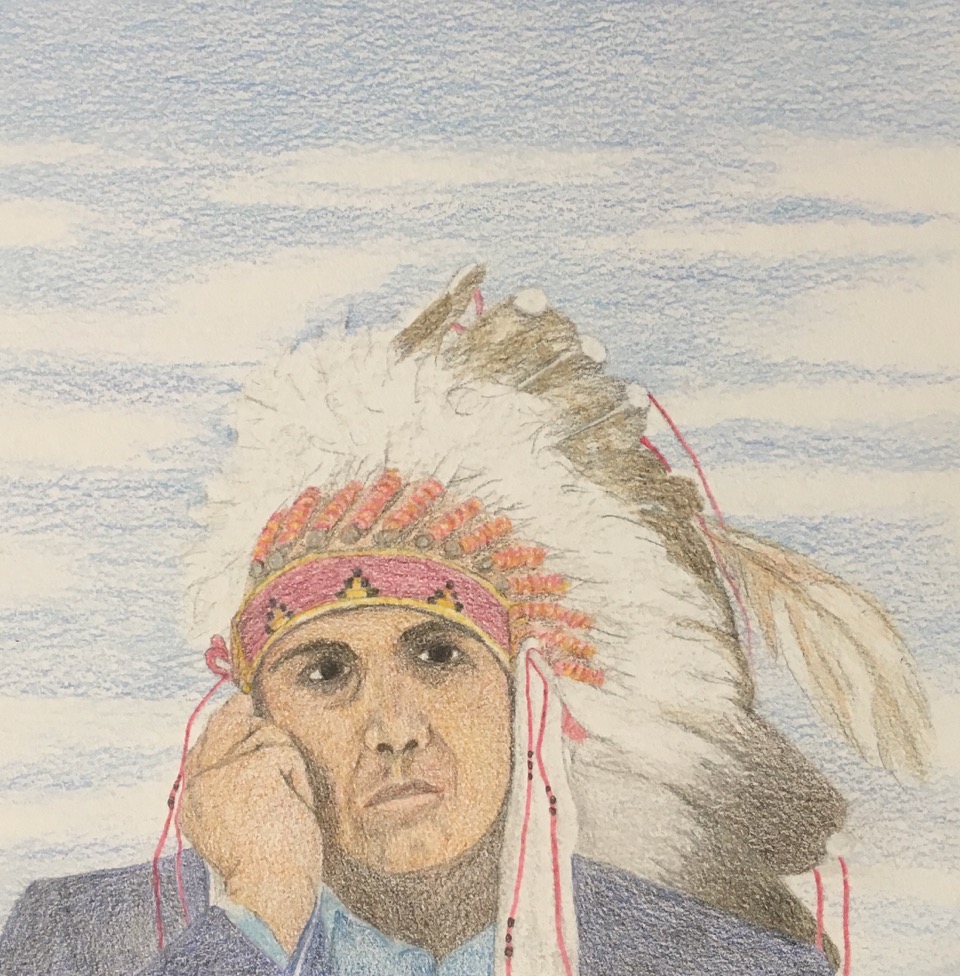

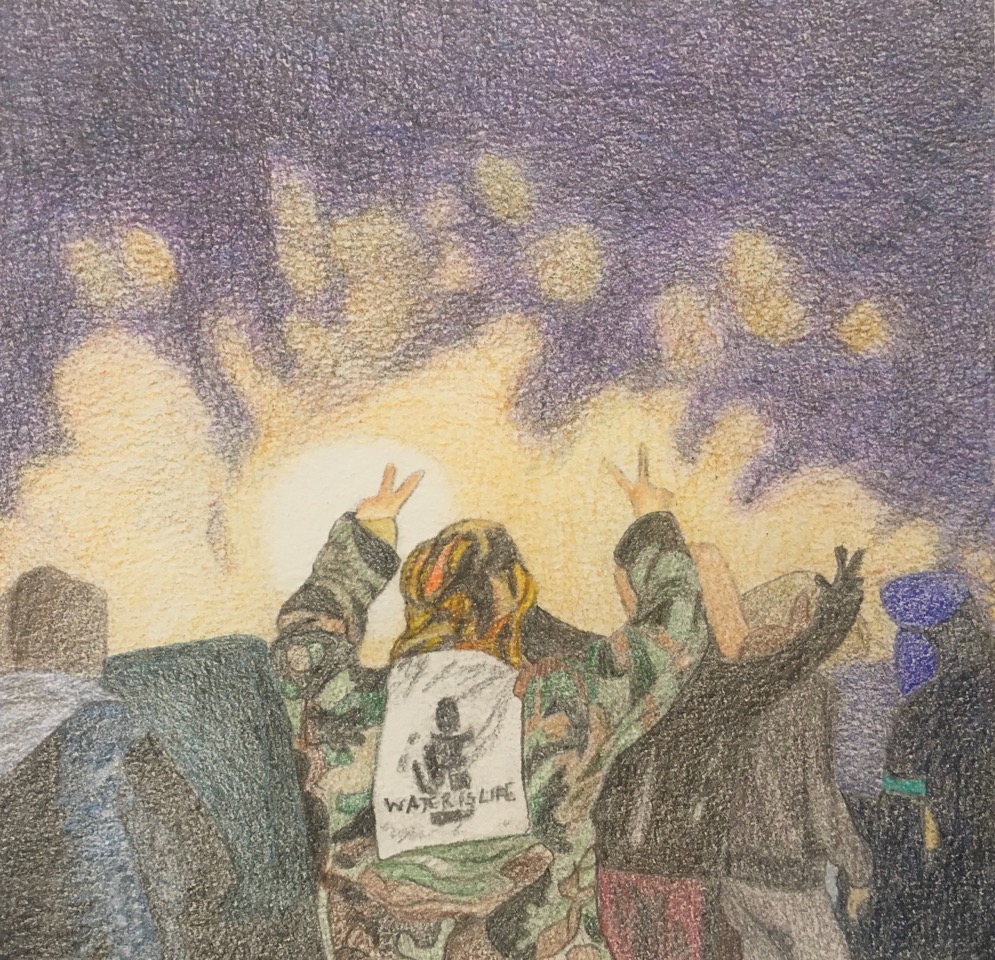

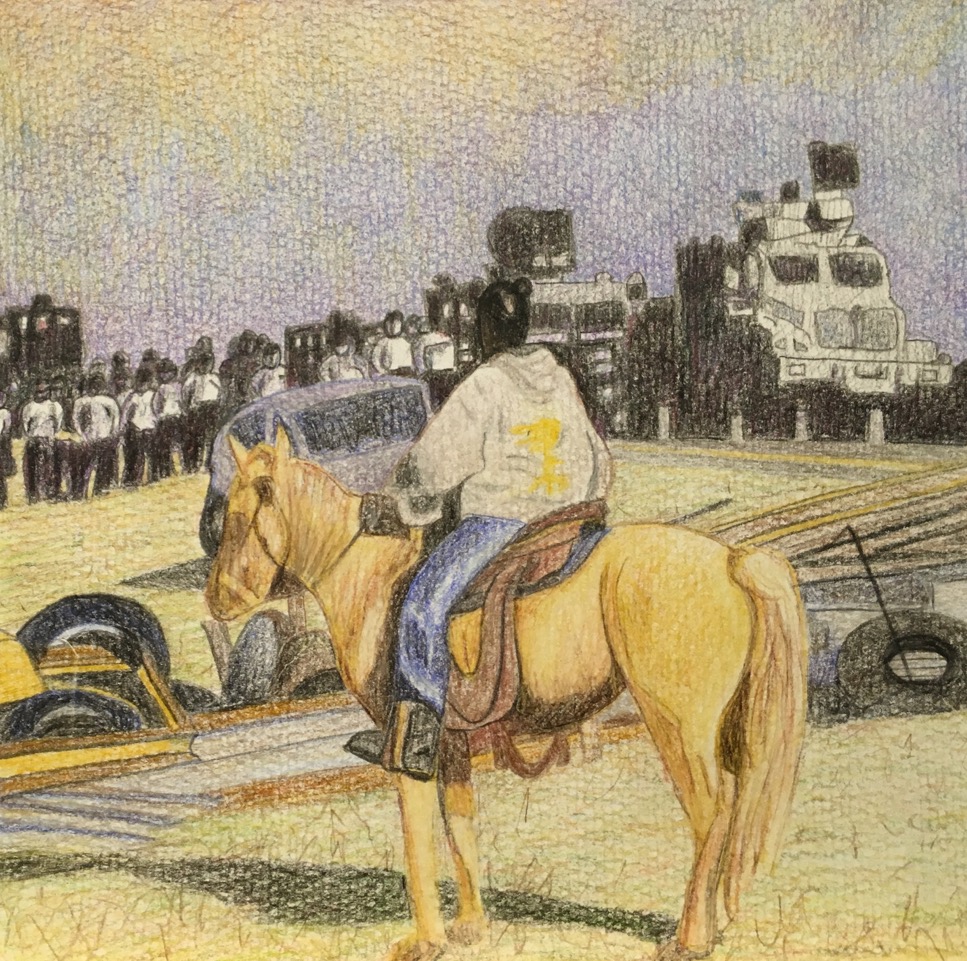

Original Artwork by Chip Romer: Each piece in the series is accompanied by original drawings by Chip Romer, the Executive Director of Credo High School in Rohnert Park, where Brendan currently teaches. In the fall, when Brendan shared with the administration that he planned to go to Standing Rock, he assumed that he would have to quit his job. Instead, they asked him to go as an ambassador for the school. The drawings are part of a series that Chip began while Brendan was at Standing Rock. They are a mediation, a reflection, and a prayer. The series is called, “Pictures of Resistance.” They are being shown publicly here for the first time, alongside Brendan’s writing.

Header image via Dark Sevier