In the 1988 comedy Working Girl, Tess (played by Melanie Griffith), sporting the requisite teased hair and shoulder pads, works as a secretary for Katherine (Sigourney Weaver), who soon into the film steals one of Tess’s ideas and passes it off as her own. By the end, Katherine has been ousted — the villainous harridan defeated — and Tess, newly promoted to Katherine’s position, earns her own secretary. The final scene finds Tess instructing this newly appointed female underling to abandon conventions of deference. Instead, they will collaborate as colleagues. The movie has other dramatic plotlines, but this finale establishes the film’s message as one of working women solidarity: out with the severe lady bosses, in with the compassionate mentors.

That was 30 years ago. But somehow, the prototype of the malicious, self-serving female overseer has prevailed, from The Devil Wears Prada to TV Land’s Younger. Even as onscreen workplaces become more gender-balanced, it is unusual to see women under the supportive tutelage of other women. The Bold Type, the recently-renewed series on Freeform, has deliberately and overtly shattered the ice lady paradigm: a group of ambitious young women find themselves under the benevolent eye of Jacqueline, the tough but constructive Editor-in-Chief of Scarlet, the lifestyle magazine where they all work.

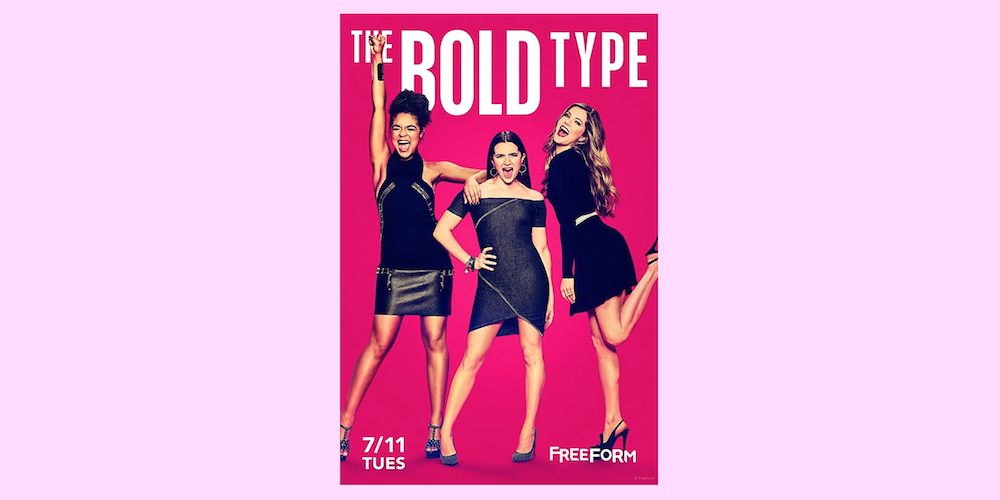

Strutting similar grounds as the ‘80s “career girls” of Working Girl and, of course, the ‘90s feminist third-wavers of Sex and the City, the three leading women of The Bold Type are best friends in their mid-twenties navigating work, friendship, and dating in the big city. Except this time, they all work at Scarlet (a Cosmopolitan stand-in) on separate teams: Jane (Katie Stevens) is a writer, Sutton (Meghann Fahy), a fashion assistant, and Kat (Aisha Dee), the social media manager.

Often written off as girly pulp, The Bold Type has nonetheless developed a certain popularity among its target female millennial viewership. The appeal is understandable; the storylines pivot on issues of identity — gender, class, sexual orientation — that are particularly impactful for younger generations. The show also radiates a go-girl vitality, amplified by the pop music soundscape and clever dialogue. Because their camaraderie extends outside the workplace, the three friends are able to harmonize their individualistic career drives with a sense of team spirit and mutual support. As a result, each episode succeeds in arousing an energy that is genuinely, if flimsily, unifying and empowering — like Hailee Steinfeld’s pop anthem “Love Myself” or a “The Future is Female” tank top.

Realism is lacking in certain respects — the hair and clothing on all of the characters are as flawless and lavish as you’d find in any Gossip Girl episode — but the show’s depiction of working at a publication is actually more accurate than most. There are discussions about balancing stories of substance (political op-eds) and ones that get the most clicks (getting a butt facial), what keywords are best for SEO and social media, how to find a story angle, how to perfect a pitch. The series title is, of course, a double entendre, but it demonstrates the crucial role that journalism plays in the women’s lives.

Which brings us to the show’s most radical character: the magazine’s Editor in Chief, Jacqueline, played by small screen staple Melora Hardin. Overseeing the work of each of the three women, Jacqueline commands respect and expects excellent output while acting as a kind of mother hen to the threesome. Though she has her own giant, glass-paned office, Jacqueline is most often seen stomping the floors of Scarlet in her stilettos supervising the daily mayhem as she ticks off to-do items to her high-strung male assistant trailing behind.

Like any adept employer, Jacqueline maintains a balance of sympathy and rigor, dialing up one or the other as needed. She’s also, like Meryl Streep’s Miranda Priestly, the top dog at a leading lifestyle magazine, and though she has little of Miranda’s ruthlessness, Jacqueline does prove equally chic, savvy, and tireless. She can be bossy, but less like an actual boss and more like a professor or parent. She has a radar for the distinct ways in which Jane, Sutton, and Kat operate, and with that insight seeks to push them, guide them, and impart her own knowledge upon them. In other words, Jacqueline’s no devil, but she’s not really an angel either. She’s the mentor who wears Prada.

With Jane, Jacqueline takes on the most overtly maternal role. At the series start, Jacqueline has just fulfilled Jane’s lifelong dream by promoting her to staff writer, the role in which Jacqueline herself started out. The most idealistic and ingenuous of the bunch (her nickname isn’t “Tiny Jane” only because she’s short), Jane grew obsessed with Scarlet when she was young after losing her mother to breast cancer. The magazine became Jane’s proxy matriarch, and now with Scarlet as her workplace and Jacqueline as her editor, Jane has managed to make the figurative relationship literal.

In a pivotal scene, Jacqueline invites Jane to her apartment after Jane publicly explodes at her in the office. The fight occurred because Jacqueline was pushing Jane to write about BRCA testing for young women, though unbeknownst to Jacqueline, Jane’s mother had been BRCA-positive. Arriving at Jacqueline’s apartment, Jane thinks she’s about to get fired. Instead, she is greeted by a fluffy, white dog alongside Jacqueline’s husband, who welcomes Jane in with the friendliest British accent you can imagine. Seeing Jacqueline outside of work — as a real person with an apartment, family, pet, Moroccan rugs — leaves Jane dumbfounded. Slowly, as Jacqueline tells Jane about her children, her cello lessons, and her Cambodian cooking hobby, the true incentive for summoning Jane becomes clear: she knows that sharing her personal life will help Jane grow more comfortable being vulnerable not only with Jacqueline, but also in her writing.

The centrality of Scarlet in Jane, Sutton, and Kat’s lives underscores the importance of Jacqueline’s affection. Days and many nights are spent in the Scarlet offices, working or just drinking wine and hanging out. When they need to gab in private, the friends retreat to the extravagant fashion closet — an intimate room cluttered with thousands of dollars worth of apparel and jewelry. Kat and Sutton may be more clear-headed than Jane about their relationship to the magazine and may require less hand-holding from Jacqueline, but, cloying as it may seem, Scarlet is still their home.

This cutesiness — the seeming cliché — is calculated. The extremity of Jacqueline’s protective, instructive nature highlights the actual lack of this type of female mentorship onscreen, not to mention in real life. As I and many other watchers of The Bold Type are sorely aware, there still exists an entrenched sense of competition among women in work environments, presumably due to our understanding that there may be a paucity of jobs available to us at any given company. It’s inexpedient to forge female work friendships, we are taught to believe, if there’s only room for one woman at the table. Characters like Jacqueline are rare and valuable, because they teach women that helping one another isn’t dangerous; it’s fruitful and rewarding.

And, though the showrunners couldn’t have known it during development (but perhaps not coincidental to the show’s renewal), The Bold Type has arrived at an especially emboldening time for women in the workplace. Misconduct magnates are toppling at record pace, and in their wake, power matrixes are shifting to accommodate fairer distributions of authority. As we continue to question the types of workplace relationships we want to foster, The Bold Type will be a valuable asset for any working girl.