An effective teacher ensures that all students meet high standards while also responding to their needs as individuals. That’s a tall order for any educator, even taller when your students have had limited schooling. And work full time. And support families. And are learning English.

You see, all of my students are immigrants.

I’m an English teacher at an alternative public high school for adults, just miles from our nation’s capital. I teach students from around the world, but the majority are young adults from Central America. My students have fled communities overridden with violence, torn apart by economic devastation, or lacking in opportunities. Many have suffered personal or family trauma. Because of these reasons and more, they have made the difficult and desperate decision to leave their family, culture, and language behind to face an uncertain future in a new country.

If you’re at all familiar with the stories of immigrants from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, among others, you know they range from inspiring to terrifying. I hear these stories first-hand as my students struggle to shape their memories into meaningful sentences and paragraphs. What starts out as a simple grammar exercise often turns into an outlet for regret or grief. We roll with that in my line of work.

After the 2016 election, my students expressed the same fears that many of us Americans did, though theirs were far more practical than philosophical in nature. Their futures and families are quite literally in jeopardy. As a teacher, I can’t take a political stance in the classroom. But I can express empathy and model inclusiveness and respect for all. That’s just being a decent human being.

I can also craft an entire unit around researching the accomplishments of civil rights leaders throughout history. Seems like a timely topic.

For this unit, I provided my students with a list of men and women in the U.S. and around the world who have worked for equality by speaking out against injustice and organizing for change.

One student researched Gandhi’s use of passive resistance. Another read about Rosa Parks’s act of civil disobedience. One young woman learned about the significance of Angela Davis’s hairstyle while her friend was moved by Malala Yousafzai’s story of survival and heroism.

We studied terms like boycott, hunger strike, and collective bargaining while practicing skills like note-taking, citing sources, and delivering oral presentations. The entire unit was, of course, aligned with the required educational standards. And if my students walked away with a new sense of empowerment, then I won’t say I’m sorry for it.

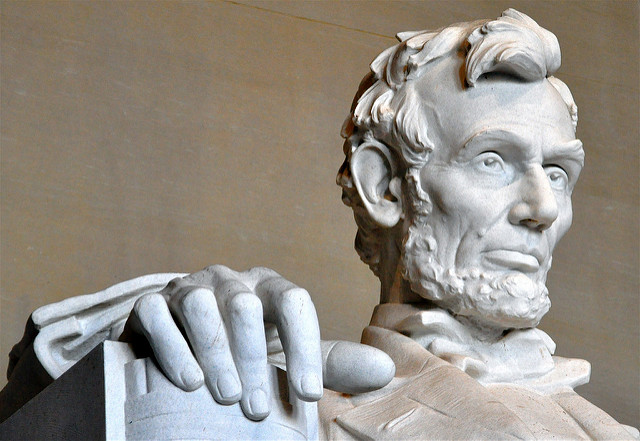

At the beginning of the unit, a student I’ll call Miguel asked me if he could research Lincoln. I debated whether Abe belonged on the same list as Cesar Chavez and Nelson Mandela. He was important, of course, but I really wanted to focus on seemingly powerless individuals who fought for justice and equality. But then I figured, if Miguel had a genuine interest in a significant historical figure, allowing him to pursue it might keep him engaged in school.

Miguel is a bright, curious young man, but he has major issues with attendance. He’ll be a model student for weeks on end, sitting in the front row, correctly answering every question about independent clauses or Latin word roots. Then he’ll disappear for days or weeks on end, leaving gaping holes in my grade book.

Miguel, like most of my students, is exhausted and overwhelmed. In addition to being a full-time student, he works as a food runner at a local Mexican restaurant, often up to 60 hours a week. At 22 years old, he has been working full-time for over a decade. I know this because of an essay he wrote last semester when I helped him organize key events and expand on them with supporting details.

Miguel wrote that he had dropped out of school at 11 years old because his family couldn’t afford tuition for each of their five children. He “traded his school books for a machete and went to work at a farm” (his words) so his siblings could continue in school. As a teenager, he moved to the U.S. because he knew he could earn more, help them more. Now, several years later, he is supporting his family back home, including a brother who is the first to attend college.

Miguel also has a five-year-old daughter he supports. I had been teaching him a year before he shared that. With students like Miguel, young men with tough exteriors and troubled pasts, it takes time to build trust. During our first semester together, I had commented on some beautiful doodles in his notebook, which led to a discussion about his love of art. He pointed out which of his tattoos he had designed himself, including a rosary that wraps around his left wrist and mixes with a series of horizontal scars. I complimented the rosary and said nothing about the scars.

Now, a year later, he often works personal details into his writing. We also discuss the library books he reads to his daughter, books in English and Spanish. Like many of his classmates, Miguel isn’t satisfied with just getting by. There’s a quiet drive for something more, and I suspect fatherhood has something to do with that, though he hasn’t explicitly said so.

Hoping to keep Miguel engaged and attending school, I told him that doing his project on Lincoln would be just fine.

A few days later, I checked in with him as he was doing his research. He had all of the basics about Lincoln’s early life and start in politics. He had a point or two about being president during the Civil War (a war most of my students only learn about once they enroll in our school), but he hadn’t mentioned the Gettysburg Address. We looked it up together, and to provide context, I pulled out my laminated U.S. map.

“See this part here?” I asked, pointing to the southern states. “And this part here?” I pointed to the northern ones. I gave him a very condensed history lesson on the economic and cultural differences between the two regions along with the major causes of the war. I explained that Gettysburg came late in the war and was one of the bloodiest battles.

“Sometimes these battles were literally brother against brother. And these soldiers were young, many even younger than you.”

Nothing about this shocked my student, already world-weary beyond his 22 years. In fact, he had shown me a bullet scar in his ankle just the month before.

“You know how when people in a family fight, no one really wins? That’s how our country was feeling after Gettysburg. In pain. Divided,” I explained. “Lincoln was trying to unite us as a nation, but many Americans were afraid that it was too late.”

As I was talking, I had an eerie feeling that these words were as relevant as ever. At this moment, we are again divided as a nation. We are divided over the mere presence of the population I teach, but our differences certainly expand beyond our views on immigration. Family members have stopped speaking to each other over politics. We are looking at our neighbors, friends, and relatives in a new light based on where their allegiances lie. We debate our national security priorities. We argue over whose lives actually matter. As my own extended family plans its next reunion, I also wonder if too much damage has been done.

Brother against brother.

I thought of Lincoln standing on the very ground where so much American blood was shed, dedicating Gettysburg as the final resting place for those who fought to keep us united as a nation.

You all know the beginning of the speech: Four score and seven years ago. But it’s the last part that moved me that day, reading along with Miguel:

…we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, and for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Those words outline Lincoln’s vision for our nation, but I wonder now if this vision is still possible. With every CNN alert and reactive tweet, I feel it slipping away.

I have read various perspectives on Lincoln’s presidency and his evolving position on slavery. Then there’s the view that the Emancipation Proclamation didn’t free a single slave when you remember that the Confederacy didn’t consider him their president at the time. Also, the union Lincoln was trying so hard to preserve wouldn’t allow for the full participation of women or people of color for years to come. The true story of Lincoln, like most of our American stories, is contradictory and complicated. Also, that doesn’t really matter to me right now.

There’s a time for critical thinking, and there’s a time for myths.

What serves me now, as I feel my country being torn apart by its differences, is the myth of Lincoln as the savior of the Union, the myth of a man from humble beginnings who ascended to the highest office in the land. This is the myth that also serves Miguel, coming from his own humble beginnings and striving for a better life.

Miguel already knows the version of America that slams its door in the faces of newcomers while claiming to be the land of opportunity, but how useful is that version, really? Accepting reality sure wouldn’t have helped my own grandfather when he arrived here from Ireland nearly a century ago. He had limited education, almost no money, and had already been in jail. He was not yet 20. I see the realization of my grandfather’s dream in the cherished family photograph of him, by then mayor of his town in New Hampshire, standing with John F. Kennedy at a campaign event.

In my family’s history, my grandfather is a charming, conquering hero, though in reality he was complicated and flawed, just like me, Miguel, and Abraham Lincoln. Complicated and flawed like the United States. I’ll take the myth.

After my students wrapped up their presentations, I asked them to look for the common threads that connected many of the people they’d researched. In small groups, they generated ideas like:

They didn’t use violence.

The spoke up for what was right.

They spoke up when things were wrong.

They were individuals who made a difference.

They didn’t work alone. They were organized.

They didn’t give up. Big changes take a long time.

Yes, they do, I agreed. And we can’t give up, either.

After our unit on civil rights leaders was finished, our class moved onto more traditional curriculum. Irregular verbs. Persuasive essays. The elements of a short story, including the various types of conflicts. Man vs. himself. Man vs. man. Brother against brother. I find it all loaded with meaning right now, but I’ll leave my students to make their own connections. An effective teacher doesn’t tell her students what to think, but how to think, and in my case, how to express those thoughts in a new language. I can help my students find their voices in English, but it’s up to them to speak for themselves.

In the meantime, we will have to carry on as a nation. We will go to work, raise families, try to tolerate each other’s differences. We will keep believing in the myth that America is the land of opportunity in which all men are created equal. And Miguel and I — and I hope you, too — will not stop until we make it so.