On Thursday, March 14, 2019, the Viking Sky cruise ship embarked from Bergen, Norway with the intention of stopping by several Norwegian towns over the next 12 days on the way to London. By late Friday, however, the ship had sailed into a massive bomb cyclone that flooded parts of the ship with 60-foot waves and knocked out the ship’s engines, sending it adrift toward the rocky Norwegian coast.

Travel writer Chaney Kwak was on this cruise on assignment. As the ship’s 1,400 passengers awaited rescue by helicopter, Kwak took notes on this disaster in the making, while contemplating the meaning of other storms in his personal life, which included a mother battling cancer and a two-decades-long romantic relationship also heading for the rocks.

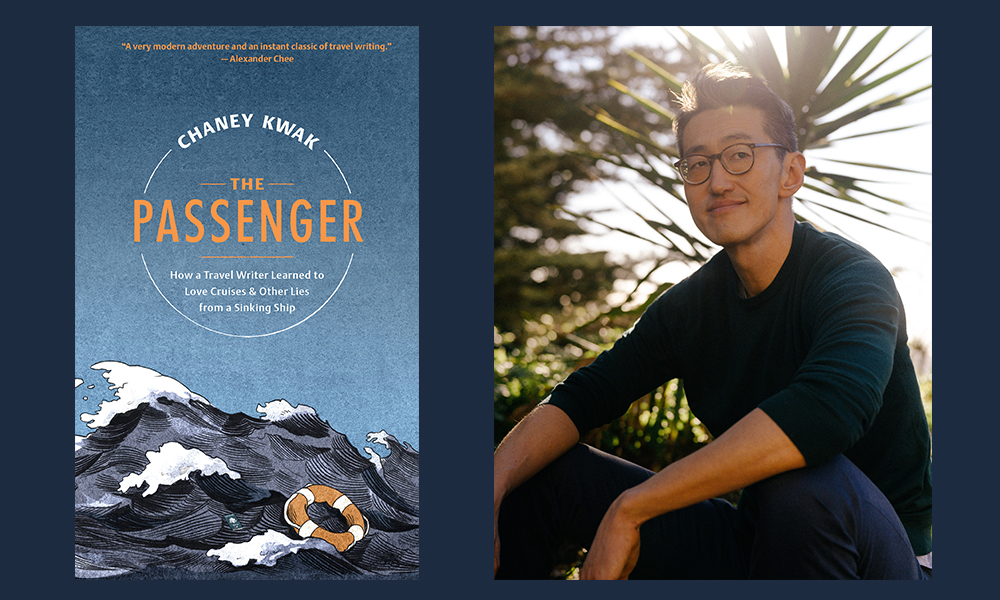

The Passenger: How a Travel Writer Learned to Love Cruises & Other Lies from a Sinking Ship moves effortlessly between Kwak’s droll observations, after-the-fact reportage, and heartfelt passages of romantic despair. He and I exchanged emails about the genesis of the book, what it was like to be part of an unfurling disaster on social media, and whether a truly authentic travel experience is possible.

¤

LELAND CHEUK: How long after this cruise did you know that you had to write a book about it? Did you know during this calamity that if you got out of this alive, you’d have to do it?

CHANEY KWAK: Honestly, I wasn’t convinced The Passenger was a book even when my editor, Josh Bodwell at Godine, tried to tell me so. I thought it was a long-form magazine article, but he convinced me to go deeper after seeing my very old draft, which was meant to be shopped around to magazines. During the pandemic, the manuscript’s word count tripled to its current length, which made it a slim book. Several readers have reached out to tell me they read it in one sitting, which is the greatest compliment. During the incident, I did take lots of notes, but I didn’t really have an end goal in mind. The 2020 lockdown really crystalized what the story was about: not necessarily about a literal cruise ship going down, but about drifting off course in life and trying to correct the course, all the while being locked down in confinement.

I found your observations about social media particularly salient and original: that “Gut feelings receive equal airtime to basic facts — such as, say, the Earth being round or a vaccine preventing polio.” And then I thought about what it must have been like to be on that cruise, with all that chatter and a lack of solid information. Did you feel like you were living a real-life version of social media on that ship? Is social media just a doomed cruise too?

During the ordeal, when the ship lost its engines but was close enough to the dangerously rocky coast to have cell signal, I was aghast but also morbidly amused by how we became the fodder for social media-based reality TV. My sister’s 12-year-old Aria brilliantly calls the internet “the Ali Baba cave of dank memes and wrongish humor,” and I think it applies to social media in particular. It’s a dank echo chamber.

When you’re in the midst of a disaster in the making, it’s pretty dismaying to become the butt of said wrongish humor. Of course, it’s not all black and white. Social media does connect humans, and can mobilize society — but in what direction, that’s up to the very people who are using it. Ultimately, I think tech companies know how to cater to our pathological narcissism and basest addictions; what we make of social media is just a reflection of who humans are today, I’m afraid.

There are a number of personal crises that are happening off-screen (or off the boat, so to speak) while you’re on this cruise. Namely, the unwinding of a long-term relationship and your mother recovering from breast cancer. You write, “Why is it that those in crises must often take the burden of soothing others?” Would you say that being in these crises helped you distill and define your concept of love?

I’ve wrestled with this question, and I still have no answer. I think much smarter writers have tried to answer what love is, and I have nothing original or coherent to add to that discussion.

Didn’t Faulkner say, “You don’t love because: you love despite; not for the virtues, but despite the faults?” The problem is, when do those faults become insurmountable — that’s the question I’m more curious about. When is it over?

You make some interesting observations about the uncomfortable racial and class dynamics on cruises as exemplified by mostly pale-skinned passengers and the brown piles workers. And of course, it’s a Viking cruise, and we know what the Vikings went around doing—

Ha! That’s hilarious. I honestly never connected the dots between the brand’s sophisticated image with the reality of marauding Vikings, leaving a trail of destruction. Well, let me ask you this. What’s an authentic experience in your town?

I’d say standing in line for half an hour or more for artisanal donuts or tacos that you learn about only on Instagram.

And I hate waiting in line. Let’s say most locals love going to the strip mall, waiting in line, and getting takeout from a chain. That place may be devoid of a single tourist, but it still doesn’t sound like a local experience I want if I’m visiting the country for a few days; I’d rather go to a kitschy restaurant serving old-fashioned food and playing traditional music.

Of course, the other extreme is when the travel industry self-tokenizes and serves the most caricature-like static version of the local traditions to only foreigners.

The point is this: in our social media-driven world, travelers have become obsessed with presenting authenticity to the world, but that’s just drag — tourists getting into local drag. It’s performative. So how do you even define authenticity if it’s for an audience back home?

I understand the impulse to avoid tourist traps — nobody likes to be taken advantage of — but I think every experience that a tourist has is an authentically touristy experience — and there’s nothing wrong with that. I love being a tourist. The moment you refute the very fact that you’re an interloper is when your experience becomes fake.

You portray so well the fog of being in a long-term partnership as “this queer mix of muscle memory and personal history that binds two people together, despite their best efforts.” What would your advice be to those who are deep in that type of fog now?

Drink lots of water and try to get some sleep? I don’t know, I don’t have any advice. This much, I know: People will tell you to do all sorts of things, but you will go at your own pace. You can only do what you’re ready to do. I spent years in inertia, but maybe that’s just what I needed to get going again. The act of writing The Passenger was a crucial part of that process. I think you’ll agree that the latter part of the book, in some ways, describes the changes that take place just as the book is unfolding.

You say that what you want most is to “dream again.” That struck me as universal as one moves from being striving and young to middle-aged, when you’ve probably achieved just about everything you’ve set out to do as a young person, and there’s still an empty feeling of “What’s next?” Have you figured out how to dream again?

It’s an ongoing struggle. We move our goalposts constantly, and maybe that’s not a bad thing. Does dreaming involve moving the goalpost even farther away? Or is it about dismantling one altogether and accepting the meandering nature of life?

It’s an open-ended question for me. I used to believe I had it all figured out. Now I have no idea what’s ahead two months from today. Maybe it sounds like a nightmare to some, but it’s dreaming all the same.

Top image of Chaney Kwak courtesy of Michael Baca.