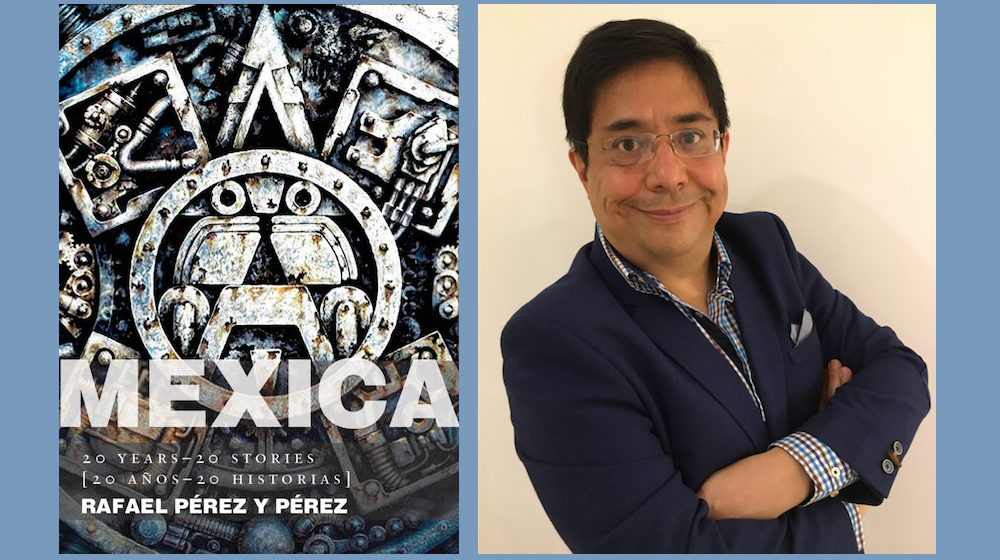

How might legacies of the 15th-century Mexica empire manifest in today’s creative computing? How might creative computing transform the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves, conjuring broader cross-cultural understanding without consolidating the types of cultural bias appearing in present-day commercial AI applications? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Rafael Pérez y Pérez. This present conversation (transcribed by Christopher Raguz) focuses on Pérez y Pérez’s Mexica: 20 Years–20 Stories [20 años–20 historias]. Pérez y Pérez specializes in artificial intelligence and computational creativity, particularly in automatic narrative generation. He founded the Interdisciplinary Group on Computational Creativity (which develops models for plot generation, plot evaluation, representations of social norms, visual narratives, and creative problem solving), and chairs the Association for Computational Creativity (which organizes the annual International Conference on Computational Creativity). He is a professor at Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana at Cuajimalpa, México City.

¤

ANDY FITCH: I’ve seen you describe MEXICA as a “system that represents the creative process of writing.” And the back of your book describes MEXICA as a computer program. What is your most direct way to answer the questions: “What is MEXICA? What does MEXICA do?”

RAFAEL PEREZ Y PEREZ: I often introduce MEXICA as a computer system that generates narratives. And when I want to give a little more detail, I describe MEXICA as giving us useful information for understanding human characteristics of how we tell narratives. MEXICA both represents and allows us to study some of the processes that we ourselves follow when we narrate something.

Your afterword outlines how you “feed” MEXICA. Could a different meal for MEXICA, or a differently designed MEXICA, examine and invent not plot so much as character, setting, tone, linguistic nuance and play? Or does something about plot’s logical (or at least partially logical) operations make plot the best fit for MEXICA?

One of the hardest tasks for computer models of creative writing is to generate coherent sequences of actions without employing predefined story structures created by the system’s designer. So from the beginning I designed MEXICA specifically as a plot generator, in order to contribute to tackling this problem. I employ plots, written by humans, to “feed” the system and to build its knowledge base — and then, using such knowledge, MEXICA generates its own novel plots.

When I first created MEXICA, I wanted to research how writers think about writing. I wanted to investigate how writers read in order to learn about the world, but also how they study technical aspects of narrative. So I developed a simple mechanism (following a rigid character-action-character format) in order to feed MEXICA stories that it could then use to learn about this world of stories. MEXICA doesn’t focus on localized linguistic functions. Its goal is to manipulate plot structures that we normally use to tell stories. And anybody can provide MEXICA stories, so long as the person follows this rigid format. If you help by giving me stories to use, then MEXICA will now have that pool of knowledge to generate new narratives. That’s also how we often get information about circumstances, and react to those circumstances.

MEXICA then generates novel sequences designed to be both interesting and coherent. MEXICA writes stories basically following this same character-action-character sequence: “The princess went to the forest. The jaguar knight captured the princess…” Finally, the program substitutes more elaborate predefined descriptions for such sequences: “That sunny morning the princess decided to walk to the beautiful forest.” That’s how this system processes and expresses narrative.

So my future research will involve collecting narratives from many different people of all different ages, countries, ethnicities, and so on. I’ll feed MEXICA and examine differences in the types of stories MEXICA generates depending on which groups provide the information. MEXICA primarily learns how to react to certain narrative situations — not to all the other aspects related to literary language. It shows us how human narratives generate and manipulate certain circumstances in order to achieve coherence, and why certain plot aspects work best for that.

In terms of MEXICA interacting with both its content-providers and its audiences, and in terms of MEXICA the book celebrating MEXICA the computer system’s first 20 years of operation, could you describe a bit MEXICA’s initial versions, its earliest stories, your debut presentations of them, the first responses you received?

I designed this system’s first version during my PhD studies. In those days, MEXICA only produced stories in the rigid format that I have already described. But soon it became evident to me that readers required more elaborate descriptions. So I decided to incorporate the possibility of adding those predefined texts I’ve mentioned, which allow for generating more human-like narratives. In the same way, the cognitive model behind this system back then was much simpler than it is now.

After finishing my PhD, when I was looking for a job, I had to give a presentation for the National Polytechnic Institute in México City. I remember that this particular audience seemed fairly incredulous. During this presentation, a Russian professor mentioned that in Russia many people designed these types of programs. I sensed him trying to diminish MEXICA, and I answered him: “I’d be very happy to meet these people!”

Of course people in the computer-science community can come across as very closed-minded, and only comfortable with very well-established research topics. Still, I did get hired at the National University (UNAM) by some researchers interested in my work. But the rest of the professors still didn’t take the MEXICA program seriously. They wanted me to do something more “normal.” So for five years I faced this skepticism and resistance, and after the fifth year they told me they wouldn’t renew my contract. Luckily I found some other professors really open to learning more about MEXICA. When I finally got a job at the Autonomous Metropolitan University (UAM), these new colleagues were excited to hire me. So yes, the beginning was complicated. Today, with MEXICA receiving more international recognition, I don’t face as much professional criticism.

Here could you also place your work with MEXICA in the broader context of your work with the Association for Computational Creativity, and with the Interdisciplinary Group on Computational Creativity? D. Fox Harrell’s semi-fictionalizing preface, for example, describes the “grizzled leader of the Association for Computational Creativity” passionately advocating not only MEXICA but “TALE-SPIN, Minstrel, BRUTUS, Curveship.” Could you describe how MEXICA relates to some of those “like offspring”? Or could you sketch some of the main research / creative questions from the field of creative computing that you see MEXICA also asking?

The Association for Computational Creativity seeks to promote this emerging and passionate field. In that way, MEXICA, and especially the Mexica: 20 Years–20 Stories [20 años–20 historias] book publication, have been very useful.

Now in computational creativity, we have a continuum with two poles, emphasizing the computational and the cognitive-social. The more mathematical (computational) approach seeks to develop pieces that can have an impact on a large audience — emphasizing the product rather than the details of the process. On the other (cognitive-social) side of this continuum, some of us want to contribute to a better understanding of the creative process. We want to produce new knowledge about creativity.

So as you can see, computational creativity pursues two very different goals. I recently presented a paper titled “Computational Creativity Continuum” where I developed these ideas. I see those systems you just mentioned falling more on this continuum’s left side, based on conventional artificial-intelligence techniques that I consider more mechanical, more focused on achieving specific goals. I would put MEXICA closer to this continuum’s right side. I try to use MEXICA to gain knowledge about how creativity functions. With MEXICA, I especially want to generate answers, through different ways of representing that knowledge.

But I also should stress the importance of both approaches in our field. We are studying a phenomenon that we hardly understand. We need to employ all available tools to gain insights about how creativity works.

Creative computing’s emphasis on cross-cultural inputs also stands out. Harrell’s preface describes this field asking (singing, actually): “Must computers always express the voice of the colonizer — could a computer instead express the voices of sovereign indigenous peoples, the oppressed, and the otherwise underrepresented?” Could you place these particular questions in a broader cultural context in which we see, for instance, AI processes often absorbing racist biases circulating in U.S. culture, and then further entrenching and institutionalizing those biases? Does MEXICA work against such trends?

Well again, I definitely do want MEXICA to absorb many different types of stories from a diverse range of sources. I hypothesize that people’s personal and social histories will strongly influence the narratives MEXICA produces. For example, we have submitted a project proposal which would take us to the south of México, to talk to many indigenous groups who have traveled to other states or to the U.S. and have then come back. These groups have very distinctive narratives showing how they see and understand this broader world, how they live their lives, what happens when they come back. And this proposal would allow us to study and analyze what kinds of complicated narratives that lived experience generates. Here I tell you this because I think MEXICA can help to provide a voice to real people with real experiences, people who don’t have many opportunities to publicly share their stories. Hopefully MEXICA can contribute to sharing many important narratives that we otherwise might never hear expressed.

Now that doesn’t mean I want to reinforce biases. I sure hope not. I consider it very important to watch out for biases, and to stay alert and to improve on the program. MEXICA can explain in detail how each part of a generated narrative gets built, so if we detect any negative biases, we can trace these to their source. This actually might result in a useful tool to fight against that plague of biases. And hopefully constructive feedback, along with continued research into biases both in this system and in society, can help to make MEXICA even better. We need to study these unexpected developments in computer programming, to help us to stay self-reflective and to further open up our minds.

Of course MEXICA’s own name, and then so many cultural references throughout these stories (to Huitzilopochtli, the Tlatelolco market, the Popocatepetl volcano), point very specifically to the Mexica civilization (what many readers in the U.S. might think of as “the Aztecs”). The Mexicas are, as you describe, the ancient inhabitants of the Valley of México. They are certainly indigenous, and also imperial. Their civilization is ancient, but from present-day perspectives, their relatively brief empire might seem less timeless than ephemeral. So the Mexicas’ historical narrative resists some of the patronizing connotations that, say, liberal white North Americans might bring to indigenous peoples as pure, perennial, passive victims. Could you describe the distinctly Mexica or Mexican aspects of MEXICA, and why you consider these aspects crucial to the project?

My family always encouraged me to deeply appreciate our Mexican culture. In fact my aunt traveled around the world singing Mexican music even for presidents and other heads of state. I have a photograph of her with Lyndon Johnson, because my mother accompanied my aunt on that occasion. John Kennedy was still president, but nevertheless!

So Mexican culture always has been a really important centerpiece of my identity. I come from a specific culture, and I consider that an important autobiographical fact. My PhD studies focused on computers, but I also studied pre-Hispanic culture quite extensively, and I still love to do that. And artificial intelligence actually was perfect for me, because I love psychology and sociology, and I had these computer skills, and it excited me to mix all of those interests together. Even while getting my PhD in more cognitive and technical skills (not cultural skills), I wanted to include culture in some way, because of its personal importance to me.

“Mexica” was the original name for our people. According to myth, the gods themselves gave the Mexicas this name. The rest of the world knows them as “Aztecs” because, when the Spanish arrived, the Spanish thought the Mexicas came from a mythical land in the north called Aztlan, and thus named them “Aztecs.” Anyway, the point is that I decided to go with the original name — the correct name from that original perspective. I want MEXICA to transmit some aspects of this culture, even if the MEXICA system itself doesn’t recreate specific historical narratives. MEXICA instead works with historical types of characters, and real physical locations. For me it felt necessary to use my technical skills to help the world learn a little bit more about this amazing culture: the culture where I live, the culture where I grew up, where I come from.

Of course the history of the Mexica empire also provides a very powerful narrative. I strongly recommend the novel Aztec, by Gary Jennings, and I do see a lot of clear parallels between the Mexica empire and the U.S.A. And of course the Mexicas did things I disagree with, like conduct human sacrifices, which they believed indispensable to continuing their religious work. I don’t approve of that, but that’s historical fact.

And then, more broadly, when you describe MEXICA as a “tool that contributes to understanding creative writing,” what has MEXICA taught you about plot or narrative? And what has feeding these stories, processing these stories, reading these stories, “authoring” these stories given you for answers to those follow-up questions that Harrell’s preface asks: “what makes a story interesting? What makes a story novel? What makes a story creative — both in its content and as it relates to stories from times of yore?” Or in terms of what Harrell describes as MEXICA’s surprising “coherences and idiosyncrasies,” what are some exciting narrative innovations MEXICA has made that other fiction writers should pick up?

For me, one of MEXICA’s most interesting aspects is that it represents emotional conflicts within and between characters — as its core mechanism for generating a sequence of actions. That’s very difficult. Other systems have created coherent stories more by outlining basic structures of actions. But MEXICA builds its scaffold and constructs its story through internal and emotional conflicts.

MEXICA also has developed a mechanism so that it can read its own stories. Of course narratives have many subjective elements, depending on mood and suspense and other things. So I wanted to develop this computer model as a starting point, again to find out what makes a story interesting — which parts of a story make you reflect, and maybe challenge your own ideas. And MEXICA likewise can actually change its own narrative process based on its reading of itself. It can detect when a story needs more conflict or more coherence. I don’t know in advance whether readers will find a MEXICA narrative interesting, but at least from this cognitive-science and artificial-intelligence perspective, MEXICA’s ability to design coherent dramatic stories is important.

Now, what can other fiction writers get from MEXICA? This computerized storyteller has the potential to challenge our deepest ideas about how we write, about what a narrative is, about the role of stories for individuals and for society. And it’s also a tool for experimenting. A writer who allows herself to get enveloped by MEXICA might gain perspectives on the creative process that she hardly would experience in some other way, and that can provide novel and interesting ideas for innovative narrative approaches.

Well in terms of your own narrative explorations, it interested me here to rethink how coherence actually requires conflict. Or what does it say about MEXICA’s probings into the logics of plot construction that almost every story’s dramatic arc seems premised upon the fundamentally illogical actions of its human characters — with recurring development such as, from Story 16:

“Endlessly the princess reproached herself for her incongruous behavior.

Without thinking about it the jaguar knight charged against the princess”?

MEXICA does operate from the idea that you need a conflict to have a story. You need an introduction, a developing conflict, a climax, and a resolution. Of course a writer could come up with other ways to produce narratives, but MEXICA always employs those specific elements. And MEXICA creates many different kinds of conflicts, which again is what makes MEXICA interesting. One character might both hate and love another character — which makes for a narrative that opens up many possibilities. MEXICA’s narrative mechanisms rest on this multitude of potential outcomes. Emotional conflicts can lead to so many outcomes. MEXICA understands this, and uses these conflicts to make its story better. So I’d even say that a character who starts with an emotional conflict might act consistently, regardless of whether those actions appear contradictory.

And here more specifically, in terms both of explicit and tacit social information processed by MEXICA, how / why has it come about that so many of these stories involve some driving factor of erotic attraction / confusion / resentment mostly (though not always) between men and women — mostly involving some form of conflict, violence, flight? Or could you describe your own emotional experience as you see MEXICA consistently put together such stories?

Let me give a few related answers. First of all, when I started this project, it made sense to include violence because of the Mexicas’ own cultural history. Violence also can grab a reader’s attention. And violence can show both internal and external conflict. Early on, when I had to put a lot of thought into deciding what types of core conflicts would drive these narratives, violence fit well for all of these reasons.

And because both in México and across the world we see so much violence, I do want MEXICA to create different kinds of narratives that take these tensions of real people and make them into something cathartic. But I also think it’s important to include stories that parallel the real violence that our communities face. Here one especially interesting fact about MEXICA is that it still does not have a way to represent the concepts of “we” and “you.” So at the moment, MEXICA still cannot produce narratives that include discrimination towards “others.”

Then in terms of your question’s second part, when this system generates something completely unexpected, something surprising, that does make me emotional. For instance, as far as I know, Mexica culture did not accept homosexual relationships. And I personally like to challenge people to be more open. That motivates me a lot. So I find it moving when gay characters appear in these stories.

Along those lines, I wondered whether MEXICA has “matured” or “progressed” or “developed” in any way over these 20 years, or whether my own narrativizing projections just make me think this happens. It seems significant, for instance, when a rhetorical question gets introduced in Story 4: “The warrior felt betrayed when he learned…the princess and the jaguar knight were in love…. How could they do this to him?” Or it seems potentially constructive when introspective guilt emerges in Story 10 (“The jaguar knight felt guilty for all the things that he had done to the lady…. The jaguar knight was confused and was not sure if what he had done was right”). And then conversely, it seems depressing when slavery arrives in the society of Story 11 (maybe not coincidentally, Story 11 also offers a “bad spirit”). So again, how might the emergence of these more self-reflective (and sometimes more oppressive) circumstances surprise you, and shape your own experience as both creator and reader of MEXICA?

I have been refining MEXICA for the last 20 years. The cognitive-inspired model behind this system, which includes the representation and manipulation of characters’ emotional reactions to progress the story, has undergone profound improvements. As a creator, these features provide important information about how to develop and evaluate a narrative. As a reader, it surprises me how much power such elements can add to these descriptions of events.

I appreciate all those examples you just gave, because they offer new possibilities for narrative development. For instance, I like very much your suggestion of using introspective guilt as a way to modify characters’ behavior. If MEXICA only generated plots which I could predict for its stories, this system wouldn’t really interest me.

And more generally, does examining readers’ experience of MEXICA and of MEXICA also interest you? For example, MEXICA the computer system’s calculations might all take place within the confines of a single story. But most readers of MEXICA the book probably absorb much more than one story per sitting. So what has transferring MEXICA to MEXICA taught you not only about dramatic plot structures, but about readers’ temporal experience of a broader narrative sequence, and / or about various technologies of reading? To what extent does the machinery of codex-book construction (with any story always placed alongside other stories, interacting with each other in ways MEXICA does not control, so that encountering the phrase “the princess” in one context might have quite different meanings for readers depending on where else they have encountered that phrase in other MEXICA stories), or the machinery of paratext (contextual information such as book cover, title, preface, afterword, bibliography, etcetera), or the machinery of translation (here from Spanish to English), seem crucial to the MEXICA project, or seem incidental — just random parts of present-day book circulation?

I’m definitely interested in all those questions. A lot of them have arisen since Counterpath Press published this book. I have learned a lot from readers telling me about their experience. When MEXICA developed its first narratives intended for the book, I asked my wife and my sister what they thought of these stories, and what feedback they had. They actually both got angry sometimes at what they read, or sometimes they found a story confusing. That helped me to realize how differently we experienced these stories. So I decided that MEXICA needed to present certain plot elements and structures more clearly. I think this balance between a normal and an abnormal narrative is very important to MEXICA’s style — which I consider very minimalistic.

And also, like you said, MEXICA still only makes decisions for individual stories — not for a whole book. So when readers sense repetitions (even though MEXICA actually doesn’t repeat the exact same phrases or plot developments), that teaches me a lot about readers’ experiences, and about how to keep improving the system. For some time, one of my goals has been for MEXICA to generate longer stories. But the experience of publishing this book also has interested me in studying how MEXICA can produce several connected and complementary short stories.

You mentioned MEXICA’s minimalist style. I actually thought of minimalist music, with its minimal-event horizons, where you might hear the same note many times, until a very slight change occurs, and this subtle shift suddenly feels like a big deal. By comparison, if MEXICA’s princess has a bad mood for four straight stories, and then in the fifth story feels more ambivalent — even just that muddled mood can register as a significant tonal shift. And those types of structured variations can make MEXICA stories feel quite similar and quite distinct at the same time.

Yes I agree that a small difference can be very interesting for the reader. I want MEXICA’s narrative mechanisms to allow for exploring those kinds of subtle variations. Again, although this book has a minimalistic style, if you read carefully, each story does become very different from the others. Each presents distinct human feelings or situations. For example, one character might fall in love with another, but then a third character will get jealous and want to kill these lovers. You always see a different complex tension play out among these characters.

Though even as these stories always feel quite distinct, I do note at least one consistent current across this whole collection. Why do you always include “The end”? What emotional or algorithmic relation to “The end” do you or does MEXICA have and / or imply — especially, again, in this story collection filled with violence, with wounded characters, with fleeing characters, but almost entirely without death?

That actually happened more as an internal technical decision. Previous versions of MEXICA used to produce tales with unresolved conflicts. They often did not feel coherent to me. So I modified the program to take care of this situation.

In order for a story to end, MEXICA needs to determine that all of its conflicts have been resolved. But the program sometimes has problems working through certain types of conflicts. For instance, as I’ve mentioned, the system automatically detects when one character both hates and loves a second character. This triggers a conflict called “clashing emotions.” That particular conflict gives MEXICA lots of possibilities for developing a narrative. However, a story also could end with the princess, for example, still feeling clashing emotions towards the knight. In that case, MEXICA adds “The end,” again in order to release the tension due to these clashing emotions — so that this narrative can end without unresolved conflicts.

Here again I consider MEXICA’s ability to employ different types of narrative strategies to resolve different types of conflicts one of its most interesting characteristics. For the tension called “potential danger,” for example (triggered when one character hates a second character, with both placed in the same location), MEXICA could release this tension by killing a character, or by separating the characters, with one fleeing far from the other — as a less “dangerous” way to release that tension.

And I’m glad these ancient characters don’t have social-media accounts, because then, even if they ran far away from each other, they might just keep escalating the conflict.

Good point!