What is found in a “found object”? That question, like many questions that have animated postwar American art, was first asked under very different circumstances. A remnant of the prewar European avant-garde, it was most memorably posed by the Surrealist poet and theorist André Breton in his 1937 autobiographical novel, L’Amour fou. Recalling a meandering walk that he had taken with the sculptor Alberto Giacometti through the Marché aux Puces flea market in Paris in the spring of 1934, Breton described how he came upon a large wooden spoon with a distinctive slipper-heel handle. Although otherwise unimpressive, this “found object,” or “objet trouvé,” seized Breton, who purchased it and brought it home, still wondering why it had had such an effect on him. After some time, he realized that his apparent interest in the spoon was only the most recent link in a much longer associative chain that led deep into his unconscious. In a convulsive moment of perception, he recognized that its slipper-heel called to mind a glass sculpture of a slipper that he had asked Giacometti to make for him months earlier but that the sculptor had never delivered. That sculpture was in turn linked to a half-formed phrase, “the Cinderella ashtray,” that had occurred to Breton in a waking dream earlier still. Together, that half-formed phrase and the undelivered sculpture made up yet another composite link that reached even further back, now to Breton’s erotic desire for the “lost object” as such. What had initially been a simple wooden spoon came to symbolize for Breton “a woman unique and unknown.”

Today, this kind of careening backward into personal desire will likely strike many as embarrassing. And yet, the category of the “found object” persists. Although no longer tied to the notion of the unconscious, the sense that everyday objects form a tissue between the obvious and the not so obvious is still with us and has underwritten decades of second looks and double takes. While we no longer feel able to answer with Breton’s confidence, the question — What is found in a “found object”? — remains a compelling one, and Vija Celmins has made a career by letting it linger.

Celmins comes by the question honestly. Latvian-born, Celmins fled her native city of Riga for a refugee camp in southwest Germany in the early 1940s, escaping first Communist and then Nazi occupation before immigrating to the United States in 1948, where she settled in Indianapolis. After studying painting and printmaking in Indiana at the John Herron School of Art, Celmins was awarded a summer fellowship to study at Yale in 1961. There, under the influence of Jack Tworkov who had recently replaced Josef Albers as the school’s driving artistic force, she was exposed to the work of the Abstract Expressionists, who were themselves among the first American inheritors of Surrealism. Based in New York, painters like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning were the beneficiaries of the surge of Surrealists who arrived in the city seeking refuge as war broke out across the continent.

However, the Abstract Expressionists’ inheritance of Surrealism was only partial, and began a process of depersonalization that would distinguish the American reception of Surrealism in general, and of the “found object” in particular, for decades to come. Hardened by the Depression, many of them found the sort of wayward, idiosyncratic passion that Breton celebrated to be dandyish and superficial. Impressed by Surrealism’s other aspects, they resolved to discipline that passion by exchanging their European predecessors’ interest in the individual unconscious of Freud for what they took to be a more sober and more quintessentially American interest in the collective unconscious of Jung. Although they would often access that collective unconscious somewhat contradictorily by way of personal, psychological regressions — as in the case of Jackson Pollock, for example, who struggled to capture the human condition by making mural-sized works in which the processes of the mind would take on form in the tangled skeins of paint that he threw down in his Springs, NY barn — those personal, psychological regressions were countered by another set of impersonal, cultural regressions.

Robert Motherwell, for instance, who was perhaps the most coherent of the Abstract Expressionists, criticized the excessive individualism of the Surrealists. They were, he explained dismissively, “romantic defenders of the individual ego.” In the short-lived but influential magazine Dyn, which was founded in Mexico City by the painter and philosopher Wolfgang Paalen, a former colleague of Breton’s whose inaugural editorial “Farewell au surréalisme” did much to set the magazine’s tone, Motherwell described his less individualistic alternative. Building on primitivist, anthropological interests that had been established in earlier issues of the magazine, most notably in the fraught “Amerindian Issue” published in 1941, Motherwell worked to shift the movement’s emphasis from mind to matter. In his 1942 essay “The Painter’s World,” he explained that “Painting is a medium in which the mind can actualize itself.” “The medium of painting is color and space,” he continued; painting is “the mind realizing itself in color and space.” As Robert Hobbs has argued, Motherwell’s description of painting as a “medium of thought” marked a fundamental transition within Abstract Expressionism, pushing the movement away from the psychic automatism that Pollock had retained, albeit in an altered form, from Surrealism, to what Motherwell elsewhere referred to as “plastic automatism.” Unlike psychic automatism, plastic automatism did not pretend to offer direct access to the unconscious, whether personal or collective. Instead, it limited itself to indirect access, filtering thought through an impersonal medium.

The process of depersonalization that the Abstract Expressionists had gotten underway in the 1940s and 1950s accelerated in the 1960s. After the enthusiasm for what remained of the more idiosyncratic elements of Surrealism peaked and waned, and as interest in the gestural paintings of Pollock gave way to a new enthusiasm for the more restrained color field paintings of Barnett Newman and Kenneth Noland, a new generation of painters began exploring Surrealism’s late echoes. That led to what Scott Rothkopf has called “a qualified reemergence of surrealism.” By 1966 Artforum had published a special issue dedicated to Surrealism that featured on its cover a work by Ed Ruscha titled “Surrealism, Soaped and Scrubbed.” This would be the same time that Paul Thek was making elusive and impenetrable cast-from-life sculptures, which he would later describe as dealing in a sort of “social surrealism.”

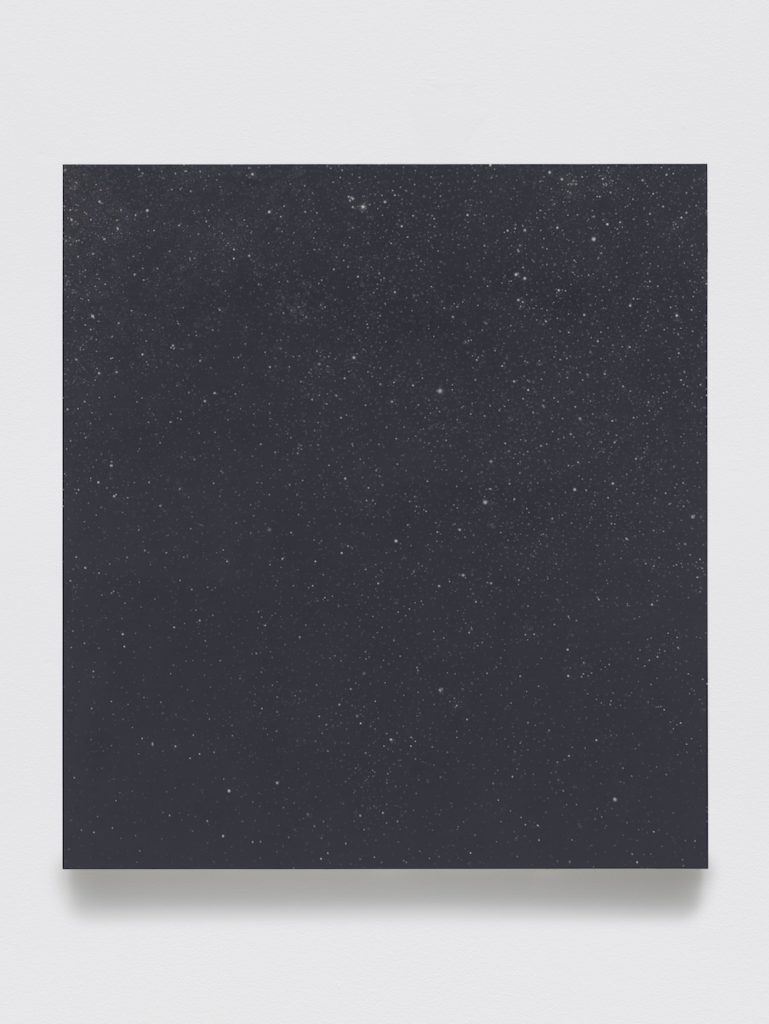

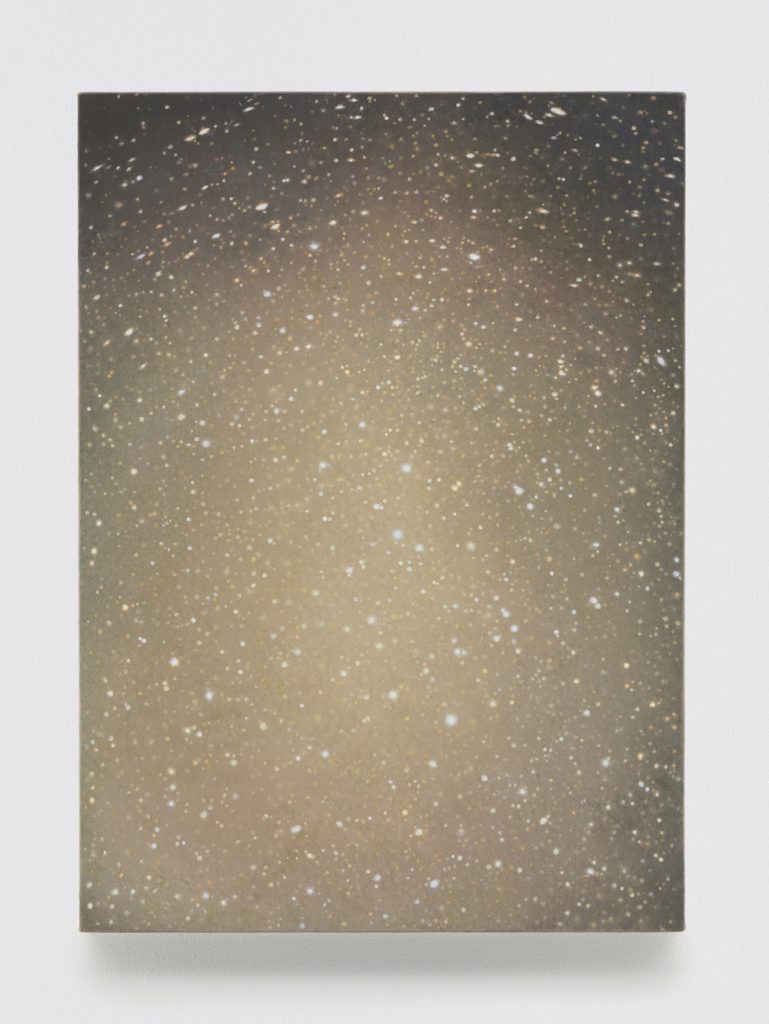

Announcing a functional link to Surrealism, these works led to a still subtler series of graphite drawings based on newspaper clippings, opened envelopes, and photographs. Based on “found objects” of a distinctly postwar sort, these later works continued the process of depersonalization described above, providing Celmins with subject matter that was, as she later explained, “outside” herself. Although these works were impersonal, they were also, needless to say, not without feeling. On the contrary, Celmins’s turn to found rather than invented images was, like Motherwell’s cultural turn some 20 years earlier, simply meant to distribute feeling through something sturdier. Moreover, as for Motherwell, so for Celmins that something sturdier was the artistic medium broadly conceived. As she has explained in numerous interviews, her works are meant to provoke what she describes as a two-staged process of seeing, first pulling the viewer in with the “emotion” that their subject matter evokes, and then pushing them out with the “rigor” that their painstaking method of making displays. Celmins discusses this two-staged seeing in terms of “layers.” “Layers create distance, and distance creates the opportunity to view the work more slowly and to explore your relationship to it,” she explained in a 1992 conversation with Sheena Wagstaff. A few years later, in an interview with Jeanne Silverthorne, Celmins again broached the subject of layers. Describing how one particular night sky work was made up of layer upon layer of paint conscientiously applied over many months, merging the limitless depth of its subject with the sheerness of its surface, she asked her interviewer, “Do you sense the layers?”

At Matthew Marks, you do indeed sense the layers. In Two Stones (1977/2014-2016), a work that continues a series that Celmins started in the mid-70’s, they come gradually into view. Two stones, one found one made, serves as something of a test case for how to approach Celmins’s practice. After an initial moment of similarity it is the difference between the two components that captivates. What had seemed to be the indifferent speckling of pink and grey mineral deposits are, after a time, revealed to be feathered strokes of paint laid patiently over bronze — a knowing layer of culture in place of an unknowing bit of nature.

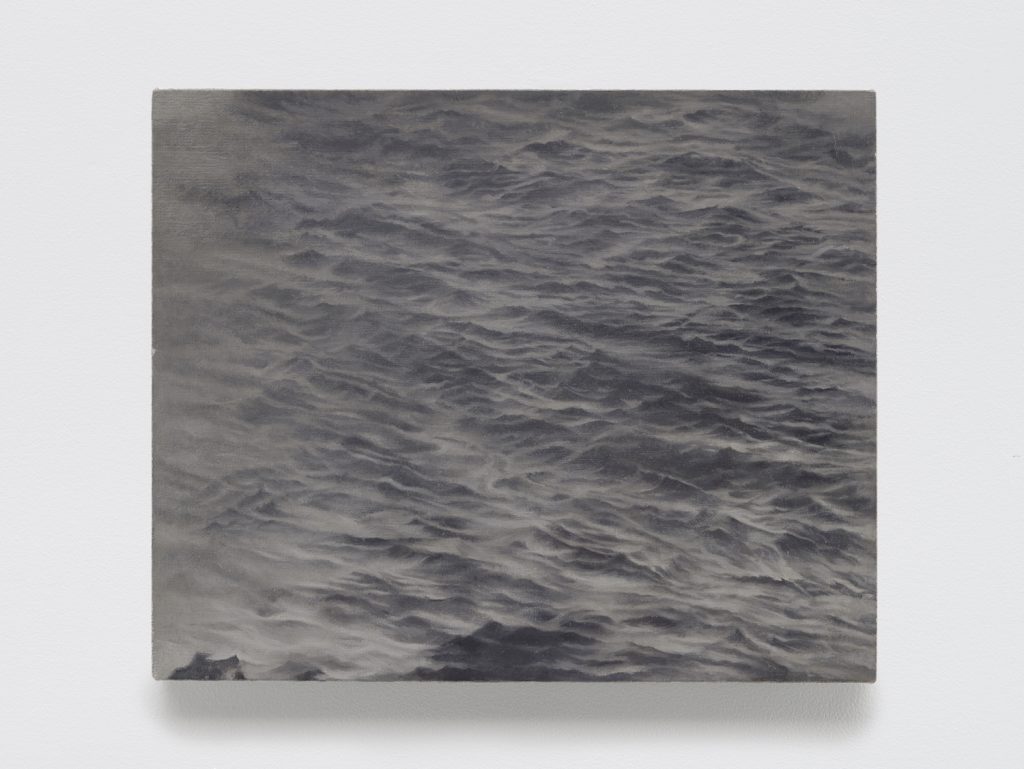

At this point, the layers begin to gather and you realize that what you are seeing is not simply six paintings of one photograph after all. Rather, what you are seeing is six paintings of the photographic medium. That becomes clear when you begin moving back again, appreciating, beneath the shifting values of white, black, and grey, the range of unintended but still-resonant registers that photography can itself convey.

The layers continue to gather when you discover that, in addition to being made up of paintings of the medium of photography, the series is also — at the risk of being pedantic — made up of paintings of a single painting of the medium of photography. The earliest component of the series, the one farthest right in the installation shot included here, was made by Celmins in the mid-1980s and sold to an early collector at the close of the decade. Upon that collector’s death, the painting was returned to Celmins, having been left to her in the collector’s will. A “found object” twice removed, the painting served as the starting point for the rest of the series, a fact that, once realized, interposes still more distance between the viewer and the work’s ostensible subject — distance that is filled by the work’s real subject: the acute and demanding attention that is involved in Celmins’s way of working.

In other words, instead of reaching back into the unconscious, as was the case in Breton, affective pressure pushes out sideways as social customs, habits, and norms — the whole impersonal substrate that mediates our personal lives — become available for aesthetic reflection. As though she were considering the kind of elsewheres that had so transfixed earlier avant-gardes only to then forego them for being flimsier than advertised, Celmins reveals the promised depth of the pictured seas and skies to be there for the taking in our everyday reality — assuming that reality is one that we, by mimicking Celmins’s careful attention, have, in her words, “doubled.”

In that same 1995 interview where Celmins asked whether Jeanne Silverthorne could sense the layers, she also gave some indication of what she thought that sensing might accomplish. “My intention is to make a fat, full form,” she explained. “Between the tangible, flat canvas and the volume of all those things like memory, and actual three-dimensional space, and how we experience the world, is where the chance to build the form comes. It looks like a narrow space from outside, but once you get in there and start to work it gets bigger. And I expect a lot from that space.” It is safe to say that when Celmins’s first full-scale retrospective in over two decades opens next year at SFMoMA before heading east to the Breuer, those expectations will be met.