“55 Voices for Democracy” is inspired by the 55 BBC radio addresses Thomas Mann delivered from his home in California to thousands of listeners in Germany, Switzerland, Sweden, and the occupied Netherlands and Czechoslovakia between October 1940 and November 1945. In his monthly addresses Mann spoke out strongly against fascism, becoming the most significant German defender of democracy in exile. Building on that legacy, “55 Voices” brings together internationally esteemed intellectuals, scientists, and artists to present ideas for the renewal of democracy in our own troubled times. The series is presented by the Thomas Mann House in partnership with the Los Angeles Review of Books, Süddeutsche Zeitung, and Deutschlandfunk.

The video of Karen Tongson’s speech can be viewed below.

¤

I consider it a great honor to speak to you in the spirit of Thomas Mann’s “Deutsche Hörer” addresses delivered throughout the course of World War II, during which he implored his people from a place of exile, to reject the regime they capitulated to in a moment of spiritual weakness: the kind of weakness preyed upon by reactionary nationalists. By fascists. In July 1942, Mann asked his fellow Germans, “When will you finally throw out the infernal good-for-nothing who does all this to you and who has made the German face look like a Gorgon’s grimace? When will you give it up and capitulate before reason?”

We are less than one month away from the 2020 presidential election here in the United States. Democracy itself is on the line, and it would be remiss of me not to echo Mann’s sentiments in an appeal to the American public. I am, however, somewhat less optimistic than he was when he declared in that same address that “the end of [Nazism] is approaching… it will come soon… An end will be put to its trashy and disgraceful philosophy, and all the acts of trash and disgrace which have sprung from it.”

I needn’t recapitulate all the 45th President of the United States’ many “acts of trash and disgrace” in my remarks. To do so would consume the entire length of this address, as well as the other 54 scheduled alongside it. But I must acknowledge where we are at this moment, even though the horrors I’m about to catalogue in the broadest of brushstrokes today will surely have worsened, even in the time between the taping of this address, and when you first hear it.

Over 7 million Americans have been infected, and over 200,000 have already died from the COVID-19 pandemic as a result of the Trump regime’s malfeasance and admitted deception. In my beautiful home state of California, wildfires continue to rage, destroying life and land amidst all the other ravages wrought by our climate apocalypse. Even as civil uprisings continue against this nation’s systemic racism, and in memory of our Black and brown brothers and sisters slain by the police, radical right wing and white supremacist groups are being granted increasing legitimacy by the administration and its organs of propaganda. An authoritarian crackdown continues against the free press, who have been openly fired upon, roughed up, and arrested by a militarized police force. And anyone who declares themselves against fascism is also being brutalized by these same forces, as well as some more sinister, with Antifa emerging as the contemporary equivalent of “the communist” who was used as a bogeyman and scapegoat during the rise of the Third Reich.

The fact that I could go on ad nauseum is a tragedy in and of itself. I won’t mince words: democracy is on the brink here in the United States. It bears reminding, however, that the representative democracy that we are now left to defend has always been compromised, and mediated by elites with both the capital and power to ensconce themselves as our representatives. Indeed, our representative democracy’s attachment to the ruling class has enabled the exploitation and erosion of its own systems in order to keep the privileged in power.

Like everyone who isn’t one of the indigenous inhabitants of this land, I am an immigrant to the United States. And like Mann, who lived in Los Angeles in exile from an authoritarian regime, I too first moved to the Southern California region from a nation under the thumb of an authoritarian dictator, Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines. I was born in 1973, a year after Marcos declared martial law. All the stories my family tells about the night of my birth feature clever embellishments on how each of them maneuvered their way around curfews and armed battalions to get to my mother and me in the hospital.

It is little wonder that as a kid, I dreamed of what “democracy” could mean beyond the shadow gestures of the democratic process rehearsed by the regime I grew up with in Manila. It’s why, as a young teen, I fetishized the concept of American democracy and “the vote,” despite the fact that I bore witness to my grandmother and my other relatives enacting the futile ritual of casting ballots “just in case,” only to be met with the same result over and over: another landslide victory for Ferdie and his cronies.

Now this is usually the part of the story primed for an uplifting plot twist, where one talks about “coming to America,” and growing up to exercise one’s franchise but a few short years after shedding tears at the televised spectacle of the 1986 “People’s Power” revolution in my home country. This is when I stare directly into the camera with a look of solemnity and implore you to vote. I do want you to vote. But unfortunately, “achieving democracy” never truly signals the end of the struggle, only the beginning.

Where did Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos flee, albeit several thousand shoes lighter, but to the good old US of A. Here Ferdie got to live out the rest of his years in the tropical leisure of Hawai’i, another territory which, like the Philippines, was “annexed” by the United States in 1898. The Philippines’ deposed well-coifed despots were rewarded for playing nice with American presidents from Nixon to Reagan; for capitulating to the US’s strategic military interests in Southeast Asia in exchange for permission to pillage their own country of all its resources and promise.

I learned even after that — once Corazon Aquino assumed power and little changed for the poorest of the Filipino people, as well as in the wake of multiple coup attempts, and a presidential impeachment leading up to the “free” election of another would-be strongman who remains in power today, Rodrigo Duterte — that democracy cannot simply be reduced to a change in leadership or representation. “Freedom” in name means nothing without the redistribution of power, resources and care to the most disenfranchised. Democracy means nothing without a genuine reckoning with the legacies of colonialism, genocide, enslavement, and the everyday business of disenfranchisement we have become attenuated to through the capitalism that we confuse with “freedom” itself.

It grieves me to experience such a feeling of uncanniness in this moment of American history, to experience the banality with which we increasingly accommodate evil every day. As Indi Samarajiva wrote in a recent op-ed, “If you’re waiting for a moment where you’re like ‘this is it,’ I’m telling you, it never comes. Nobody comes on TV and says ‘things are officially bad.’ There’s no launch party for decay. It’s just a pileup of outrages and atrocities in between friendships and weddings and perhaps an unusual amount of alcohol.” Though his sentences are dripping with satire, Samarajiva’s point is deadly serious.

We who are privileged enough to not yet be immediately imperiled, have already absorbed kids in cages, the sterilization of immigrant women, COVID-19 casualties in the realm of a “ 9/11 attack every day for 67 days” and climbing. The daily news parries with the notion that the President might not step down from office, while we prepare for the kind of election chaos that usually warrants international monitoring. Many of you already know all of this, so what’s the point of me reiterating the horrors of our current conditions if simply knowing hasn’t been enough to change anything?

Just as evil and terror have instrumentalized the banal, and have found bureaucratic pathways to enact harm — why else do you think the US Postal Service has found itself at the center of such controversy in these dark times? — so too might we be able to forge acts of resistance and repair through the everyday; through the tasks and tools we have at our disposal. In a recent piece making the rounds from Waging Nonviolence, the author and activist Daniel Hunter tells us the “10 things you need to know to stop a coup.” (I truly miss the days when viral listicles were about the 5 best ugly-cry episodes of Friday Night Lights, or the top 10 candies beloved by GenX). In his piece, Hunter underscores the critical interventions made by everyday people, whose refusal to do everyday things, like printing and distributing propaganda, once made all the difference.

He tells the story, for example of a coup leader in 1920s Germany who was “wandering up and down the corridors looking in vain for a secretary to type up his proclamations.” How can we be that secretary? How can we refuse business as usual to ensure all our ballots are counted? How can we be like nurse Dawn Wooten, the whistleblower who revealed the medical atrocities being performed at ICE detention facilities? Or like the US Postal Service workers resisting Postmaster DeJoy’s sabotage of their own agency, and his dismantling of their essential services?

We are so used to the drama and flourish of resistance, that we forget how even the smallest refusals — refusing to do as we’re told, refusing to follow orders — bear the potential to save our neighbors, and to save the world. As adrienne maree brown writes in her important book, Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds: “I think it is healing behavior, to look at something so broken and see the possibility and wholeness in it.” Our broken Democracy is calling upon us to see the possibility and wholeness in it. Now is our time. This is our moment.

As my dear, departed friend, the queer of color theorist, José Esteban Muñoz wrote in his most recent book The Sense of Brown (which was released posthumously just a month ago): we must “amplify and transmit [the] recitation of dreams and contribute to a project of setting up counterpublics — communities and relational chains of resistance that contest the dominant public sphere” (2020, 64). It is within our power, a power we mistakenly perceive as limited, to refuse, resist and withhold until atrocity has no pathways to fruition. It is in our capacity to make manifest the chains of affiliation and resistance required to keep the remaining vestiges of this representative democracy intact until we dream something better into being.

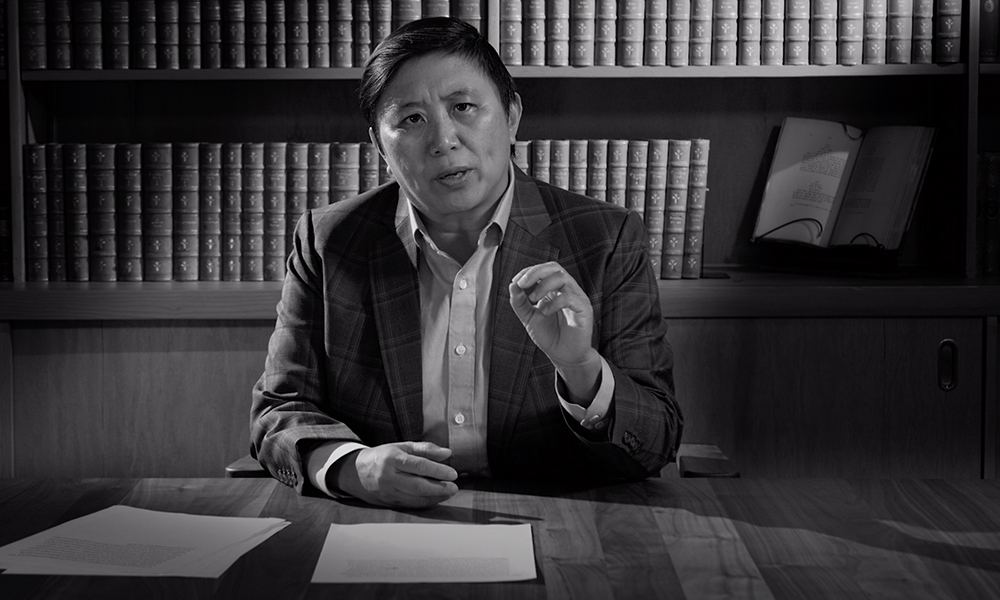

Photo credit: Thomas Mann House / Boris Schaarschmidt.