All Photos by Jeffrey Wasserstrom

I’ve just returned from a trip to China that began with a week in Shanghai, where I participated in one literary festival, and ended with a few days in Beijing, where I had a small role in another bookish event of the same kind. It was good to go back to those cities, which I’ve visited regularly since the mid-1980s, especially since temperatures were higher and smog levels lower than I’d feared they might be, and the panels at Shanghai’s M on the Bund and Beijing’s Capital M went as well as I’d hoped they would. But as satisfying as returning to each metropolis was, I was particularly glad to be able to slip in a side trip to Qufu, a small city in Shandong Province, best known for its ties to Confucius, that I’d never been to before. This visit has changed forever the way I think about the historical treatment of the ancient sage and how I think about a canonical modern Chinese text, Mao’s Little Red Book.

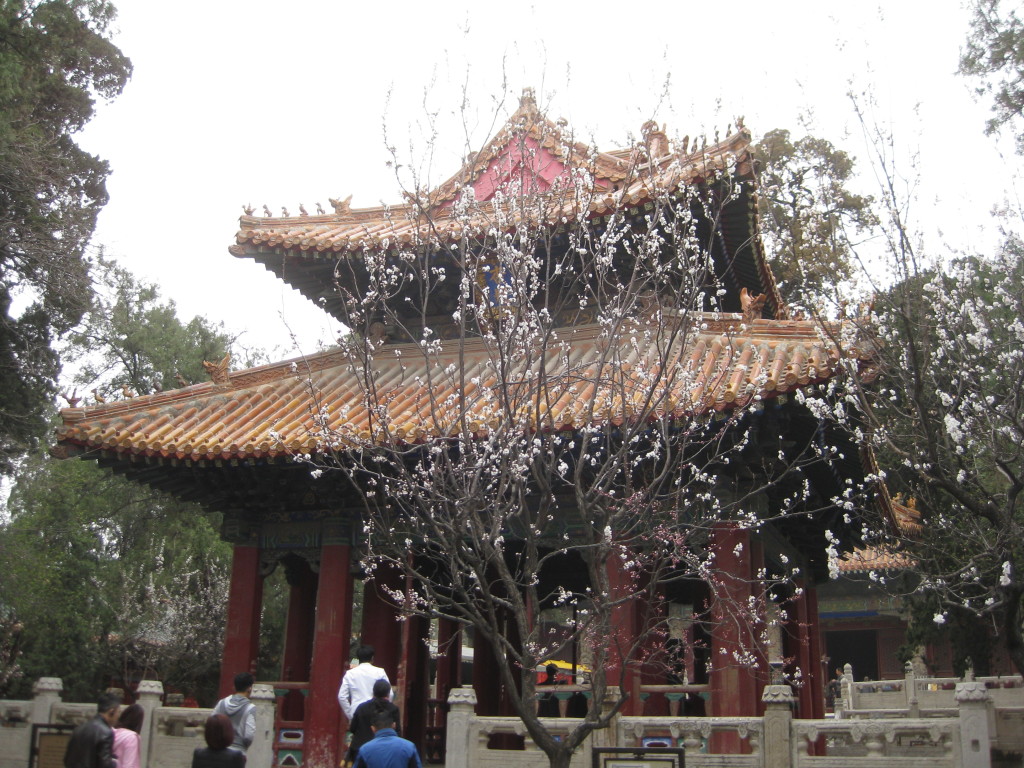

I decided to go to Qufu, which is still home to many members of the Kong lineage of which Confucius was part, as soon as I realized how simple it would be to fold this place I’d long been curious to see into a rushed itinerary. Thanks to the opening of a new bullet train route, I could set off from Shanghai in the morning, get to Confucius’s hometown after being whisked along the rails for three hours, spend the afternoon seeing the main local sights (the Confucius Temple, the Confucius Mansion, and the massive Kong family cemetery that includes the philosopher’s tomb), and then continue on by rail to Beijing the same evening, getting to the capital two hours later.

Qufu had been high on my “to see” list for years due to my interest in the dramatic about-face the Chinese Communist Party has made regarding Confucius. He is now treated as a kind of national saint but, to borrow from sports writing parlance, his posthumous career has had the ups and downs of a classic comeback kid. Most significantly, as Maura Cunningham and I note near the beginning of our China in the 21st Century: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford University Press, second edition, 2013), as recently as the 1970s he was “excoriated in a mass campaign that presented him as a man whose hide-bound, anti-egalitarian ideas had done great harm to many generations of Chinese men and even more damage to generations of Chinese women.” How, I wondered on the train to Qufu, would sites associated with Confucius deal with the various reversals of fortune that have been experienced by the sage, who was out of favor among intellectuals in the 1910s, only to be exalted by Chiang Kai-shek in the 1930s, before being reviled throughout the Mao years (1949-1976) and then surging back into official favor under the Chairman’s successors? In symbolic terms, might Qufu be that most unusual sort of contemporary Chinese locale — a completely Mao-free zone?

My first fifteen minutes in Qufu were frustrating ones. They were spent circling the train station with a friend, who was also shuttling between the Shanghai and Beijing literary festivals and had agreed to join me in some Confucius-themed sightseeing, trying to figure out a way to leave our bags in a safe place while venturing into the city. My initial impression, captured in a couple of photographs I took during breaks from our quest to find lockers or a secure luggage room (the closest we got was a waitress pointing to a closet in her restaurant that she thought might be a good place to stow our bags), was of a city that was all about Confucius and had no room for Mao, and was unconcerned with the ups and downs of the former’s career. Bigger than life in the station’s main hall was a statue of Confucius that gazed down on all visitors and was described simply as a revered figure from ancient times. And when I stepped outside, I saw the same visage gazing down at me benevolently from a giant poster that placed Confucius between a needle-nosed bullet train (suggesting that Qufu is a place that honors venerable traditions but is part of a modern country) and a hillside (nodding to the city’s only claim to fame unrelated to the Kong family, which is its proximity to Mount Tai, a leading attraction for Chinese lovers of nature).

Mao came into the picture, though, as soon as we gave up on leaving our bags at the station and decided to hire a taxi with a decent-sized locked trunk for the whole afternoon. Hanging from the cab driver’s rearview mirror was the same good luck medallion emblazoned with the late Chairman’s face that one sees in taxis across China. As he drove us to our first stop, the Confucius Temple, he pointed to rows of buildings going up along the highway and cranes in the distance that were part of still grander development plans. Qufu, the voluble man insisted, was destined to become a major tourist site and a bigger city, since travelers from Korea, Japan and Taiwan as well as from all parts of China would want to come and pay homage to Confucius. Was he sure, I asked, that the population and local tourist trade would grow enough to justify all the building underway? Definitely, he said, nodding his head vigorously, and then offered two pieces of evidence to back up his confidence. First, the Shangri-La luxury chain had recently opened a hotel in Qufu. Second, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s wife, Peng Liyuan, had close ties to the area, so money was bound to flow into the region.

Responding to my other questions, he said that he wasn’t part of the Kong lineage, to which an estimated 20% of the just over half-a-million people living in the greater Qufu are said to belong, but he was a local. And as such, he was very proud to be from the same place as a great sage and hero of Chinese history.

I asked if he saw anything strange about saying that while having an image of Mao in his car, since the Chairman, an iconoclast from an early age, had despised Confucius throughout his adult life. The driver just bellowed with laughter. I asked if he even knew about the anti-Confucius stance of Mao’s day, and he nodded and, still laughing, shouted out “Pi Lin, Pi Kong!” This is the shorthand for the most famous anti-Confucius campaign of all, which took place in the early 1970s. Making use of the term “pi” for criticize, it targeted both the ancient philosopher (“Pi Kong”) and Mao’s erstwhile heir apparent, Lin Biao (“Pi Lin”). Lin, a People’s Liberation Army leader, had been seen as a devoted follower of Mao and staunch defender of Mao’s interpretation of Marxism and iconoclastic critical stance toward Confucian ideas. When the tide turned against Lin, though, he was accused of having been a secret supporter of all things reactionary, including Confucianism, which provided the tortured logic for a double-barreled “Anti-Confucius, Anti-Lin Biao Campaign,” which threw alleged ancient and contemporary enemies of the revolutionary cause into the same vile category.

When we made our way through the city’s three major sites, the main focus of the texts aimed at tourists, from booklets to plaques, was simply the glories of Confucius and the rich legacy of the lineage to which he belonged and the imperial era he is often used to represent. There was not any mention, at least in any text I saw, of the fact that Confucius had only been revered during part of the People’s Republic’s history.

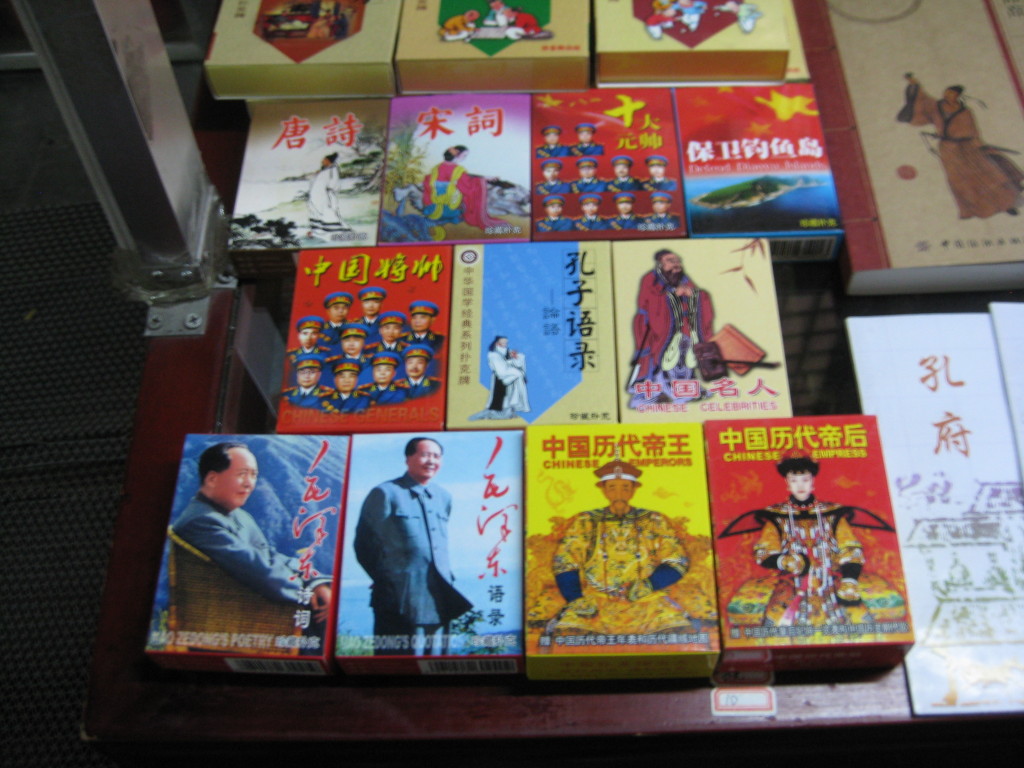

Every now and then, though, the recent past would come into view, since both some official gift shops and many of the unofficial booths selling trinkets near to the key sites contained objects associated with Mao and his era in powers. Inside the Confucius Mansion, for example, there was a shop selling various decks of cards: some featuring Confucius, others celebrating emperors, and still others honoring Mao. Meanwhile, between the Temple and the Mansion, there were different but equally promiscuous displays of statues, with Confucius, the Buddha, and Mao all jumbled together.

Of all the curious juxtapositions of objects, though, there’s one that stands out most to me as I look back on my Qufu afternoon, which I spotted at a souvenir stall displaying, among other things, a lot of small books with red covers. A set of four red booklets in particular caught my eye. Two were differently packaged versions of the classic Little Red Books containing Mao’s selected sayings; but the other two were similarly designed and titled copy-cat texts, made up, in this case, of quotations by Confucius.

The side-by-side placement of Little Red Books associated with Mao and Confucius seemed curious for so many reasons that it is hard to know where to begin in attempting to unravel or even describe them. To try to sort them out, I spent some time on the plane ride home perusing an advance copy of Mao’s Little Red Book: A Global History, a wonderful anthology edited by Alexander Cook that Cambridge University Press is publishing next month. The chapters in the volume, by talented scholars based in different countries and different disciplines, explore everything from the way the eponymous text was created and distributed within China to the meanings it took on when it made its way to foreign countries such as India, Italy, Albania and Peru.

Here are two things the chapters by Cook and his collaborators suggest might be worth considering while pondering the apparent contradiction of different sorts of little red books placed beside one another on that table in Qufu. Lin Biao, before being castigated as a closet Confucian, took a special role in promoting Mao’s Little Red Book and wrote a preface to the best-known edition of it. And while the titles and even design features of the newly created Little Red Books of Confucian sayings imitate features of Mao-era creations (note the round images of the authors on some books), the original Little Red Books of quotes by Mao were themselves inspired in part by pamphlets and booklets from earlier times that brought together aphorisms from the Analects and other classical Chinese philosophical texts.

I thought that Qufu would be the sort of place I’d only want to visit once, but the more I ponder what I’ve come to think of as my Little Red Books photo, the more certain I am that I’ll need to go back there again. I will want to see if the cab driver’s prediction of great things for the city comes true. I may even see what it’s like to stay in a Shangri-La in Confucius’s hometown. And I will definitely do something I foolishly forgot to do on my first visit: buy one of the copy-cat Little Red Books that has a picture on its cover of, and words inside by, a philosopher Mao thought of as having ideas that were the polar opposite of his own.

* To learn more about some of the topics brought up in this post, see the following three works:

1) Shades of Mao: The Posthumous Culture of the Great Leader. Page 33 of this pathbreaking work edited by Geremie R. Barmé contains a discussion of a Confucian “Little Red Book” published in Qufu in the early 1980s; page 86 has a photograph of one.

2) A Continuous Revolution–Making Sense of Cultural Revolution Culture. This book by Barbara Mittler, which recently won the American Historical Association’s Fairbank Prize, has discusses connections between Confucian and Maoist texts and practices and has a good treatment of the Anti-Confucius, Anti-Lin Biao Campaign; see especially page 193.

3) “To Protect and Preserve: Resisting the Destroy the Four Olds Campaign, 1966-1967.” This chapter by Dahpon David Ho in The Chinese Cultural Revolution as History (a volume edited by Joseph W. Esherick, Paul G. Pickowicz, and Andrew G. Walder) contains a fascinating and detailed account of Mao era activities in Qufu, including pitched battles between those trying to deface and those fighting to defend the Kong family cemetery.