I saw Wild Nights with Emily alone on a Sunday night — a kind of ritual in my life for that night of the week. I head to the movies right around the time I start to get nervous, at 5:30 or 6, about dying, never being loved, impending doom, and so on. Movie outings get me out of that funk, and sometimes takes me above and beyond. This one certainly did. I wrote in an email to a friend after I saw it: “i am so moved by History ha ha. i guess more so i’m moved by disruptions of history; i guess more so im moved by truth and lesbians.”

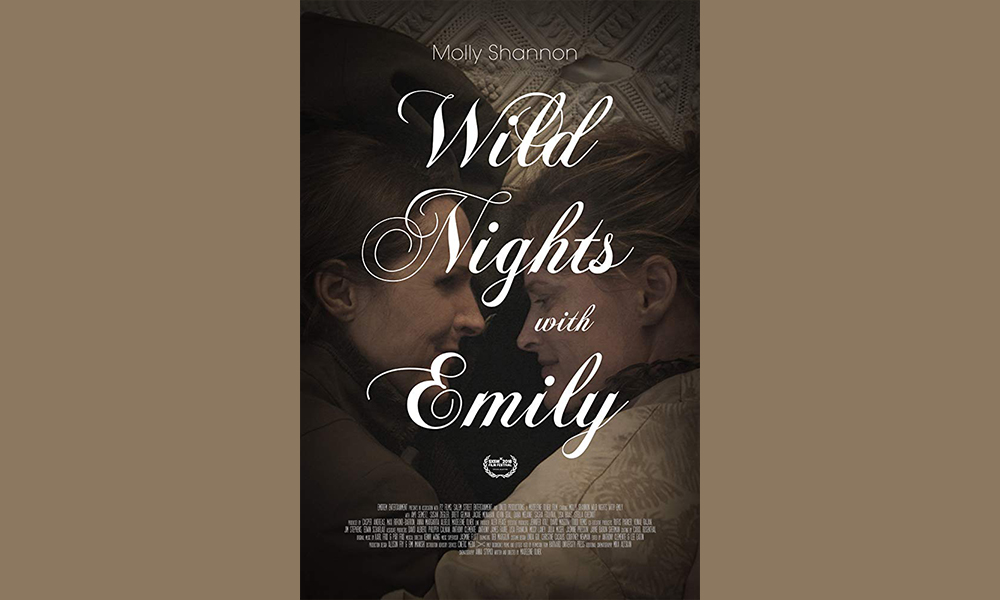

The central themes of Madeleine Olnek’s newest film are just that: disruptions and truth and lesbians. It is a retelling of the life and career of Emily Dickinson (played by Molly Shannon) focusing on her life-long relationship with her sister in-law, lover, and muse, Susan Dickinson (Susan Ziegler). Olnek pulls back the curtain to reveal the mechanics and conventions of history at work, bringing to the surface details of Dickinson’s biography that have been often, probably deliberately, omitted.

As the film tells, Susan Dickinson capitalized on the union of matrimony by marrying Emily’s brother so that the two could live next to each other and no one would be suspicious of their close friendship and rather, charmed by their sisterly affection. The cinematic depiction of the relationship between the two women is based upon a collection of letters and poems Emily sent to Susan over her lifetime. The film was extensively researched, using the Dickinson archives at Harvard and Amherst that house her library and papers.

The film is laced with wit and dark humor. It debunks old wives’ tales about Dickinson while entertaining the small possibility of their truth. Who we thought we knew as a reclusive spinster working from divine genius we come to know as a lesbian intellectual. Of her choice for the leading role, Olnek says, “I felt if Molly Shannon played Emily Dickinson people would finally understand who she was.” And Olnek’s choice worked to great effect. Shannon’s appeal and familiarity successfully advance this “new” version of Dickinson as a likeable, nuanced figure.

Mabel Todd (Amy Seimetz), an eager and self-absorbed young woman, based on a real figure, becomes the publisher of her work and the producer of her “brand” after Dickinson’s death. Todd “discovers” her poems, swiftly spinning a narrative in which Emily is a modest and depressed woman who never wanted her poems published, rather than a working lesbian poet who was subjected to misogynistic prejudice by those with the power to publish her work.

Olnek gets at the dark absurdity of misogyny: how bizarre, how preposterous it is, but simultaneously, the ludicrousness of posthumous idolatry. In her depiction of Mabel Todd, whose intentions may seem benign, Olnek exposes her to be destructive and driven by self-interest. The film critiques a contemporary trend in the art and film world: the exhuming of careers, the cleansing of histories, and the simplification of narratives in which She is always the underdog who becomes the hero.

When a publisher, Higginson, condescendingly poses the question “What is Poetry?” Emily promptly replies with a list of the things that are poetry, including something along the lines of: “When the top of my head gets cut off and everything pours out, I know that is poetry.” A comedic yet poignant moment, in which Higginson’s ignorance is revealed and Dickinson asserts her wit. The question is only rhetorical because he does not in fact have any ideas about what poetry could be. But Emily does. He leaves their meeting, rejecting her request to be published in his paper.

This film also challenges the tired and lazy “powder-puff” reboot trend in which previously male-centric blockbusters are “reimagined” (with little to no imagination, mind you) starring all-female casts, brazenly exploiting contemporary concerns with representation and identity politics. The motto being: Slap a pair of tits on Captain Marvel and you’ve got a feminist hit! Wild Nights refuses to indulge in that kind of pathetic navel-gazing remake and does just what those films fail to do: wrestle with the ambiguous histories of women and queer people and explore the malleability that that ambiguity affords.

As I see it, Wild Nights introduces a new genre — a kind of mock period piece biopic with a lesbian feminist bent. The film pokes fun at the often bland or unimaginative attempts to represent an era with historic authenticity: the wigs and costumes and strict adherence to antiquated language. In the style of Miloš Forman’s Amadeus and Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette, both films that incorporate contemporary colloquialisms and aesthetics, Wild Nights expands the possibilities of the historic biopic. The art direction features obviously hokey props (plastic flowers, fake cats) and cheap looking costumes and set pieces, almost breaking the fourth wall, reminding the audience of the dramatic conventions that these films often follow. With this playfulness, the film critiques the obsession to (re)construct biographies of cultural icons, to make their lives out to be more significant than their work. The film observes our compulsion to sensationalize — to ascribe our icons our own desires and to simplify them in order to understand and explain the existence of their work. Of course, while these reconstructed biographies might entertain us, they ultimately detract from the truth, performing a kind of erasure. In the striking final sequence, the screen is split in two: one shot shows Susan tenderly washing Emily’s corpse; the other, Mabel erasing Susan’s name from Emily’s poems and letters. Olnek revels in the irony, the discrepancy between what we want to believe happened and what probably really happened.

When the movie let out I went to the bookstore next door in search of the book of letters between Emily and Susan. I wasn’t in the mood to look very hard, so instead I bought a copy of Not Me by Eileen Myles, the first book of theirs I encountered in college. To me Myles is essentially a cultural descendant of Dickinson, another Yankee lesbian poet, and the first I fell in love with.

I hopped

on an Amtrak to New

York in the early

‘70s and I guess

you could say

my hidden years

began. I thought

Well I’ll be a poet.

What could be more

foolish and obscure.

I became a lesbian.

Every woman in my

family looks like

a dyke but it’s really

stepping off the flag

when you become one.

While holding this ignominious

pose I have seen and

I have learned and

I am beginning to think

there is no escaping

history…

(An American Poem)

I didn’t have a copy of my own. I had always used my ex-girlfriend’s, which made the purchase just as appropriate as the Dickinson letters, I thought. I probably shouldn’t have bought anything that night, spared my checking account the hit. But it was 5:30 and I needed poetry. I needed to be taken out of my own thoughts, to indulge the possibilities of an alternative history: that our beautiful, melancholic poet-ess laureate was just a cranky dyke.