A few weeks ago I found myself in Bangladesh for the Hay Festival. I was visiting the capital Dhaka at the invitation of our friends at Bengal Lights, a literary journal and book publisher affiliated with the University of Liberal Arts, Bangladesh. In the typical Western imagination, a literary festival is not what crops up first at the mention of Bangladesh. Instead you get, if anything, a Third World potboiler of cyclone disaster, garment industry horror, and political unrest, backed by a George Harrison soundtrack (if you’re old enough to remember).

But get this: Bangladesh, the People‘s Republic of Bangladesh, is a nation of Muslims with a secular constitution. It provides more U.N. peacekeeping forces than any other nation in the world. And since the Liberation War with Pakistan in 1971 (the same year Ravi Shankar got his buddy George to write a song about it) Bangladesh has made great strides in primary education, gender equity, population reduction and health services.

The capital Dhaka is also home to one of the many Hay Festivals that have proliferated around the world. Now in its third year, I arrived at the Hay with a contingent of Americans, including Mario Bellatin, the Mexican novelist, David Shook, poet and translator, and Eliot Weinberger, the essayist and renowned Octavio Paz translator. Dhaka, a megacity, teems. With a population of 15 million, it is perhaps the densest city in the world. It surprised us at every turn.

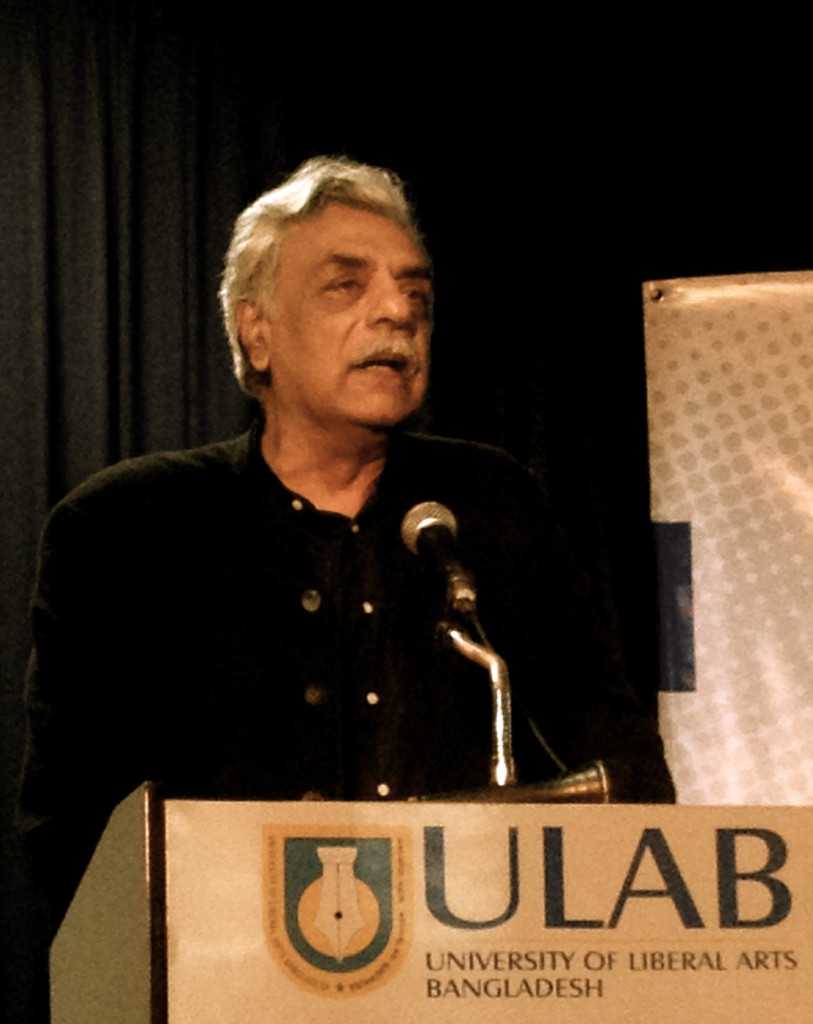

Tariq Ali, the British Pakistani journalist and novelist headlining this year’s Hay Festival in Dhaka, had not been been back to Bangladesh since before the ’71 Liberation war. At that time, he predicted that anything short of independence for what was then East Pakistan would not be enough. His return was, to say the least, well received. He appeared several times on panels and speaking engagements and each time the Q&As had to be cut short due to time constraints. His rather grim assessments of global capitalism’s destructive path – Ali’s unrelenting focus – were incapable of dampening the enthusiasm of the Hay attendees. But this iconic figure was not the only one to enjoy such a reception. Other panels were equally enthusiastic, whether the topic was translation or Latin American fiction or “world literature” – Tariq Ali or no Tariq Ali – Dhaka’s literary and intellectual scene is engaged, opinionated and focused on a global discourse. It was inspiring to witness such involvement given what so often feels like a parochial and self conscious community back home. Even the headliner Ali, who lives in London and clearly brought a very contemporary brand of First World pessimism, could not dampen the mood. In fact, his pessimism seemed, refreshingly, out of place.

In the street, the bicycle rickshaw prevails in Bangladesh though it’s virtually disappeared in other South Asian cities. Confiscated rickshaws get impounded by the police and sit, waiting to be recouped in lots outside the city. You can buy a new bicycle rickshaw for about $300, but a majority of the drivers rent their rickshaw for a few dollars a day. In trying to wrap your mind around Dhaka – an impossible task to be sure – it might be best to simply ride with the rickshaws.

The sheer awesome human effort of the drivers, collectively, might just power not just their own movement but the city’s daily electrical output as well. Even in nightmare traffic, even in the chaos of streets without apparent rules, some of the happiest faces I’ve seen in any urban setting are passengers on the bicycle rickshaw – mothers and children, friends, lovers – when they are suddenly breaking free onto an open stretch and sailing in the open air with a contentment you never see inside a New York City cab. Dhaka never lets you forget what a city is for.

Like other “emerging market” cities, Dhaka (and its economy) grew from a provincial capital to an unplanned megalopolis in less than forty years.

Dhaka’s architecture defies easy category, then – finished, unfinished, ruined – it’s not always immediately clear. But the primacy of rebar is without question – sprouting like weeds from concrete pillars and pilings on rooftops of apartments and office buildings wherever you look. At first, you think every building is perpetually under construction, or in the process of demolition.

A masterful dystopian effect, it has everything to do with lax construction practices though not what I first guessed was a kind of rainy day move: why finish a building when you might want to add on a story or two later? It should have been obvious there was no intention of adding to the weather-beaten urban-stained buildings, the kind which you mostly see in Dhaka. Instead, the city’s tax code – which collects only on completed buildings – compels the rebar rooftop style. It’s hard not to wonder at such monumental tax evasion. It’s also hard not to see that this endemic kind of corruption will be solved as the Bangladeshi middle class continues to grow and prosper.

And this is the thing about the Hay Festival Dhaka, and Bangladesh generally: though the political and social realities are still very difficult, there is ambition, and energy, and debate. Returning from Dhaka, back to our own problems in this country, I was reminded that the future is still a possibility.

Thank you, Dhaka.