This essay is adapted from a talk given at the Literature Translation Institute of Korea.

This year’s Pritzker Prize, informally known as the “Nobel Prize of architecture,” went to Isozaki Arata, one of the most celebrated architects in Japan. His more than 55-year-long career, the many and varied fruits of which include Los Angeles’ Museum of Contemporary Art, began at the University of Tokyo, from which he received his doctorate in architecture. In that program Isozaki had an exact contemporary by the name of Kim Swoo-geun (김수근), a Korean who had come to Japan after the outbreak of the Korean War to continue the architectural studies he had begun at Seoul National University. Though Kim wouldn’t make it to the kind of age at which one typically becomes a Pritzker laureate — much less to late in the ninth decade of life, when Isozaki received the prize — he would go on to become South Korea’s first modern architect.

Or at the very least, Kim would become the individual with the most convincing claim to have led South Korea’s very first generation of modern architects. In just over a quarter-century he designed more than 200 structures in his homeland and elsewhere: nation-building institutions, museums, housing, houses of worship, a vast and controversial electronics-market complex, a stadium, and even a subway station. The variety of purposes to which he built is equaled by the stylistic variety in which he built them: having emerged from his architectural education in the same kind of Europe-facing modernist mode in which so many of his Japanese colleagues began their careers, he then spent most of his career in search of a genuinely Korean architecture suited to the modern world.

Kim created his first notable design for submission to a competition, as many young architects do. It went unbuilt, as the first notable designs of many young architects also do, though Kim’s actually won the competition to which he submitted it. The contest was held in 1960 to select the design for a National Assembly building for the still-new Republic of Korea, and Kim came up with his while still based in Japan. Involving one low horizontal building and one tall vertical one in an arrangement that drew from the layout of Buddhist temples, his winning entry had yet to break ground by the time South Korean president Park Chung-hee took power in the coup of May 16, 1961, effectively hitting the still-new country’s political reset button.

“What is a National Assembly building?” said Kim about the thinking behind his design. “It is a hall of popular will. Popular will, to put it another way, is affection for the people. If the people see architecture that exudes affection, then they, too, will feel affection. At the same time, it has to have dignity. Dignified architecture makes for authority.” His words ajeong (애정), here translated as “affection,” and uieom (위엄 ), “dignity,” would go on to play a recurring role in his philosophy of architecture. And though such concepts may not come readily to mind when considering the eighteen-year presidential reign of Park Chung-hee — interested though he undoubtedly was in authority and its means of establishment — Kim nonetheless found favor under the strongman and his developmentalist regime.

Kim had returned to Korea in 1960, and not long after Park came to power took the job of designing the highly symbolic Freedom Center at the foot of Namsan, the mountain right in the middle of Seoul. Kim’s task demanded both a payment of ideological tribute and an visible declaration of intent to break from Korea’s uncritical importation of wholly Western architectural styles — a task he undertook in his early thirties, an age when most architects consider themselves lucky to be building detached houses. But to what extent the Freedom Center departs from the styles of the West remains debatable, especially given the debt its generous use of exposed concrete — a first in Korea — owes to the work of European modernists like Le Corbusier.

But Kim used that technique in service of not simply massive, imposing, angular forms, but massive, imposing, angular forms with curves here and there that make reference to the shape of traditional Korean roofs — and somewhat less plausibly, the form of traditional Korean padded socks. Though Koreans younger than the Freedom Center itself may no longer feel the building’s ideological resonance, this monument to Park Chung-hee’s brand of authoritarianism, militarism, and anti-communism has remained aesthetically appealing enough to stay in business in the 21st century as the J-Gran House wedding hall. Its amenities include a “Zexy Garden,” which, whatever it is, was surely unimaginable in Korea when the Freedom Center first opened in 1963.

That same year, Kim also designed an even more legibly symbolic building, this time in eastern Seoul: a bar atop Walker Hill, named for the American Army General Walton Walker, a leader in the Korean War who had died in Seoul thirteen years before. The shape of the Hilltop Bar also pays tribute to Walker, resembling as it does a giant concrete W — from certain angles, at least. Kim’s unusual structure still stands on Walker Hill, and still looks essentially the same, though subsequent renovation has downplayed all the concrete surface so architecturally fashionable in the 1960s, and the business occupying it has changed: the Hilltop Bar is gone, but Pizza Hill lives on.

In the mid-20th century, high-rises meant modernity, and so mid-20th century urban development, in the East no less than the West, meant high-rises. Yet despite Kim’s unofficial role as something of a state architect in a fast-developing state desperate to signal its own modernity, he seldom worked in that form. His Tower Hotel, first built to accommodate guests of the Freedom Center, is an exception: its seventeen stories, symbolizing the seventeen nations that took part in the Korean War, made it the tallest building in Korea at the time. It still stands out in its now startlingly unbuilt-on part of Seoul, though it does so no longer as the Tower Hotel but as the Seoul branch of Thailand’s Banyan Tree Club and Spa.

Kim’s work of the early 1960s would seem to impeccably demonstrate the sensibilities, both nationalist and pro-American, then demanded of any high-profile South Korean. But these credentials came into question in 1967, with the opening of his National Museum in Buyeo. Journalists, and even other architects, charged Kim’s design, reminiscent as it was of the Shinto Ise Grand Shrine, as excessively Japanese — a potentially career-ending accusation in those days, especially for a Korean not just educated in Japan but married to a Japanese woman. “Because traditional Korean architecture is my psychological foundation,” Kim insisted in response, “it is from traditional Korean architecture I have drawn influence.”

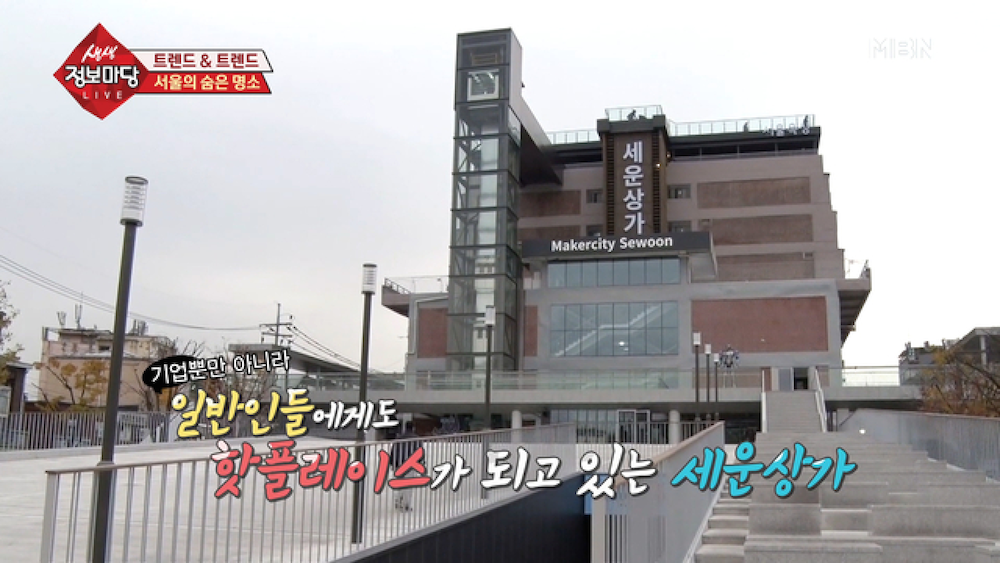

But years would pass before Kim could explicitly back this statement up a building. His projects then already under construction included Sewoon Sangga, a massive commercial and residential complex meant to cut through downtown Seoul like a convoy of concrete battleships. Built on a cleared strip of land that had been used as a fire break during the war and gave rise to a slum thereafter, Sewoon Sangga exemplified the development philosophy of then-Seoul mayor Kim Hyon-ok, nicknamed “the Bulldozer.” Initially conceptualized by Kim Swoo-geun as a “city within a city,” its ambitious design included expansive glass atria, a transportation system to connect all its buildings, and other features completely stripped away before construction due to budget constraints.

Kim ultimately disowned Sewoon Sangga because of these compromises, and Sewoon Sangga itself, after decades of infamy as a place to buy illegal adult materials and pirated media of all kinds, eventually fell into serious disrepair. It very nearly fell to the wrecking ball in the 2000s, and the demolition of its northernmost building was completed before the decision came through to preserve the rest. The refurbished Sewoon Sangga, now branded as “Makercity Sewoon,” has, in addition to the hundreds of legacy electronics shops for which its lower levels were designed, bars, restaurants, bookstores, galleries, and spaces meant to bring together the technological interests of the younger generations and the industrial know-how of the older generations — a cohort well represented among the complex’s longtime tenants — and a highly Instagrammable rooftop.

No matter how closely Makercity Sewoon aligns with Kim’s original vision, it certainly serves the vision of Seoul’s current mayor Park Won-soon, who has premised his time in office upon turning the city away from its cycles of large-scale demolition and even larger-scale construction, and certainly away from the kind of projects commissioned by the Bulldozer — a nickname also applied to former president Lee Myung-bak during his mayoral term in the early 2000s. In other words, Park’s Seoul will break ground on no new megastructures, a term very much in architectural vogue when Kim was working on Sewoon Sangga in the mid-1960s.

Japanese architect and Pritzker laureate Maki Fumihiko had defined the concept of the megastructure a few years before as a large form that houses multiple functions and urban environments, a structure or set of interconnected structures that contains an entire city. Despite Kim’s disappointment with Sewoon Sangga, his fascination with the modernist promise of a city within a city endured for the next few years. In 1971 office submitted an even more exaggeratedly megastructural design proposal for the Pompidou Center in Paris, a commission that ultimately went to the international team of Renzo Piano, Richard Rogers and Gianfranco Franchini, who produced a megastructure of a different kind, one close to the exact aesthetic opposite of Sewoon Sangga.

Kim also distanced himself from the aesthetic of Sewoon Sangga in the early 1970s. The move manifests most strikingly in his design for the headquarters of his architectural firm, SPACE Group. The name reflects Kim’s central idea about craft: “Architecture is not about structures, but really about space,” as his protege (and onetime Seoul City Architect) Seung H-Sang, once put it. “The exterior of a building is just to cover up the space inside, and it is the space inside that’s the most important.” But it was the exterior of the SPACE Group building that gave Kim a highly visible chance to make good on his promise, after the Buyeo National Museum fiasco, to make a return to his Korean roots. He did it with brick, an unfashionable building material at the time, and brick that brings to mind jeondol, the fired clay blocks used for palaces and ritualistic structures during the centuries of the Joseon Dynasty prior to Japanese colonization.

Kim found a site for the SPACE Group Building in Bukchon, a neighborhood now known for its concentration of traditional (and pricey) hanok houses but which in the 1970s had even more of them than it does today. It was also the neighborhood where Kim spent his adolescence, his family having relocated there in 1943 from Chongjin in present-day North Korea. Any architecture critic would be tempted to draw parallels — though “parallels” may not be quite the geometrically appropriate term — between the winding, narrow alleys of Bukchon and the organically layered interior spaces of buildings like this one. He may well have made this still often-quoted observation with Bukchon in mind when he said, “The narrower a good street the better, and the wider a bad street the better.” (Though one might well question the second half of that statement if one has attempted to walk along a Gangnam thoroughfare like, say, Teheran-ro.)

Kim described the SPACE Group Building, into whose relatively modest height he fit 22 distinct floors, as a “bounded but infinite space.” So it remains even after a series of additions, including a new hanok outbuilding and a glass wing added by former SPACE Group CEO Jang Se-yang in 1997. But the firm no longer occupies the building that bears its name: after the SPACE Group’s bankruptcy in 2012, the Arario Museum took it over. The SPACE Group moved out, as did SPACE, Korea’s first arts-and-architecture magazine. Originally launched by Kim as SPACE Monthly (공간 월간) in 1966, SPACE still publishes today, in both Korean and English, standing as one of Kim’s most lasting achievements outside the built environment. In 1977, his work as an arts-and-culture impresario got him described as the “Lorenzo di Medici of Seoul” by Time magazine.

That appellation has stuck to Kim’s image over the decades, due not least to its having been applied by a Western publication (and to an architect who often seemed to build either for or with an eye toward the rest of the world). But the article’s headline described him, more amusingly and perhaps more accurately, as “The Swinging Lorenzo of Seoul.” And because of the generosity, even profligacy, that implies, Kim was no stranger to financial precariousness. The way he later remembered getting started on the SPACE Building sums up his attitude toward money matters: “I was so deep in debt to the bank that my house and the land for the SPACE Group Building had been up for auction several times. Even so, I started construction the building that’s on the land today. You can run up a debt of money, but you can neither borrow nor repay time: with that thought, I just went ahead and built.” The story brings to mind those of Park Chung-hee ordering the construction of an expressway across Korea and a subway system for Seoul, against his economists’ cries that the expense would bring about national ruin.

But Kim must have been paid at least somewhat handsomely whenever he turned back to nation-building, as he did when he designed the Seoul Olympic Stadium in 1977. As in the Freedom Center, he used curves to evoke Korean tradition, this time in ostensible imitation of a Joseon Dynasty porcelain vase. Though initially built to South Korea’s aim of staging the Asian Games in 1986, it became the prime venue when Seoul Hosted the Summer Olympics two years later. It has also, over the decades, occasionally hosted high-profile concerts, for the most part famous western acts — Michael Jackson, Elton John, Metallica, Paul McCartney — and more recently the homegrown boy-band BTS, who in recent years have more effectively promoted Korea abroad than anyone else.

“Architecture is poetry built of light and brick,” Kim once said, and the line encapsulates his approach to some of his most beloved buildings in Seoul, which he built with bricks in the late 1970s and early 80s. Several of these — now the Arko Art Museum, the Arko Art Theater, the Samtoh building, and others — stand together in an area called Daehak-ro, the former site of Seoul National University, resulting in the area’s reputation as a “living Kim Swoo-geun gallery.” Elsewhere Kim also designed several religious buildings with similar materials (and with their exteriors notably free of the red neon crosses that dot the Seoul skyline at night), including the Yangdeok Catholic Church and the Kyungdong Presbyterian Church. Kim modeled the latter after a pair of praying hands, with a first floor for the meeting of human and human, the second for the meeting of human and god, and the third for the meeting of human and nature.

Kim’s most famous work, at least by sheer volume of visitors, may be his least conspicuous: the subway station at Gyeongbokgung, the most visited palace in Seoul. The station won the Association of Korean Architects Award in 1986 — the same year that Kim died at 55, the age by which most architects have only just hit their stride. But if a typical person fails to complete one man’s share of work in seven decades of life, Kim Swoo Geun compensated by completing the work of four men in his 55 years — or so said Kim’s contemporary, the world-famous Korean video artist Paik Nam June. And if Kim completed the work of four men, he did it under the identities of many more: a Korean architect, a modernist, a traditionalist, a prodigy, a nation-builder, a publisher, a cultural impresario, a cultural ambassador — and even, in some sense, a “translator” of Japanese architecture.

Nobody interested in Korean architecture can have heard the news of Isozaki Arata’s Pritzker without thinking of Kim Swoo-geun. Not only were both born in 1931, and not only did both study at the University of Tokyo, but both began their careers working in styles not a world apart from one another: put Kim’s early concrete buildings, for example, up against the prefectural library Isozaki built in his hometown of Oita in the 1960s. Both took ideas of space articulated earlier by Frank Lloyd Wright — an architect who appreciated and was appreciated in return by Japan, the destruction of his Imperial Hotel in Tokyo notwithstanding — and made them their own. But what would Kim have done in his lost decades of architectural prime? There is the question of whether hould he have become the first Korean Pritzker winner, an accomplishment at which even his most architecture-blind countrymen would rejoice. But Isozaki’s MOCA, completed the year of Kim’s death, asks another one: what might he have built in Los Angeles?

Related Korea Blog posts:

Finding a New Seoul in the Old Buildings of Kim Swoo-geun, Architect of Modern Korea

Walking Deep Into Seoul With an Expert on the Korean Built Environment

Living the Vertical Life in Seoul

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.