Back in December, I wrote up a Seoul Book and Culture Club event featuring four Korean writers as a spectator. This past weekend, I experienced another as a participant, and specifically as the interviewer who talked with another group of Korean writers about their stories, all recently put out by ASIA Publishers in compact dual-language editions. I highly recommend these books (and all their predecessors in ASIA’s “K-Fiction” series) as learning tools to anyone studying the Korea language at an intermediate or advanced level. I also highly recommend, should the opportunity arise after reading the books, getting up on stage and talking to their authors about them.

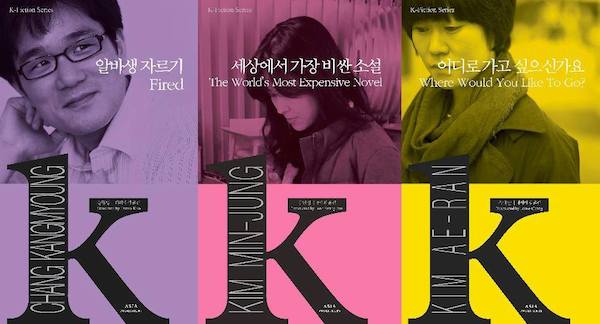

This time we had three writers: Chang Kangmyoung, author of Fired (알바생 자르기); Kim Min-jung, author of The World’s Most Expensive Novel (세상에서 가장 비싼 소설); and Kim Ae-ran, author of Where Would You Like to Go? (어디로 가고 싶으신가요). All three stories, so it seemed to me after reading them and considering them together, have to do with the condition of “young-ish” Koreans, those in their mid-twenties to mid-thirties who, while hardly kids, have for a variety of economic, societal, or personal reasons not quite made it to what the generation before them would have considered a full-fledged adult life. This sort of thing as provided fodder even in America for trend piece after hand-wringing trend piece, but the society of South Korea, a country that more recently came to the end of a much more dramatic period of growth, has felt it with special acuteness.

Chang Kangmyoung deals with this this most directly in Fired, which comes with its own nonfictional appendix explaining how the South Korean economy has changed with each generation. Hye-mi, a part-time front-desk worker at a mid-sized Korean company who turns up late, takes long lunches, spends hours on the internet clicking around travel and music sites, and never makes it to after-work company dinners. But rather than telling it from Hye-mi’s point of view, Chang makes a protagonist of Hye-mi’s supervisor, who at first feels sorry for her young-ish underling but then, when the aggravations built up, decides to get rid of her, running into a host of unexpected difficulties in the process.

I brought up, as the obvious comparison, Herman Melville’s “Bartleby the Scrivener”, another story of a young-ish character employed in an office but not performing the duties, responding to his boss’ every request with a now-household phrase: “I wound prefer not to.” But Hye-mi’s situation, Chang wasted no time pointing out, differs considerably from Bartleby’s: whereas the latter now stands as the literary personification of unwillingness, the former lives under a burden of inability, unable to commute to work quickly because she takes an old and breakdown-prone subway line from a distant satellite city, unable to get back from lunch in time because she has to use the hour to get treatment for an injured leg, unable to bring visitors refreshments because the office hasn’t provided anything with which to serve them properly.

(photo: Stephane Mot)

The novelist narrator of Kim Min-jung’s The Most Expensive Novel in the World lives in outwardly dissimilar but similarly stunted circumstances, still with her parents at the age of 34, $60,000 in debt from a literature PhD, and bringing in a yearly income of nothing at all. She can appease her mother, who watches closely over her always ready with a praiseful remark about her successful investor brother, only with the sound of the printer. (This, to me, represents the mindset of many Koreans who came up during the industry-and-development-obsessed 1960s and 70s, who probably can’t rest unless they hear some sort machine working away.) But despite not having yet published a full-length novel, she can at least call herself a novelist, not so much because of her daily writing habits — which she keeps up, more or less — but because she won a prize with a previous piece of fiction, the only way Korean society will grant a novelist the title.

Prefacing the question by remarking on how many hugely popular novelists in the West have never won a prize of any kind, I asked Kim why you have to jump that hurdle in Korea before anyone will acknowledge you as a novelist at all. She explained it in terms of the different conceptions of the role of the writer in the West and Korea (or indeed Asia): whereas a writer in the West may only have to write books and maybe — probably — teach students, people also look to writers in Korea for comment, both indirect and direct, on society itself. They must, in other words, fulfill the role of qualified “public intellectual” that America has, by now, specialized almost out of existence. And people want their public intellectuals, whether in the East or West, to have attained at least a certain age.

On top of that, the limited number of validating prizes for which Korean writers can compete means that it takes longer than elsewhere to make one’s debut (especially by comparison to America, the land of “30 under 30” lists). And so the circle of “young” novelists in Korea has seemingly widened to encompass anyone under the age of fifty. This makes the likes of Chang Kangmyoung, Kim Min-jung, and Kim Ae-ran fresh-faced youngsters indeed, though with with an average age somewhere in the mid-thirties (and all looking even more youthful than that, I should note), they make for ideal representatives of Korea’s “young-ish” generation, falling between the parents who enjoyed the secure gains of a growing economy and the kids in a slowing one who work odd jobs while dreaming of emigration. (One of Chang’s earlier novels bears the title 한국이 싫어서, or Because I Disliked Korea.)

Myeongji, the protagonist of Kim Ae-ran’s Where Would You Like to Go? has attained some of the trappings of a Korean middle-class existence, such as a full-time office job, a husband, the intent to have a baby, and the beginnings of an ability to make kimchi. But alas, in the middle of her first attempt at preparing the culture’s signature fermented cabbage, she suddenly gets a call informing her that her husband, a teacher, has drowned attempting to save the life of one of his students, an event which detaches her from the life she has established and eventually sends her into a self-imposed exile in Edinburgh. And even though Kim makes no mention of a boat, a class trip, or even any deaths apart the teacher’s and the student’s, the reader’s thoughts could hardly go anywhere but straight to the sinking of the Sewol in 2014, an incident widely seen as not just the failure of the older generations’ responsibility toward the younger, but also a terrible indictment of South Korea’s claim to membership in the first world.

Artifacts of Korea’s struggle to attain that status surface even in the story of Fired: when Eun-yeong, Hye-mi’s supervisor, eventually gives up trying to help and starts trying to fire what she sees as this intransigent albasaeng (알바생, a portmanteau of the words for “part-time job” and “student” that has come to signify a whole unstable quasi-caste), she comes up against a variety of labor laws — of which the seemingly unthinking Hye-mi can actually quote chapter and verse — that came into effect well after the country’s industrialization and without the knowledge of many of its employers. Hye-mi, at least for a time, proves unfireable, and she and Eun-yeong the prolonged but subtle grudge match only ends when the older woman pays off the younger one to defuse her intimated threats of a lawsuit.

Hye-mi can sue because her employers, in attempt to save money, never enrolled her in the company insurance programs — illegally, it turns out. Eun-yeong and those above her in the office, a local branch of a large German firm, know that they they must, at any cost, prevent their foreign overlords from finding out what has happened: “The Germans are really sensitive about this type of stuff. Basically, they don’t trust the Korean employees. They think that we secretly break the law and embezzle funds. And since working conditions are really important to them, they have separate supervisors for this type of stuff. That’s why to them, this is huge.”

I asked Chang about this curious co-existence between Korea’s national obsession with joining the ranks of highly developed countries and its entrenched resistance to following certain common practices of those countries. He put Germany on the long list of places he’s seen his homeland look toward and try to imitate as long as he can remember: first it was Japan, then America, then France, then Germany, and now the Scandinavian countries have come into fashion. He described Korea as less a developed country than one “being developed,” and — after clarifying repeatedly that he knew understood the controversial nature of this opinion — argued that Western-style capitalism and democracy represents the way forward not just for this country, but, adding in English after the interpreter finished translating his answer, “for all mankind.”

That may be, but as I couldn’t help adding, many visitors — even those from the countries long acknowledged as members of the first world — arrive in Seoul marveling at a level of development apparently so much higher than the one they came from. Especially to someone like me, coming from an America in a period of economic malaise and large-scale infrastructural decline, South Korea looks like the future, or at least the extreme present. On some level, I think the writers know it: Chang Kangmyoung has roots in Korea’s science-fiction community, Kim Ae-ran writes the most meaningful conversations of Where Would Like To Go? between her bereaved narrator and Siri on her iPhone, and Kim Min-jung’s The World’s Most Expensive Novel offers a vision of literature dependent on wealthy patrons and embedded advertisements. She takes it to a funny and grim extreme, but whatever shape the literature of Korea’s future takes, I trust this “young-ish” generation to write it intelligently.

You can follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.