“Whatever you do,” fellow foreigners here in Korea occasionally tell me, “don’t go on television.” Easy enough advice to follow, you’d think, though many Koreans, upon meeting a Korean-speaking non-Korean, almost automatically insist that they should go right before the cameras. Flattery in the absence of anything else to say aside, the response reflects a real viewer demand. Recent years have seen a flowering of shows about foreigners in Korea, and not just EBS’ documentation of the home and work lives of the various Canadians, Jamaicans, Vietnamese, and Russians who wind up married with children here. You can easily channel-surf your way to other shows, hit shows, that have made their foreigners into stars.

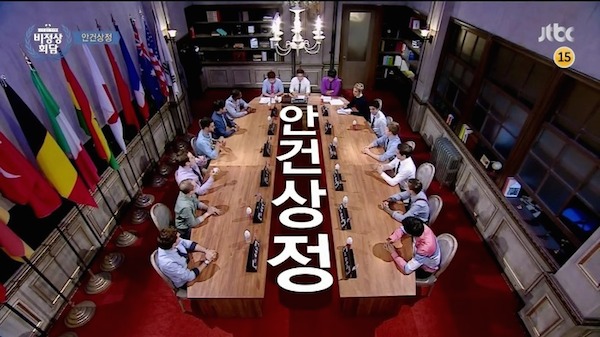

If you often fly on airlines that serve South Korea, you’ve probably noticed among their canned television a program with the curious title of Non-Summit, originally from the cable network JTBC. Pitched as a comedic G20 meeting, most of the show takes place around a U-shaped table. On its sides sit eleven or so men in their twenties and thirties, all of various non-Korean nationalities — English, Canadian, Japanese, Italian, Chinese, American, Belgian, French, and Australian on the 2014 debut. At its head sit three slightly older Korean men who preside each week over a discussion of current events in Korea as well as in the countries of the “representatives”, the more emotionally charged — whether in the nationalistic sense or in the realm of mild scandal — the better.

The episodes’ overarching issues range widely: fashion trends, the War on Terror, pre-marital cohabitation, the generation gap, sad pop songs. All these discussions, apart from the readings-out of each country’s news item under discussion, happen entirely in Korean. This by itself, even two years into the show’s run, constitutes a real element of novelty, since most of the foreigners who appeared on Korean television before had a patchy to nonexistent command of the language. Even Non-Summit‘s closest precedent, KBS’ all-foreign-women Global Talk Show, never seemed overly concerned with its panelists’ language ability. (Its Korean title 미녀들의 수다, or “Beautiful Women’s Chat,” sheds some light on its priorities.)

But Korea, as I’ve written here before, lags behind the rest of northeast Asia in foreigner integration, especially of the linguistic variety (the only kind of integration a foreigner, especially a Westerner, can really achieve here). A popular television show that features a group of them every week does its part to alleviate that condition, though that very popularity would seem to indicate that Korea, unlike Japan and China, hasn’t quite made it out of the stage where a foreigner can attain celebrity status by competently speaking the language. Dave Spector, known across Japan as “Dave-san,” put down stakes there in 1983; Mark Rowswell became the Chinese public’s beloved “Dashan” when he appeared on a 1988 New Year’s broadcast watched by 550 million people.

Non-Summit has come closest to creating a similar breakout personality in Tyler Rasch, the representative of America during its first two seasons. By background and inclination a quick and thorough language-learner, he seems, just like the mild-mannered Rowswell, to draw resentment from other foreigners as he does admiration from the locals, who invariably describe him as a better Korean speaker than they themselves. “It used to be that people in Korea would praise my Korean abilities. But now that so many foreigners fluent in Korean are appearing on TV, the mood has changed,” writes the film critic and longtime Seoul resident Darcy Paquet. “People may not say it out loud, but I know it’s true: in their heads, everyone is comparing me to Tyler.”

Clearly the smartest guy in the room — and one who certainly didn’t force the editors to cut creatively around his speaking deficiencies — during his time in the American seat, Rasch vacated it in June, leaving viewers to wonder who would hold up the show’s high level of discourse. But it makes me and his other foreigner fans consider a different question: what do you do after Non-Summit? Many non-Koreans here complain of having “hit a wall,” but most of them came to teach English and, having never learned Korean to a high level, can’t find a way out of the industry they never really meant to get into in the first place. Work in Korean media, no matter how acclaimed, may present a similar dead end; scratch the surface of half the foreign-language broadcasters here, and you’ll find something like desperation for a job back “home.”

At least they have endorsement deals. I’ve seen Rasch pop up in language-product ads on the internet, and just about equally famous Ghanian Non-Summit colleague Sam Okyere in ads on the subway. Okyere, who’s also moved on from the show, must also have wielded serious influence behind the scenes, since the producers seemed to allow only him to have a normal-looking hairstyle. Everyone else’s hair juts out and swoops around in all manner of ridiculous angles, the better to complement their flashy suits (often with chasm-like collar gaps) and glowing makeup — the dire aesthetic fate, perhaps, that inspires all those warnings about not submitting to the Korean televisual machine.

Or maybe they refer to the layers and layers of extra text and graphics applied, as in so many Korean television programs, to enliven the proceedings, underscoring slights and embarrassments, intensifying emotions, and hammering on the occasional mispronunciation. They also have a good deal of fun with the icons and traditional costumes of each representative’s country of origin, one of those practices that gets so many foreigners — mostly Westerners, and then mostly Americans — firing off accusations of insensitivity, condescension, racism, and what have you from the moment they arrive. But the show has also made an effort, against expectations, of introducing representatives from nations it could have overlooked, like Egypt, India, Mexico, and Iran.

It once had a Turk at the table — naturally, given the Turkish-South Korean special bond — but that didn’t work out so well. Over the first twenty or so episodes, Enes Kaya made his name as the show’s conservative loudmouth, referencing at every opportunity his devotion to family, respect for tradition, abstention from alcohol, and so on. An American viewer, witness to the constant disgracing of their own fire-and-brimstone preachers, homophobic politicians, and aggressively wholesome sportsmen, would have known exactly what to respect. But Korean viewers (the society’s dim view of its own sexual morality as revealed in novels and films notwithstanding) still haven’t fully recovered from the shock of revelation at the texts Kaya, already married to a Korean woman, exchanged with his girl (or one of his girls) on the side.

That degree of scrutiny provides another good reason not to go on Korean television, as does the fear of becoming what the expat-in-Asia parlance calls a “performing monkey.” Non-Summit doesn’t exactly downplay its freak-show angle: the Korean title, 비정상 회담, translates as “Abnormal Summit,” and the concept’s basic humor comes out of holding up anyone so patently eccentric as a Korean-speaking foreigner as a “representative” of anything. But I suspect that the success of these shows has less to do with the fascination of watching any particular foreigner than watching other Koreans interact with foreigners. (Non-Summit also brings on a steady supply of pop stars, actors, and other famous Koreans for its representatives to chat with.)

That fascination extends beyond the television screen. As one Korean friend (who happens to run an online Korean-teaching empire) put it, “If you’re a foreigner riding the subway with a Korean, every other Korean onboard is watching to see how that Korean is interacting with you.” Whatever the language of that interaction, the “audience” wants to observe how one of their own engages with, to use the academically fashionable term, the Other. And though you could probably live out your life in Seoul without once having to appeared on television, as for avoiding the subway… well, you’ll sooner learn to speak Korean like Tyler Rasch.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Multicultural Love and Its Discontents

You can read more of the Korea Blog here and follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.