Every visitor to Seoul sees Gwanghwamun Square, stretching as it does between two major tourist attractions: at its north end Gyeongbokgung, the palace that comes in near the top of every list of the city’s must-see destinations, and at its south end Cheonggyecheon, the former freeway overpass admired by urbanists the world over since its 2005 conversion into a long, idyllic public space. Gwanghwamun Square boasts statues of the two great heroes of Korean history as currently conceived: King Sejong the Great, who created the Korean alphabet in the mid-15th century, and Admiral Yi Sun-sin, who beat back the invading Japanese in the late 16th. But in itself, it isn’t much of a destination: whenever I’ve brought visitors there, indeed whenever I’ve set foot there myself, it’s always been on the way to somewhere else.

Despite its name, Gwanghwamun Square is nothing more than a pedestrian island in the middle of a major street, separated from the sidewalks by six lanes of traffic on either side. That’s actually an improvement on the old days, back when there wasn’t even an island: movies from the 1970s and 80s like Night Journey or Chilsu and Mansu show Admiral Yi standing alone in a sea of automobiles. But being cut off from the businesses along the street — not to mention a near-complete lack of seating and shade — has kept from Gwanghwamun Square the kind of vitality American and Asian travelers envy in the squares of old Europe. Having acknowledged the deficiencies of one of its central public spaces, the City of Seoul has lately commissioned plans for a redevelopment aiming to replace some of the traffic lanes and turn the island into something more resembling a genuine square. This process has involved gathering opinions from Seoulites, with a focus on groups not often consulted: the young, enthusiasts of alternative means of transit, the disabled, even foreigners.

Hence the invitation I received to participate in a “foreigner’s forum” on the future of Gwanghwamun Square. As the only American on the panel, I figured I could contribute by discussing the many less-than-ideal public spaces of Los Angeles. Everywhere in the world, I can get a laugh by mentioning the various “squares” designated all over the city by nailing signs with the names of notables — Billy Wilder at Sunset and La Brea, John Fante at Fifth and Grand, Dosan Ahn Chang Ho at Jefferson and Van Buren — over unaltered, practically automobile-only intersections. A more relevant example is to be found in Pershing Square, fatally flawed not because of its much-derided design but because of the cars constantly entering and exiting the garage beneath it. The more recently built Grand Park provides an even closer analog to Gwanghwamun Square, what with the streets slicing it apart and cutting it off from the surrounding institutions, City Hall and the Music Center in the former case, Gyeongbokgung and the Sejong Center for the Performing Arts in the latter.

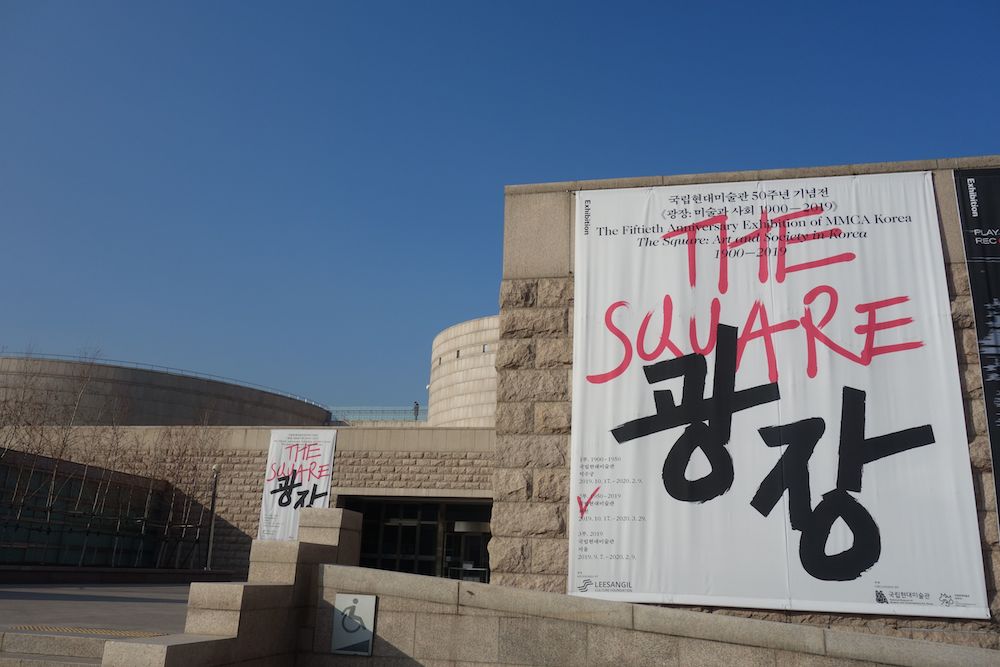

In 1965, the architect Charles Moore considered “where one would go in Los Angeles to have an effective revolution of the Latin American sort: presumably, that place would be the heart of the city.” But “if one took over some public square, some urban open space in Los Angeles, who would know?” In Seoul, by contrast, when a group wants to make their complaints heard, they air those complaints in Gwanghwamun Square: demanding an investigation into the sinking of the Sewol, bringing down former president Park Geun-hye, or boycotting Japan. In my experience, one kind of demonstration or another takes place there more evenings than not. Hence, despite its hundreds of participants, my near-failure to notice the one I passed last Friday night on the way from one branch of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (국립현대미술관) to another. I was revisiting The Square (광장), an ambitious exhibition celebrating the MMCA’s 50th anniversary, simultaneously held since October in its three locations in and outside of Seoul.

The MMCA was founded in 1969, an era by which South Korea’s full-bore industrialization had already given rise to a sizable middle class. As interesting as the half-century since then has been in this country, The Square has longer historical ambitions. Its first part, on view at the MMCA’s branch on the grounds of Deoksugung, the palace across from Seoul City Hall, covers the years 1900 to 1950. Its second part, at the MMCA in the administrative-center suburb of Gwacheon, covers 1950 to 2019. Its third part, back in Seoul at the MMCA’s main location next to Gyeongbokgung, focuses on the past year alone. Together they tell the story of the past 120 years in Korea through art, a story that begins early in the Japanese colonial period. It continues through World War II and national division, the Korean War, military dictatorship, the 1988 Olympics, conversion to democracy, the Asian Financial Crisis, and the World Cup. It ends with South Korea punching above its weight not just in the world economy but in world culture, a ranking that surprises Koreans as much as anyone else.

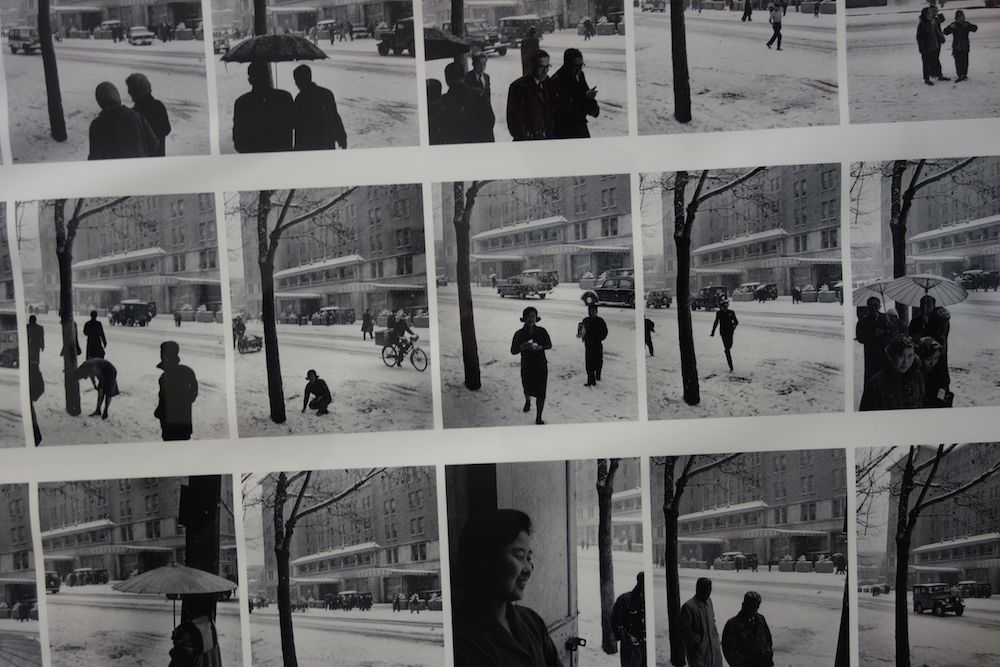

Across this historical sweep, the forms on display vary widely. The earliest works include reverential portraits of anti-Japanese agitators, screens painted with bamboo by exiled intellectuals, and publications of the colonial-period avant garde. There follow scenes of wartime chaos and misery, photographs of the developmental patchwork that was old Seoul, and attempts in various media to integrate (with various degrees of success) traditional Korean aesthetics with those of the West. From the 1960s and 70 come midcentury household appliances and their proud advertisements, and from the 1980s massively scaled tributes to the protestors of that decade as well as promotional materials for the Olympics (including a model of beloved tiger mascot Hodori). Representing recent decades are photographs, installations, and videos by and about Koreans looking both inward and outward — usually with a dim view of the homeland — as well as treatments of recent events like the Sewol and South Korea’s relationship with the North.

Many of the artists, such as the modernist painter Charles Park who spent 15 years of the 1930s and 40s with Ahn Chang Ho in Los Angeles, are little-known or forgotten. Others are Korean household names: Old Man Gobau creator Kim Seong-hwan, for instance, here represented not by his comics but his drawings of life amid the Korean War, or Kim Whanki, the first-generation abstract artist shaped by time spent in Tokyo, Paris, and New York. The Square‘s title references a well-known work of not visual but literary art, the eponymous 1960 novel by Choi In-hun. Like Yu Hyun-mok’s film Aimless Bullet and many other narrative works of that era (as well as most others) in South Korea, the book mounts an unsparing critique of Korean society. Its protagonist Myong-jun, a prisoner released after the Korean war, faces the choice of which Korea to be released into. But neither appeal to him, and he sees the failings of both in terms of “the Square,” the metaphorical public space in which the shape of a society is determined.

In South Korea’s wantonly abused Square, “excrement and garbage have just piled up. Things that should be everyone’s are selfishly taken for personal benefit.” When politicians enter, “they bring a sack, a hatchet, a shovel, and a mask to hide their faces.” But the other side of the 38th parallel, which promises revolutionary fervor but delivers only dead-eyed compliance, proves no more admirable. “The communists he met in the North were not the idealists he had imagined them to be before leaving South Korea,” writes Choi. “In the eyes of Myong-jun, South Korea was nothing but a Square for the people who did not exist, borrowing from Kierkegaard. The fanatical belief in the North was terrifying. But the total absence of faith in the South was equally hollow. Compared to North Korea, one merit of the Square of the South was that it allowed one the freedom to be corrupt and the freedom to be lazy.” Myong-jun ultimately desires to live in neither Korea, but a neutral “third country” — the one place his compatriots won’t allow him to go.

In their gift shops the MMCA sells not just a thick exhibition catalog for The Square but a whole book of short stories commissioned especially for the exhibition. The seven contributing writers — including Kim Sagwa, author of Mina, the rare Korean novel featuring an even more bitter protagonist than Myong-jun — all deal differently with the concept of the public square, deploying it in settings from an apartment complex to a mobile messaging app to Seoul Plaza, the real, physical square in front of City Hall. In recent years a temporary ice rink has been constructed on Seoul Plaza each winter — I went skating there just last week — but it also serves as a protest space: four years ago, not long after arriving in Korea, I wrote about an impressively branded and choreographed protest there over labor-law reform, agricultural free trade with China, and the Park Geun-hye government’s attempted history-textbook revisions.

Ignoring the role of protests would render incoherent a history of the past 120 years in Korea. So, to a similar extent, would ignoring the role of Koreans who leave Korea (for places such as, say, Los Angeles), exit being another kind of reaction to the shape society has taken. While undeniably present, neither of these themes dominate The Square, though the works’ undercurrent of dissatisfaction — dissatisfaction with a weakness before foreign powers, with the heavy inheritance of one’s own culture and the difficulty of assimilating the influences of others, with the rigors of economic development and its promises that have a way of not quite coming through, with one’s own opportunities in life or lack thereof — never runs far below the surface. But those who express such feelings in the public square, whether with protest, art, or literature, must believe that the country could have turned out differently, or still can turn out differently, or in any case remains a work in progress. This oblique sense of promise continues to manifest in Korean life today, less as any kind of optimism, per se, then as a sense that things can always change — up to and including, as will soon be demonstrated in the heart of Seoul, the square itself.

Related Korea Blog posts:

A Society of Screens: the Korea, and the World, Envisioned by Nam June Paik

Ways of Looking at Kim Swoo-geun, Korea’s Poet of Brick, Concrete, and Much Else Besides

Old Man Gobau, the Unflappable Comic-Strip Star Who Witnessed South Korean History

Factory Complex: How (But Not Why) Working Women Have it So Bad in Korea

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.