Many Western expatriates start feeling their days in Korea are numbered as soon as they become parents. “We’ll have to leave before the kid starts school,” I often hear; the combination of urgency and vagueness reminds me of Los Angeles parents insisting that one “just can’t” send one’s children to whichever local public school their address assigns them. Whether by leaving the country or by shelling for an international (in most cases, read: ersatz American) school, the Western parent — and increasingly, the Korean parent of means — instinctively avoids the Korean education system. What if the kids are subject to overly strict hierarchies? What if they don’t get enough English? What if they have to engage in “rote” and “uncreative” East Asian forms of learning?

Come off glazed and harried though they may, Korean students seem at least to internalize some knowledge in the classroom, which is more than I can say for myself or most of my classmates in the United States. The dreaded Suneung, Korea’s infamous do-or-die college entrance exam that for some families constitutes a reason to emigrate in itself, essentially tests one’s ability to memorize and, as Westerners might put it, “regurgitate” large amounts of information. But given the reliability of retention and recall as a proxy for general intelligence, the Suneung does a decent job as a sorting mechanism. Westerners who find that hard to believe also doubt the effectiveness of other unfamiliar Korean educational traditions: pilsa, for example, the practice of copying published texts out word-for-word by hand.

Just as I have yet to meet a single Korean unaware of pilsa, I have yet to come up with a proper English equivalent of the term itself. Some have suggested “transcription” or “copying,” but neither brings quite the right activity to mind. In Korean I’ve heard the task in which Herman Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener is supposed to be professionally engaged referred to as pilsa, an apt label insofar as most Americans’ response to the prospect of doing something like pilsa is that they’d prefer not to. But the practice isn’t completely unknown in the West, and in some quarters it’s become a routine suggestion to aspiring writers looking to hone their craft: take the circulation, in recent years, of stories about the pilsa-like practice of no less an icon of American letters than Hunter S. Thompson.

According Porter Bibb, Rolling Stone‘s first publisher and a friend of Thompson’s since high school, Thompson at first “chose, rather than writing original copy, to re-type books like The Great Gatsby and a lot of Norman Mailer, the Naked and the Dead, a lot of Hemingway. He would sit down there on an old typewriter and type every word of those books and he said, ‘I just want to feel what it feels like to write that well.'” As Thompson himself later put it to Charlie Rose, “If you type out somebody’s work, you learn a lot about it. Amazingly, it’s like music.” In Hunter S. Thompson: Fear, Loathing, and the Birth of Gonzo, biographer Kevin T. McEneaney writes of how Thompson began to re-type Gatsby while working as a copy boy at — and making use of the typewriters, ribbons, and paper that were property of — Time magazine.

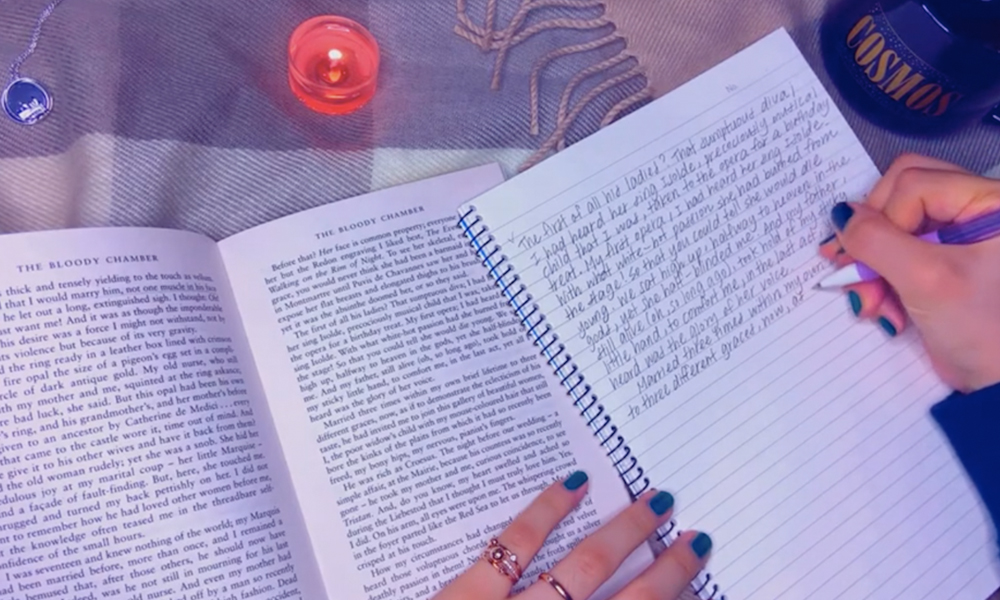

The young Thompson misappropriating office supplies from the country’s most stolid mainstream publication in order to craft what would become his “gonzo” prose style makes for an irresistible image. Yet true pilsa, to hear its Korean enthusiasts tell it, should be performed not on a keyboard but with a more traditional writing implement in hand. That recommendation is right there in the name, one that comes descended from the Chinese characters 筆寫, the first of which refers not even to a pen or pencil but a writing brush. In the 21st century only a thoroughly antiquarian pilsa practitioner would do it that way, but in the pilsa-oriented corner of Youtube, one finds plenty of discussion as to what sort of pens and notebooks produce the best results.

But what, exactly, are the best results? Even Westerners can easily understand pilsa as a means of improving one’s penmanship, and Westerners over a certain age may remember repetitively writing simple maxims down the pages of copybooks to that end in school. Rudyard Kipling had the foresight to warn us of the eternal return of those copybooks’ gods, but he surely couldn’t have imagined the form of modern Korean pilsa culture, whose Instagrammers carefully arrange photographs of their pens, notebooks, and copying material. There are even real-life groups dedicated to pilsa — I remember one from Peter Cat, the Haruki Murakami-themed book cafe I wrote about here in 2017 — formed on the theory that doing it alongside others keeps it turning into mindless labor.

Improved handwriting motivates serious pilsa enthusiasts no more than the prospect of improved keyboard technique motivated Thompson to type out the work of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, and Norman Mailer. Re-writing the work of another writer helps one internalize the characteristics of that writer’s style, but also to more thoroughly understand the work itself. The smoothness of The Great Gatsby‘s surface almost encourages the casual reader’s eye to glide right over the fine-tuned mechanics of Fitzgerald’s prose. In America and Korea alike, many readers acknowledge the book as a masterpiece despite never quite sensing what makes it one, not least because they read it too fast. Pilsa slows the process down, forcing the reader to consider each and every word.

Pilsa is in this way as much a reading-enriching technique as a writing-enriching technique. But as writer, Youtuber, and pilsa evangelist Kim Si-hyun emphasizes, deliberately re-writing examples of masterful language use can enhance the practitioner’s verbal expressiveness on all fronts, not just on the page but in conversation as well. She and other pilsa-savvy personalities seem broadly to agree on the range of benefits the practice has to offer, which extends to a meditative clearing and relaxation of the mind. (Pilsa Youtube has also, of course, produced its own ASMR videos.) There are disagreements about such issues as whether pilsa absolutely requires pen and paper or whether a keyboard and screen will suffice, or whether it’s best to re-write entire books or just passages. But few pilsa advocates fail to emphasize the importance of making a steady, consistent habit of it.

And so, in my fifth year in Korea, I’ve incorporated a pilsa routine into my own life. What sold me wasn’t the promise of further mastery of my native language (though given my profession, it behooves me to pursue that), but of a less shaky grasp on the language that surrounds me — and that fascinated me enough to make me want to live here in the first place. Everyday conversation and reading have taken me some distance, but nowhere near as far as I want to go; the confidence that I can now more or less get my point across in Korean only underscores the awareness of my inability to do it with any genuine articulacy. There being no Korean writer whose prose I admire more than Kim Hoon, whom I introduced here on the Korea Blog earlier this year, I’ve been re-writing a few pages of his essays every day.

This attempt to learn Kim’s sentence construction with my body, to borrow a Korean expression, has succeeded to the extent that I’ve heard his style echoed in my own Korean writing. What it will do for the kind of Korean I speak is another matter: I still remind myself of the protagonist of J.M. Coetzee’s “A House in Spain,” a foreigner who speaks Spanish “of a hesitant, bookish variety.” And as the living Western novelist whose prose I find most compelling, Coetzee was the natural choice when I more recently tried my hand at English pilsa. In both languages, the practice has proven satisfying enough that I’m considering adding a third: why not Spanish, using the stories of Jorge Luis Borges? Still, my enthusiasm hasn’t yet grown excessive enough to use pilsa-specific pens and notebooks instead of my laptop. If I buy a brush, I’ll have clearly gone over the edge.

Top image source: 엔비의 비밀공간

Related Korea Blog posts:

Why Do Koreans Love Herman Hesse’s Demian Above All Other Western Novels?

Everything Turns into ASMR in Korea, Even Cultural Heritage

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.