When I want to learn about a city, whether researching it on the internet or stepping out into it in reality, I first look to its subway. It might surprise you how much you can infer about the overall personality of any given metropolis just from riding its trains, be that metropolis Los Angeles (incomplete and inconsistent, but still new and promising) or San Francisco (charming and infuriating in equal measure), New York (often old and dirty, but nevertheless an attraction for all walks of life) or London (highly serviceable, as long as you can enjoy grumbling about it), Mexico City (lively, brightly colored, enjoyably strange, and subject to sudden dysfunction) or Copenhagen (expensive).

I’ve ridden a good deal of urban transit in my time, none superior, thus far, to Seoul’s. Angelenos, who can count themselves as having a good day if their train shows up within fifteen minutes — assuming they need to go someplace a train actually goes, and assuming they know their city’s rail network exists in the first place — can only marvel at not just the system’s range, frequency, and cleanliness, but a host of features they’d never dared imagine: unbroken cell and wi-fi signals, displays that map the next few trains on the way in accurate real time, heated seats, and a variety of shops and cafés, or at least decently stocked stalls and vending machines (as well as non-horrifying bathrooms, the one true marker of civilization) in every station.

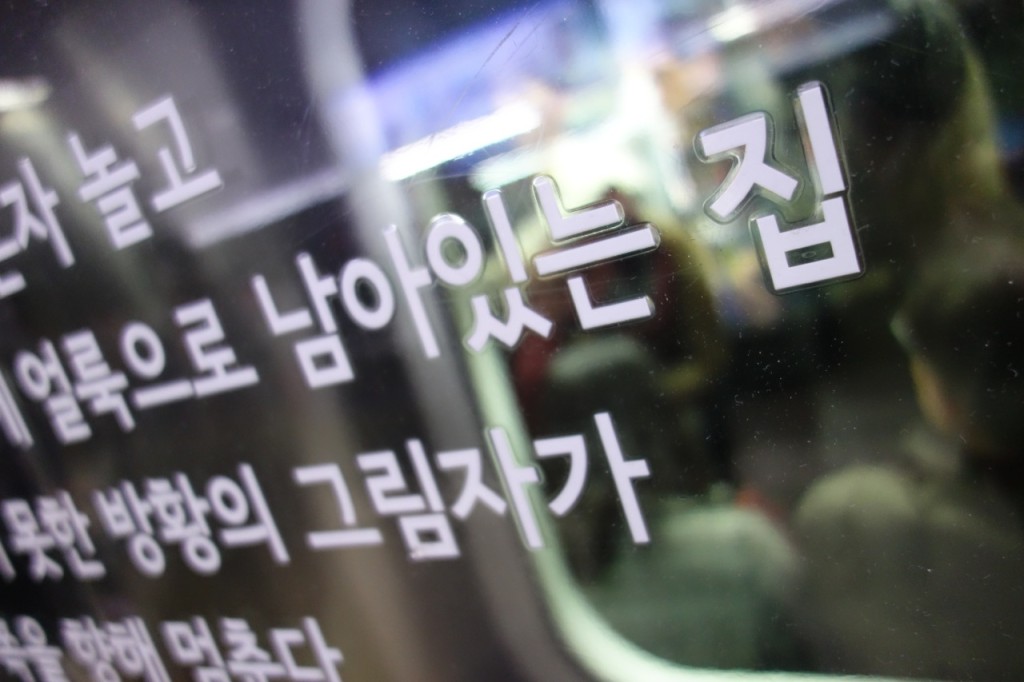

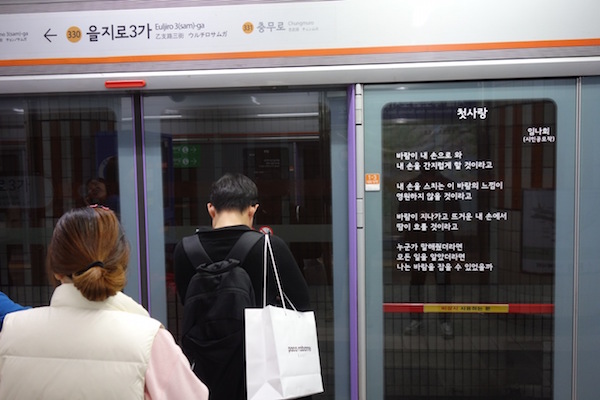

Once they adjust to all that, they might then notice, especially if they study the Korean language, how often they see poetry during their short waits for trains. And I don’t mean that metaphorically, as in the “poetry” of bustling, well-orchestrated urban life or what have you — I mean it literally, as in actual poems put up for everyone to read. The program that did it began in 2008, ostensibly to provide the harried citizens of Seoul with opportunities to pause and reflect amid all their underground to-ing and fro-ing. Today, theses poems have made their way up in nearly 5,000 locations in about 300 different stations.

The selection committee assembled by this subway poetry program have tweaked it over the years, introducing such refinements as tailoring the selection of poems thematically, in each station, to the surrounding neighborhood: poems to do with to youth at the Children’s Grand Park station, China at the Daerim station (center of Seoul’s Chinese population), Japan at the Ichon station (center of its Japanese population), America, England, and Nigeria at the Itaewon station (next to the American army base, and thus a kind of English-speaking enclave), and France at the Express Bus Terminal Station (near the Seoul headquarters of various French companies and the city’s biggest French school, and thus a place where, surreally, you hear French daily spoken on the street).

In Hong Sangsoo‘s Hahaha (하하하), a floundering film director attempts to win over a girl by writing her a few lines of verse about the moment he first saw her. “Everyone writes poems,” she responds, unimpressed. “I do,” she adds, “and so does he” — the boyfriend she already has, a poet by profession. Hahaha came out at just about the same time as Lee Chang-dong’s Poetry (시), the story of a small-town grandmother who decides to start writing poems in the early stages of Alzheimer’s, now one of the most acclaimed works of modern Korean cinema. People I ask for suggestions of Korean-language reading material often bring up books of poetry first.

So it seems that Koreans, in the main, don’t find poetry as marginal or even off-putting as the reputations of Americans suggest we do. In fact, I’ve heard many who know argue that the true heart of Korean literature lies less in novels, still a relatively new form here that in some ways hasn’t fully “taken,” than in short stories, and less in short stories than in poems. So it makes sense that, if Seoul wants to introduce literary moments into the long days of its commuters, it would use subway-station poetry as the tool with which to do it. (Although I could see Grenoble-style story vending machines potentially making inroads here too.)

All this nevertheless has its discontents. Some cultural critics have voiced the opinion that the poems selected, whether from poets living or dead, famous members of the canon or contest-winning everyday citizens, tend a bit too far toward the simplistic to represent the form at its best. That may be, though I have to admit that, while my command of the Korean language allows me to read them, the point where I can confidently evaluate them remains far in the future. (I can’t help but notice, however, a certain prevalence of blowing wind, blooming flowers, and things happening under moonlight.)

Whatever their literary merits, these poems always appear on one kind of surface in the stations: their “screen doors,” glass walls between platform and track with portals that automatically open when the doors of an arriving train align with them. This at first looks like just one more technological feature that puts the safety and comfort of Seoul’s subway so far ahead of the others, but then you realize why the biggest city in South Korea, whose suicide rate floats around number one in the world (vying with the likes of Guyana and Lithuania), needed them: if they didn’t block the way, you’d see a lot more people jumping in front of the trains.

But none of this will sink too deeply in with a first-time visitor who doesn’t yet know much about Korea, whose experience will probably have more to do with absorbing the richly incomprehensible social, technological, linguistic, and graphical world around them. In that perceptual environment, the poetry and the dozens of ever-changing advertisements surrounding it — for coffee, for cellphone games, for a popular matchmaking service called Duo — merge into one intense and essentially undifferentiated visual substance. I get a little bit of that experience myself whenever I go to Japan, where my tendency to forget the Chinese characters they use there renders me a borderline illiterate.

Still, I haven’t grown so adept at Korean that I can ignore either the poetry or the advertisements around me as I wait for the train; if I don’t read them, I might lose out on the valuable opportunity to learn a new word or expression (even for something other than moonlight). When you read ad copy and poetry in the same way, you soon start to see the former as a species of the latter. This, for me, holds especially true with the latest round of industrial-sized illuminated posters for that matchmaking company, which, though I doubt I have any future as a translator of verse, have offered me plenty of chances to try my hand:

Someone who put work before love

Someone who wasn’t ready

Someone who believed they were fine alone

Someone who just liked their freedom

Get me married, Duo

You can follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.