I started writing the Los Angeles Review of Books Korea Blog on December 4th of last year, just three weeks after moving to Seoul from Los Angeles. One of my first posts covered a protest in Seoul Square; once of the most recent covered a series of demonstrations over the course of weeks that eventually brought up to a million citizens downtown to demand the resignation of President Park Geun-hye, the announcement of whose impeachment came just this past Friday. I’ll certainly be sticking around to see what happens next.

The year has proven stimulating politically but also culturally, what with events like novelist Han Kang and translator Deborah Smith winning the Man Booker International Prize for The Vegetarian. Charles Montgomery, who joined the Korea Blog after spending seven years teaching Korean literature in translation at Seoul’s Dongguk University, wrote about the victory and has since begun an ongoing serialization of his book-in-progress The Explorer’s History of Korean Fiction in Translation, the most recent installment of which you can read here.

Below you’ll find a selection of twelve of my essays from the Korea Blog’s first year, whose subjects range from Korea’s aforementioned protests to its educational culture to its cosmetic surgery to its art and architecture to its urban life to its Mexican food. It should provide something of a primer to readers new to the Korea Blog, but also a review of surfaces scratched. I look forward to going ever deeper into the literature, cinema, current events, and daily life of this fascinating country in the Korea Blog’s second year. As always, 읽어 주셔서 감사합니다.

Why I Left Los Angeles for Seoul: “In the 21st century, America and Korea have, to some extent, switched roles: the former now looks a bit shambolic compared to the latter, and the latter, on the whole, still regards the future (despite much hand-wringing over the slowdown in the staggeringly rapid economic growth of past decades) as a good thing. I haven’t met an American who considers the future a good thing in years. A British friend here, a notable writer of books on Korea, felt just the same about his homeland when he left it in the early 1980s: ‘But I found that in Korea,’ he said, ‘I had a spring in my step.’ That’s not to say that the darker aspects of Korean life — the all-pervading culture of hierarchy, the shockingly high suicide rate, the major disaster every twenty years or so — can’t also take the spring out of your step.”

Protest, Korean-Style: “Longtime Korea-watchers tend to view the country not as a system of laws but of social relations, a framework which makes it easier to understand an environment where, as The Koreans author Michael Breen puts it, the opposition will ‘simply oppose and hinder government in whatever way it can, without bothering to develop rational argument,’ where parties form and dissolve as nothing more than ‘a gesture to democracy in an authoritarian political culture.’ Democracy for Koreans, as much now as when the last edition of The Koreans came out in 2004, ‘means they can elect their leader and hold him accountable. But they still do not see their political leaders as their representatives. There is still a view that leaders are wrong, corrupt and working against the interests of the people.’ I might add that, even though I didn’t dodge any rocks or breathe any tear gas this time around, that mistrust still goes both ways.”

Reach for the SKY: “Sometimes Koreans look surprised when they realize that I don’t give the proverbial two shits about where they went to school, or when I tell them that not every American student who could get into Harvard applies to it (or even considers it), or when I express admiration for those who didn’t go to college at all. We’ve certainly got our Ivy-League-or-bust types, I try to tell them, but the savviest American students think more in terms of finding the one college out of the possible many that best suits their personality and desires on a variety of axes: academic focus, but also sports, location, social life, architecture, food, exercise facilities, selection of arcade games, and so on. But that, in the main, doesn’t figure into a college-applying Korean high school student’s calculus: they study the hardest they can, get the highest test scores they can, and, no matter their set of interests, go the ‘best’ college they can — grappling with no ambiguity about which one that is.”

Looking for Mexican Food in Seoul: “Life in Los Angeles did give me the sense, though, that not every Korean who goes to America returns with all the wrong ideas about Mexican food reinforced. (One Korean friend, now a five-year resident of Los Angeles, cringes with embarrassment at the memory of a ‘Mexican’ dinner she once had with her high school pals back in Seoul, all thinking themselves the height of sophistication as they dropped ridiculous amounts of money on sodden enchiladas and tortilla chips.) Most of the Koreans I met there seemed to if not frequent then at least have some experience eating at El Taurino, the big all-night taco joint a few miles up Hoover Street from USC. This struck me as coincidental enough, but they also all called it by the same name: not El Taurino, but 후버타코, or hoobeo tako — ‘Hoover Taco.’”

Living the Vertical Life in Seoul: “Why do so many of us Westerners fear and loathe the vertical life? I don’t, so I can hardly find my way to the answer through introspection, but if I did, I suppose I wouldn’t have moved to Seoul in the first place. Seemingly every few weeks I meet someone who has the exact same memory about when they first arrived in the city: ‘My first apartment building had more people in it than my entire hometown.’ You can still find a place to live in a structure under ten stories, but sometimes I wonder how long that will last, given the number of cranes every day visible hard at work on the skyline. They’re building what I think of as, for better or for worse, Seoul’s architectural signature: forests of ten, twenty, thirty identical (or almost identical) 600-foot-ish towers, differentiated mainly by the three-digit numbers stamped on their outer walls.”

Ways of Seeing Korean Plastic Surgery: “The subject of cosmetic surgery in Korea comes so laden with baggage and cliché that, on one level, I haven’t really wanted to write about it; but on another level, some of the questions I consider most interesting never really get asked. At the top of the list: what about Korean plastic surgery, exactly, bothers Westerners so much? Different Westerners have different theories. Some think it has to do with a perceived hypocrisy, in that the longer a non-Korean lives here, the more of the glories of the Korean race that non-Korean will have heard implicitly or explicitly trumpeted. So why, they sarcastically wonder, does this world-beatingly superior people so badly need the assistance of cosmetic surgeons?”

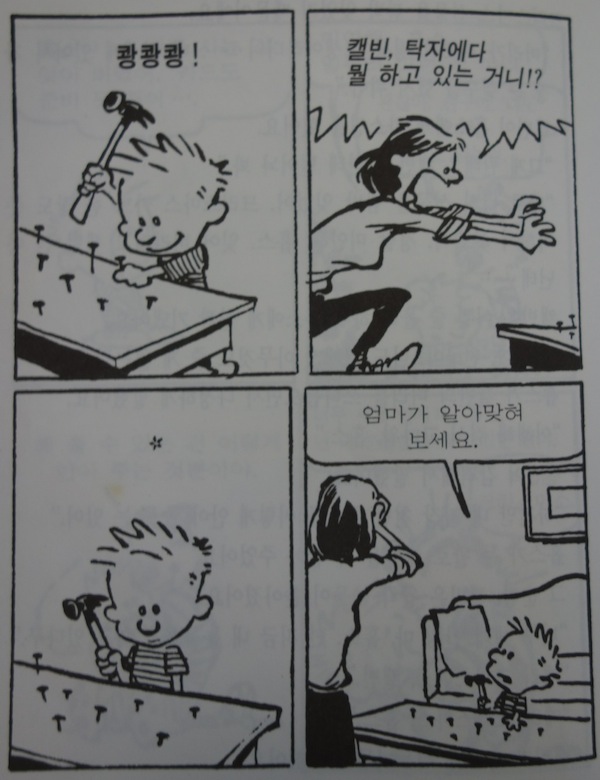

Reading Calvin and Hobbes in Korea: “This particular interpretation of Calvin and Hobbes plays fast and loose enough to fumble much of what makes the strip compelling in the first place, such as Hobbes’ deliberately ambiguous existential state, suspended eternally between stuffed doll, imaginary friend, and conscious being; the introduction to the Calvin and Hobbes Comic Reader flatly describes him as a toy that comes to life whenever only Calvin is around. But larger points remain intact: in Calvin and Hobbes, as the book’s afterword emphasizes to its Korean readers, ‘despite the different language and customs of this faraway country’s children’s story, you see yourself reflected.’ And somewhere in there I see my much younger self, often not quite grasping the language, but nevertheless keeping at it, enjoying the process enough now not to worry too much about a payoff later.”

Korea’s English Fever, or English Cancer?: “The expectation that all Koreans should speak English, and that no non-Koreans speak Korean, does more than its part to discourage the study of an already difficult language. Ironically, foreigners might well have an easier time of it if Korea subjected us to a Japanese-style (or stiffer still, Chinese-style) expectation of, over time, at least a certain level of conversational proficiency. It would certainly better suit the kind of strong country South Korea has become, strong enough to attract outsiders willing to learn its language rather than fall all over itself to learn a language of the outsiders. In an article on Korea’s thus far unfilfilled aspiration for a Nobel Prize in Literature, the New Yorker’s Mythli G. Rao quoted a Korean ‘literature enthusiast’ as saying that ‘I think the Nobel committee needs to learn Korean first.’ Some readers laughed at that, but I can’t say I totally disagree.”

A Society of Screens: “Video monitors started appearing on Seoul’s subway trains long before I arrived here. More video monitors — or, to be precise, old televisions — started appearing on those video monitors a few months ago, announcing a big show of the work of video artist Nam June Paik. (Paik made his name in the West, literally, with not just unconventional Romanization but a Western-style re-ordering that put his given name first and family name second.) The straightforwardly titled Paik Nam June Show (백남준 쇼), which runs through October at Seoul’s Dongdaemun Design Plaza, commemorates the tenth anniversary of the death of the most creative old-television enthusiast ever to live, as well as, for a time, the most famous Korean artist — and quite possibly the most famous Korean — in the world.”

Watching Korea Develop Through Sixty Years of Commercials: “These commercials not only show a Korea modernizing fast, they show a Korea modernizing too fast to do so on its own terms. Logographic Chinese characters vanish from the screen in a matter of years. Visual references to cowboys, cobblestone streets, and the Statue of Liberty turn into ersatz Western brands of jeans and ‘France style wine,’ followed by genuinely Western brands like Lacoste, Del Monte, J. Press (though the Japanese had bought it that quintessentially American outfitter whole by then) and the empire of Coca-Cola. Red bean ice cream bars, squid chips, and anchovy powder give way to boom boxes, sneakers, and Northwest Orient flights to Los Angeles, Seattle, and Chicago.”

Finding a New Seoul in the Old Buildings of Kim Swoo-geun, Architect of Modern Korea: “The kilometer-long linear development, which stretches across blocks and blocks of downtown Seoul, didn’t take long to draw disdain as a ‘concrete monstrosity’ (or the Korean-language equivalent thereof). ‘The phrase reverberates,’ says defender of British brutalism Jonathan Meades in his documentary Concrete Poetry of that now-standard architectural slur. ‘Any modest, self-effacing newspaper columnist can be sure that he will please readers with the same ready-made formula. For, as we all know, concrete monstrosities are culpable of virtually everything: they promote every known social ill, and many which have yet to be revealed.’ Though it does contain plenty of concrete, Seun Sangga is, of course, not British, nor is it exactly a work of brutalism. We could, perhaps, call it a work of pure developmentalism, erected as both a symbol of and a contribution to to the country’s fast-growing postwar economy.”

Anti-Trump Protests, Anti-Park Protests, and the Koreanization of American Politics: “From across the Pacific Ocean, the triumph of The Donald looked to me if not inevitable, then at least highly probable. For all its bluntness and disorganization, his campaign had by far a greater resonance with its enthusiastic target audience that Clinton’s had with its own comparatively ambivalent one. Take, to name just one element, the slogan ‘Make America Great Again,’ a brilliantly simple encapsulation of the longing it turns out that no small part of the country feels for a period of postwar economic growth and perceived class mobility — or, if you prefer, of being the only non-impoverished nation on Earth — that has now taken on a quasi-mythic quality. Park, daughter of the developmentalist strongman Park Chung-hee who ran South Korea for eighteen years and oversaw the country’s transformation from one of the world’s poorest into an unprecedented economic success story, might as well have run on the slogan ‘Make South Korea Great Again.’”

You can read more of the Korea Blog here and follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.