Twenty to one — you often hear that ratio brought up in discussions of Paju Book City, in which, so the legend has it, twenty books reside for every human being. That exact number has to have origins in the art of guesstimation, but still, it gets the point across. As its name might suggest, Paju Book City is dedicated to one set of purposes above all else: the printing, publishing, distribution, sale, purchase, and consumption of the printed word. But its builders have also pitched it as “a City to Recover Lost Humanity,” presumably the humanity so many state-of-Korea-bemoaners see as having been mercilessly wrung out of the country by its rapid and deep industrialization of the second half of the twentieth century, disfiguring the country with the uncouth, disorderly urban landscapes left in its wake.

Paju Book City’s English-language brochure gives you an idea of the emotions behind the project: “Cities filled with disorganized urban planning, chaotic road networks and buildings and a welter of signboards directly reflect our distorted life. Such distorted urban scenes give negative impact on our already arduous life, creating a vicious circle, which exacerbates us ceaselessly. Why was such an urban shambles created? When did such disordered architecture and urban planning come to us? It is because we lost the sense of common ground and value.”

Though the text adds that this happens in “any cities of Korea,” it takes no great feat of mind-reading to understand which distorted, signboard-weltered, ceaselessly exacerbating urban scene, exactly, the writer had in mind. And so Seoulites seeking a restorative dose of humanity can simply catch a bus, ride for between 40 and 80 minutes, traffic depending, and step out into this city purpose-built to provide it.

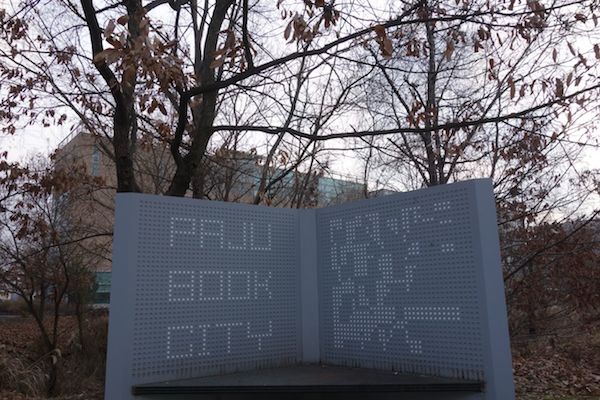

First proposed in the 1980s, planned and constructed in the 1990s, and opened in stages in the 2000s, Paju Book City occupies a bit of the copious amounts of land available in Paju, a former military area just south of the North Korean border. Its recent development and the wide-open space available for that development allowed for a kind of planning unthinkable in the capital: the kind of planning that can divide the city up into “publishing districts,” “printing districts,” and “support districts,” that can lay down stiff architectural guidelines, and that can try to replicate the qualities Wales’ tiny “book town” of Hay-on-Wye.

On some levels, Paju Book City would seem to make a ripe target of ridicule, especially in the contrast between the grandness of its self-description and the modestness of its real existence as a single-industry suburb, and a remote one at that. But I still find it an intriguing place to visit, as do many Korean tourists. Come on a weekend and it may at first seem completely uninhabited, its many publishing company offices (the firms having received strong encouragement to relocate there, or at least open a branch) and scattering of art galleries shuttered, but the closer you get to the the central Asia Publication Culture & Information Center complex, the more signs of life you see.

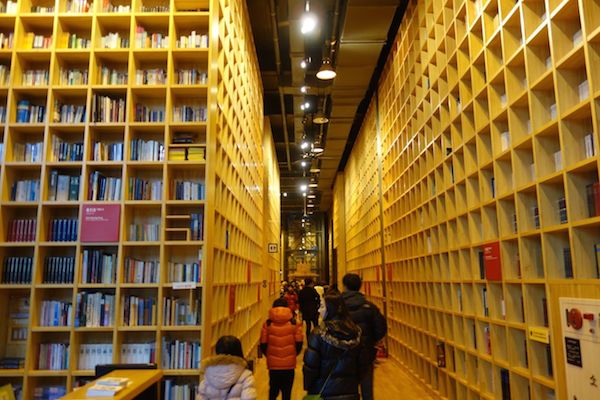

The beating heart of Paju Book City takes the form of its Forest of Wisdom, a 24-hour library stocked to the ceiling with hundreds of thousands of books donated for anyone to read and staffed by ladder-climbing volunteer “book recommenders” (권독사). Weekends see the dozens and dozens of tables in its cafe packed by readers, many of them families with young children. In its capacity as something of a theme park of letters, Paju Book City also offers a attractions geared directly toward youngsters, such as a Pinocchio Museum containing, for whatever reason, a Paddington Bear-themed gift shop.

Adults in a more soul-searching mood can opt for a visit to Café Hesse, one of quite a few coffee shops in Paju Book City, but the only one inspired by the author of Siddhartha, Demian (an oddly popular novel here in Korea), and Steppenwolf. Other book cafés have different themes and specialties — not that their drink menus vary much — but all of them make use of the space afforded them in this accommodating location to surround their customers with as many volumes as possible. In a sense, the coffee comes free; you just pay to drink it in a space filled with books.

Korean book culture has an aesthetic dimension that I haven’t noticed to quite the same extent in American book culture, whose products, on the whole, feel more generically assembled. Plenty of specialty presses exist in the West which take great care with their design, their paper, their binding, and so on — that take books seriously as objects, in other words — but that sensibility seems to extend farther across the smaller publishing landscape of Korea. At some point, of course, this can get ridiculous: “Why do I need to know the quality of the ink on my chick lit?” a Korean friend once rhetorically asked after I praised the bookmaking practices of her homeland.

Without wanting to overstate the point, I get the sense that books have retained a certain talismanic power in Korea, this most internet-connected of all modern societies. Koreans may not regard themselves, in the main, as intellectuals (I often think of the story of a foreigner who came to study Korean thought, only to have the people he met look quizzically at him and respond, “But we don’t have any thought”), but the idea that you might get an intellectual charge merely from the presence of books still has some currency here. The same notion no doubt got all those midcentury American households buying the complete set of Mortimer Adler’s Great Books of the Western World.

Many of those color-coded copies of Homer, Thucydides, Shakespeare, Gibbon, and Ibsen went unread, but they certainly contributed something to the décor. Paju Book City’s visitors really do seem to enjoy reading the books they have pulled off the shelves in the Forest of Wisdom, and they buy books from the nearby dealers with even greater fervor. Even those who don’t care about reading at all, or foreigners with no knowledge of the Korean language, can spend a fun day in this highly explorable, conceptually unusual, and — what with all the specially commissioned sculpture and architecture — visually fascinating place. I enjoy Korean books myself, but when when my own time comes to return to Seoul, I have to admit I feel ready to be exacerbated.

You can follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook. Catch up on the Korea Blog’s archives here.