It pleased me to watch Wonder Wheel, Woody Allen’s most recent film, at one of my favorite art houses in Seoul. Though hardly an Allen devotee — I’ll probably never get around to a good third of his filmography — I wouldn’t have enjoyed quite the same freedom, back in America, from the expectation to interrogate the morality of my viewership. “It would make life easier if Woody Allen’s movies were as easy and as right to condemn as his behavior,” declares the New Yorker‘s Richard Brody in his own piece on the picture. “But that’s not my experience of his movies, and this makes it difficult both to watch and to write about them,” as he has done, unfailingly, with “considered queasiness.”

Those two words also describe the feeling with which, from the other side of the Pacific, I’ve watched the movement that has made, or attempted to make, Allen into a pariah, including but hardly limited to the sordid combing-through of his work (and even his archives) for evidence of deviant desires. It brings to mind my reaction to another American movie I watched in Korea, the still-untainted (but also less artistically respected) Cameron Crowe’s Jerry Maguire, which I happened to catch on television not long before the floodgates of sexual-misconduct accusation opened onto Hollywood. Despite its place in the zeitgeist, I’d never actually seen it before, and I found myself astonished by the distance between its depiction of American life and the reality of American life today: the 1990s it portrays looks much closer to the 1950s than the 2010s.

When I brought this up to a friend who also grew up in America in that era, he pointed out the seemingly total disappearance of moral panics. Back then they’d been so common, and sparked by what now look like the most trivial phenomena: violent video games, “explicit lyrics,” a too-irreverent quip on the part of Bart Simpson. “A moral panic is always a reaction to something that has been there all along but has evaded attention — until a particular crime captures the public imagination,” wrote Masha Gessen, also in the New Yorker, late last year. “Sex panics in the past have begun with actual crimes but led to outsize penalties and, more importantly, to a generalized sense of danger. The object of fear in America’s recent sex panics is the sexual predator, a concept that took hold in the nineteen-nineties.”

Most of the sexual predators so labeled by the current sex panic Gessen describes have passed their prime, and for many of them, from known brutes like Harvey Weinstein to more vaguely disreputable figures like Kevin Spacey, that prime came in the 90s. The traditional media, at that time, also enjoyed much more robust health than it does now: its newfound willingness to name and shame 24 hours a day may look like a long-overdue reckoning, but it also, from a distance, looks like the frenzy of a mortally wounded beast, lashing out in any manner than might keep it alive one moment longer. (Sex, crime, and above all sex crime: the maxim about how to sell papers has held firm since the industry’s inception, and will until its demise.)

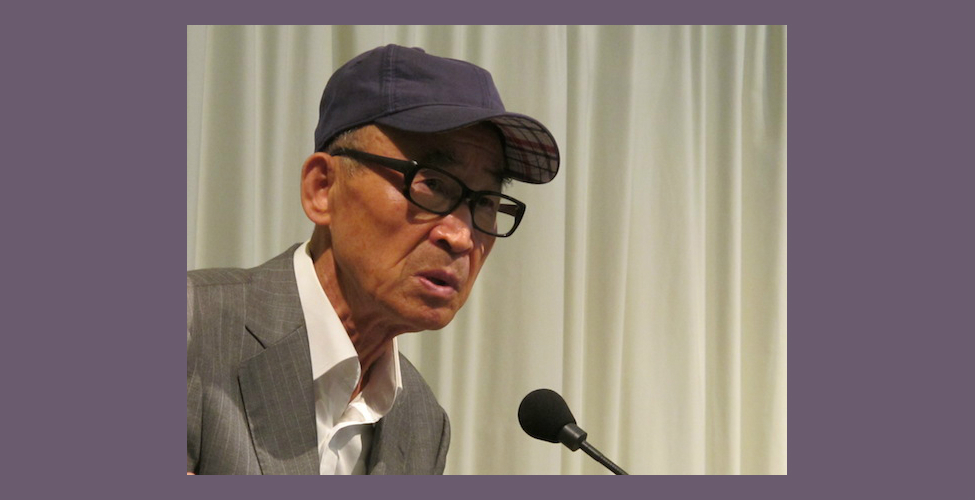

The purge has now managed to work its way down to men of letters: over the past couple of weeks, for example, a storm of Twitter demands has gathered for the head of former darling of Native American literature Sherman Alexie. The world of Korean literature has already experienced its own, more dramatic decapitation: the sudden and apparently society-wide repudiation of poet Ko Un, long regarded as Korea’s best hope for a Nobel Prize. It happened a few months after the publication of Choi Young-mi’s “The Beast,” a poem calling out “En,” a literary figure very much like the then-widely respected, famously hard-drinking Ko. A recent Korea Times article provides a partial translation:

Never sit next to En. Poet K warned me of his bad habit of groping young women. I blame my fading memory as I sat next to him some time later. Me too. My silk blouse that I borrowed from my sister for the outing was creased. Years later I met him again at a year-end party thrown by a publishing company. He sat next to a married editor and as usual he was groping her. “You, the cranky old man!” I yelled at him and ran away…

The erasure of the once-beloved Ko’s legacy began almost immediately, starting with the Maninbo Library, a re-creation of his book-piled study that opened just last November in Seoul’s Metropolitan Library. Not only will the installation come out, his poems themselves will soon disappear from school textbooks, bringing to mind Spacey’s 11th-hour excision and replacement from All the Money in the World, Ridley Scott’s already-complete biographical drama about J. Paul Getty. “If I had been in the movie as it had stood and we hadn’t been allowed to reshoot,” said co-star Michelle Williams, “it would have felt tainted and something to be shy of – something to just forget about entirely. Because it’s upsetting to watch someone who has done these things, it’s upsetting to watch them glorified.”

“Her relief is plain,” writes David Bromwich, commenting on “the ethics of altering a work of art to accommodate a sudden change in the political weather” in the London Review of Books. “By co-operating with the erasure, Williams has been shriven of guilt by association with Spacey, a burden the movie as originally shot would have forced her to bear. An anthropologist looking at the mood exhibited here — and Williams is not alone — might take it to represent a culture a few months from descending into shamanism and sorcery.” Korean society has a long history of shamanism, and the practice still manifests in various forms today, but the Ko affair seems an illustration of the much more fearsome caprice of Korean public sentiment, the force that, among its other dramatic accomplishments, unseated former president Park Geun-hye.

It does say a great deal about how much this country has changed over the past 30 years that some sort of deep-state operation didn’t silence the accusations against Ko before they ever came to light. As a real contender for the Nobel, he could have brought official Korea much more of the international prestige it so openly craves. (I just last night had dinner with a television reporter, formerly of Korea’s global propaganda channel, who told of being forced to ask a Nobel-winning scientist with no evident connection to Korea why none of her countrymen had yet won the prize themselves.) But maybe, at the age of 84, his prospects don’t look quite like they used to.

The outcome of Ko’s situation so far differs sharply from that of Hong Sangsoo, the maker of formally experimental comedies sometimes called “the Woody Allen of Korea.” (Though I’ve occasionally said that as well, it probably makes more sense to compare him to the equally prolific but more stylistically similar Éric Rohmer.) He made headlines in 2016 when he left his wife of thirty years for actress Kim Min-hee, a move treated as scandalous at the time — not least because the story played out so much like that of a television drama — but which many in film circles here recognized as just the most serious in a string of affairs. But little has been said more recently about Hong and Kim’s professional and romantic relationship, both of which have endured as they continue to draw international acclaim with what remain, after all, Korean films. (Heaven help them both, though, if foreign critics turn on their work.)

Despite having watched Hong’s movies for years, and even considering them one of the main factors in the development of my own interest in Korea, I can’t gin up much interest in his moral transgressions. At times I wonder whether I’d want to enforce the “rules” of sexual morality on him, such as they exist, any more than the “rules” of cinema, which his films draw much of their effectiveness from breaking. That puts me on an (at the moment) deeply unfashionable side of the debate over the extent that the qualities of art can or should be considered independently of the qualities of the artist. But the fact remains that, in the West or in the East, we’ve long expected and even desired that our artists, and especially our successful and high-profile ones, inhabit a realm apart from the rest of us. We’ve had our reasons for that, and even if we’ve just changed our minds about it, we might take a moment to consider what those reasons were.

Some explanations given for the swift action taken against Ko Un and others during what the press has called “Korea’s #MeToo movement” cite the urgent importance of dismantling Korea’s “patriarchal” society (although one underestimates the influence always wielded by Korean womankind at one’s peril), but could it have just as much to do with fear? In a more recent New Yorker piece, Gessen quotes from the Cold War-era writings of feminist anthropologist Gayle Rubin: “To some, sexuality may seem to be an unimportant topic, a frivolous diversion from the more critical problems of poverty, war, disease, racism, famine, or nuclear annihilation. But it is precisely at times such as these, when we live with the possibility of unthinkable destruction, that people are likely to become dangerously crazy about sexuality.”

Now, Gessen writes, “we are living with the possibility of unthinkable destruction, but we seem to be spending significantly more time discussing the sexual misbehavior of a growing number of prominent men than talking about North Korea or climate change,” and in few nations does one hear the subject of North Korea seriously brought up less often than South Korea. The farther the time of a united Korean Peninsula falls out of living memory, the more public attention seems to turn outward, verging at times on an obsession with foreign judgment and resulting in the direct, undigested adoption of foreign ways as an attempt to satisfy it. This country made itself strong enough to get in that position, according to the economic history, through exports; there’s something disheartening in seeing it engage now in the wholesale import of moral fashions, however just the cause.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Anti-Trump Protests, Anti-Park Protests, and the Koreanization of American Politics

The Korean President’s Artist Blacklist, Product of an Insecure State

Korea Through the Eyes of Hong Sangsoo, the Éric Rohmer and/or Woody Allen of Korean Cinema

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.