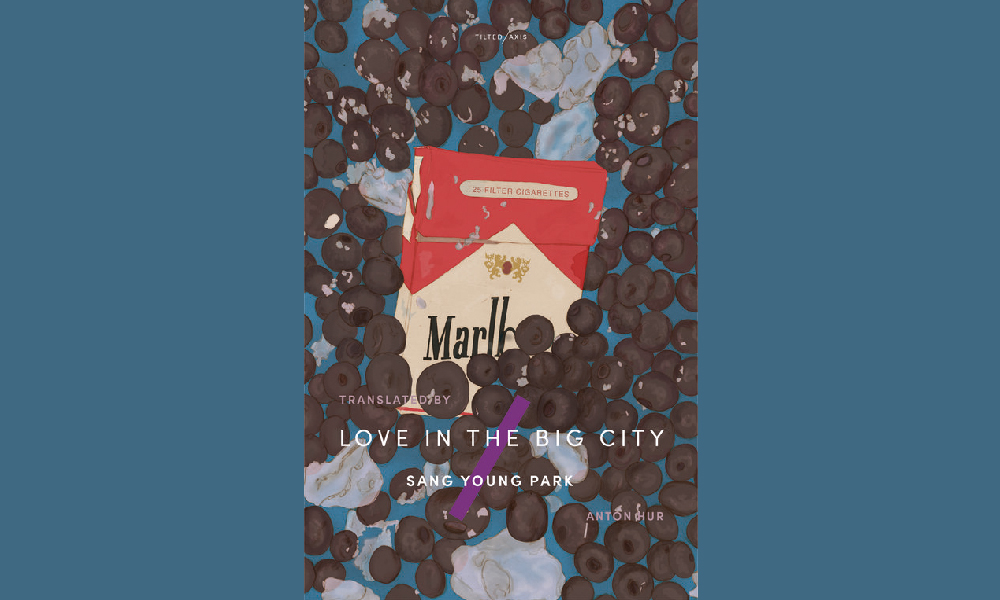

In recent years the internet has launched into the zeitgeist the term “incel,” referring to individuals filled with resentment about their state of involuntary celibacy — i.e., sexlessness. In nearly all cases the incel is a heterosexual male, though some have speculated on the nature of his homosexual equivalent: a tweet I saw a few months ago, for example, posited that “the gay version of ‘incel’ is not finding a long-term relationship.” If so, then the protagonist of Sang Young Park’s novel Love in the Big City is a kind of incel. With opportunities for casual sex perpetually close at hand, thanks not least to smartphone dating apps, Young longs for nothing more than a deep and lasting connection. Yet all the overlapping cultures that clam him — gay culture, “hook-up” culture, social-media culture, Korean culture — seem to have allied themselves against the fulfillment of that desire.

Matters aren’t helped by the company Young keeps. His best friend Jaehee, namesake of Love in the Big City‘s first section, acts as if given over to the pursuit of dissolution, compulsively smoking, drinking, and going to bed with any man who will have her. “Jaehee and I had very little sense of chastity, or none at all, to be honest,” Young tells us in his narration, “and we were apparently known for it in our respective spheres.” Having bonded over a shared penchant for the excesses in which impecunious twenty-somethings can indulge, he and Jaehee fall into a pattern of mutual support, and more so mutual reinforcement. When Jaehee falls pregnant, with predictable uncertainty as to the father’s identity, it is Young who accompanies her to the clinic in hopes of an abortion — and apologizes for the outburst of anger she releases on its moralizing doctor.

Despite sounding more troubled than not in his telling, Young’s time with Jaehee, which even includes a period of cohabitation, comes to look in retrospect like an idyll. When Young goes off to perform his mandatory military service, Jaehee goes off to study abroad in Australia, a choice that appears to plant in her mind the seed of reformation. Park has a knack for this sort of ironically telling detail: such is the disorder of Jaehee’s life that a stint in Australia, of all places, sets her on the straight and narrow. Or at least it sets her on a path just straight and narrow enough to lead to the altar: Park opens the novel with a scene at her wedding, and in it Young fields questions about his weight gain and inchoate writing career from their old French-literature department classmates at the “mid-tier university” from which they graduated.

Young may be a homosexual French-literature major, but in a victory for minority representation, he doesn’t exhibit a particularly strong instinct for beauty. Far from TV-drama Gangnam glamor, his is a dingy world familiar to readers of the kind of recent novels that regard the stifled lives of downwardly mobile Seoulites in their twenties and even thirties. Their clothing is cheap. Their food is cheap (and usually accompanied by great quantities of even cheaper drink). Their apartments are cheap, barely outfitted rooms in aging buildings, yet also burdensomely expensive. Jobs are temporary, and in any case unpromising; evenings not spent in front of the television wearing mask packs are spent at clubs that depress even with the lights down. Young takes an unsparing view of all this, as he does of his own hairy heaviness; his acknowledgment of Jaehee’s also-lackluster appearance implies a compensatory side to their sexual recklessness.

Whatever their motivations, they can have little to do with pleasure per se: in Park’s rendering, Young and Jaehee’s behavior comes to look like an anhedonic oscillation between repression of and capitulation to their own impulses. Jahee’s exit from this cycle by settling down with an implausibly stable-seeming man comes to Young as a shock (“It was more likely that I would take a bride than she a groom”), though Park allows little confidence in her marriage’s long-term prospects. We never do find out how she fares in sustained monogamy, since her wedding day evidently marks the end of her and Young’s friendship. Jaehee isn’t the only person suddenly to vanish from his life: men, too, come and go with little notice, leaving Young the up-and-coming novelist to write versions of the relationships he had with them, and thus to claim ownership over the vicissitudes of his life.

Young recounts his involvement with a series of men including an engineering student whose love is reserved primarily for his own unremarkable compact car. “We both had low self-esteem, regularly felt suicidal compulsions, were bullied as kids, and pretentiously enjoyed arty films and books while hating basic crap like Haruki Murakami, Hong Sangsoo, French literature, and Audis.” Their relationship continues “until it became boring and I stopped returning his messages”; Young later learns that he’s been in a wreck, dying in his beloved Kia. A much more intense liaison forms with a man encountered in a continuing-education philosophy class (whose syllabus includes Spinoza’s Ethics and Barthes’ A Lover’s Discourse). Referred to only as hyung, a Korean term with which a younger man addresses an older one, he turns out to have a dozen years on Young — and, worse, to speak like “a stuffy, middle-aged ajussi.”

As rendered in English by Anton Hur, Love in the Big City never breaks the narrative to explain what an ajussi is, or for that matter what a hyung is, and should thus become a model for future translations of Korean literature. Extremely common in Korean life, these words and others like them — Umma, sunbae — lose their feeling when presented as exotic linguistic dressing or objects of scholarly explication. Park wrote this novel in Korean for a readership that knows exactly what things like hagwon and Kongsuni dolls are, a perspective best retained in translation. Hur trusts the reader of Korean literature in English to look up unknown references, to infer their nature from context, or at least to pass over them without distress. And at this point, is it so unrealistic to assume on the part of such a reader a basic familiarity with Korean culture?

Even those barely acquainted with modern Korea will feel a certain sense of recognition at the character of Young’s mother. “Our family is extremely ordinary, and like any ordinary patriarch, my father had so many affairs that my mother eventually divorced him,” as Young puts it. The split initiated her transformation into a now-archetypal figure: the self-made, or rather self-remade, middle-aged Korean woman who leans heavily on the Bible. Having become a freelance matchmaker, she found success “when men and women from the affluent Gangnam and Songpa districts, who had almost ended up forever single after the upheavals of the Asian financial crisis of the late nineties, began turning their attention to the idea of marriage.” It was then, Young recalls, that she believed “that if our family put its best foot forward, we could end up in society’s top percentile and live the dream of a beautiful Scandinavian lifestyle.”

Things didn’t turn out as planned. Stricken by cancer, Young’s mother finds herself cared for by the son whose whose writing she claims never to have read. With her own exit from his life imminent, Young gets it in his head to introduce her to his “hyung” from philosophy class; a disaster is perhaps averted when he fails to show up at the appointed hour. This isn’t as a surprise: the man comes off as posturing yet furtive, in thrall to his past in bombastic left-wing campus activism and desperate to conceal his homosexuality. To an extent, Park depicts him as simply a product of a chronologically proximate yet culturally distant generation, some of whose members use phases like “the American Empire” without irony and take someone of Young’s age to task for listening to American music. Young’s reply: “What kind of a gay man isn’t into Britney or Beyoncé?”

Yet when Young later refers to himself, with characteristic sarcasm, as a “decadent by-product of American imperialism and Western capitalism,” it feels as if some of these arrows have stuck. Proficient in English, this avowed hater of “basic crap” admits to having developed that proficiency by watching “episodes of Friends, Will and Grace, and Sex and the City on repeat.” This in contrast to Gyu-ho, the more age-appropriate boyfriend with whom he takes up after the hyung, who “was surprisingly bad at English but was great at East Asian languages like Mandarin or Japanese.” A recent arrival in Seoul (or rather the more-or-less nearby city of Incheon) from Jeju Island, Gyu-ho exudes rustic earnestness and charm. This contrasts with, or rather complements, Young’s chosen persona of the jaded and sardonic urbanite. In due time after their chance meeting at a club, the two become lovers.

Or rather they become lovers after their third date, according to Gyu-ho’s personal rule about when to sleep with a man. Developing such a system in the first place would seem to imply a fairly active sex life, but it nevertheless strikes Young as impossibly quaint. The relationship that follows has rough patches, and seemingly severe ones: “Twice we even split up,” says Young. “We saw different people. A lot of people in my case, and probably the same for Gyu-ho.” Still, it delivers him into a kind of domestic bliss; the two even merge their lives to the degree that they study Chinese together and both arrange transfers at their respective workplaces to Shanghai. But that step is thwarted when Young learns he’ll need to undergo a physical, complete with blood work that will reveal the HIV infection he’d picked up from an even more promiscuous earlier boyfriend.

Gyu-ho moves to China, leaving Young to drift back into the open socio-sexual sea. There he finds a middle-aged Malaysian businessman in whose Bangkok hotel room (coincidentally, the same one in which he’d stayed with Gyu-ho on an earlier vacation) he spends days at a stretch. “Lying there on my Tempur bed, I came to the realization, Wow, this really is a very plush and perfect state of death, even boredom can get boring,” he says. This prompts “some half-hearted swiping on Tinder. Anyone would do, anyone to get me out of that coffin of a bed and into the world outside, from the rotting cesspool of my life to what lay beyond.” The effort yields little, and Young’s narration continues to transmit general disorientation and desensitization. If he feels out of place in the world — hardly uncommon among fiction writers — the cause may run deeper than sexuality.

Young’s aesthetic sensitivity manifests only in response to all-consuming desire. “Had the streetlamps and neon signs always been this spectacularly bright?” he asks himself on one such occasion. “Why was Seoul so beautiful all of a sudden?” It’s reminiscent of what impresses him in his resented mother: “A passion for loving Jesus, for throwing oneself wholly into the act of living. That was, perhaps, the feeling I had toward my guy at one time, a feeling of giving myself up to something.” But Young belongs to a generation for whom religious ecstasy is in short supply, meagerly compensated for by an ever-growing variety of algorithm-aided satisfactions. A couple years ago I even noticed ads in the Seoul subway announcing the local launch of no less a manifestation of the “American Empire” than Tinder. “A new way to discover friends,” announced the posters. That’s certainly one way of putting it.

Related Korea Blog posts:

The Great Korean Plastic Surgery Novel: Frances Cha’s If I Had Your Face

Six Expatriate Writers Give Six Views of Seoul in a New Short-Fiction Anthology, A City of Han

Los Angeles and Seoul, a Tale of Two Ugly Cities

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: A Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.