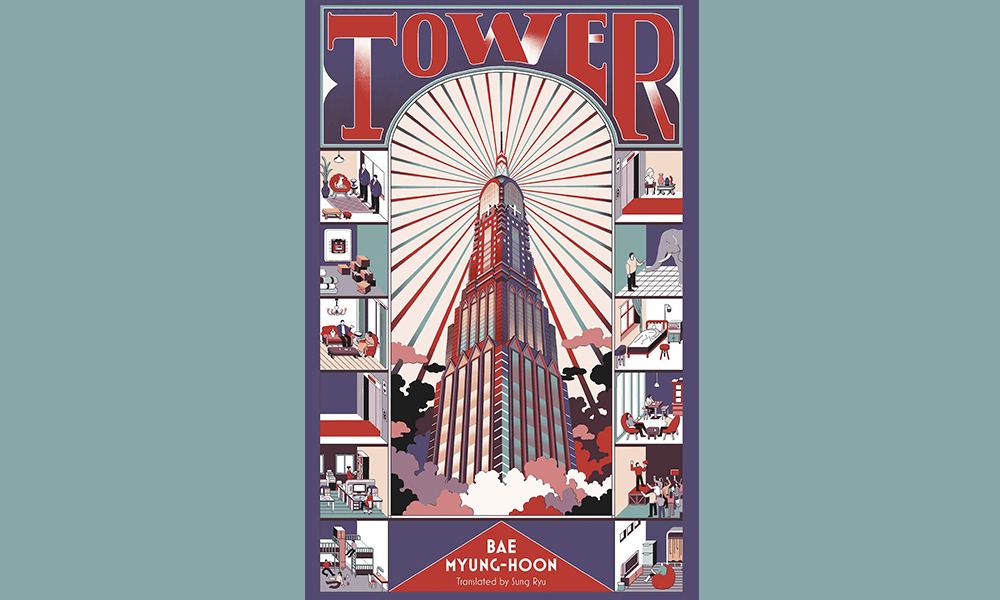

Bae Myung-hoon’s Tower (타워) comprises six interlinked stories, which take place almost entirely within a single building inhabited by 500,000 people. To that setting I imagine Western readers reacting with the look of the stunned distaste I sometimes receive when, back in the United States, I describe the standard form of middle-class housing in Seoul: clusters of 10, 20, 30 buildings, rising to 20, 30, 40 stories each. That verticality alone signals dystopia to many Americans, but to no few English as well — most notably J.G. Ballard, whose 1975 novel High-Rise dramatizes the swift and total breakdown of society that occurs in, and is seemingly caused by, a luxury apartment complex of the titular form. No such fate befalls Beanstalk, the 674-story tower imagined by Bae, though it does experience a few close calls, subject as it seemingly is to constant threat from within and without.

Beanstalk isn’t just a building but a sovereign nation unto itself, locked in an ongoing Oceania-and-Eastasia-style geopolitical conflict with the distant country of Cosmomafia. This perhaps reflects the interests of the Seoul National University international-relations scholar Bae was when he began to build a readership as a writer of fiction. But in just over 250 pages, he also describes or alludes to aspects of Beanstalk and life within it in a range wide enough to reflect active fascinations with structural engineering, urban development, terrorism and antiterrorism, geographic information systems, literature, military strategy, Machiavellian politics, and Buddhism. The state of nirvana is invoked several times, once as a fighter pilot downed in a vast desert feels death’s approach (little knowing that the Beanstalkians have banded together to comb through satellite photos, facilitating his rescue), and again when an Indian elephant plunges from a 321st-story window.

The elephant is called Amitabh, a name borrowed (as Bae revealed in a recent podcast appearance) from Bollywood superstar Amitabh Bachchan. Show business bears more directly on the life a celebrity dog known as Film Actor P, another of Tower‘s non-human characters, who not only figures into several of its stories but turns up again in the last of its appendices to give an “interview.” You may at this point suspect the book of an unconventional structure, either by the standards of novels or those of short-story collections. Nor is it formally homogenous, with one epistolary story breaking up the omniscient third-person voice and two of the appendices constituting excerpts of texts referred to in the foregoing narratives: a sociological study of one of Beanstalk’s floors and a myth-like tale of a polar bear (who eventually does manage to attain nirvana) ostensibly by “Writer K,” star of the second story.

Writer K once accepted a bribe that provided him with not just a house in Málaga but a house in Málaga and a robot through which to survey the property remotely from Beanstalk. We thus know that Beanstalk isn’t in Spain, though where in the world it does stand Bae never makes explicit. That the pilot crashes in China’s Taklamakan Desert suggests east Asia, and many elements of Tower‘s stories invite comparisons to Bae’s homeland of South Korea. Here the sort of politico-cultural palm-greasing in which K gets involved is barely concealed, and the kind of disengaged nature-appreciation he cranks out when the political heat turns up constitutes a time-honored literary tradition. Amitabh is brought into Beanstalk as a unit of its riot police, in an effort to contain increasingly forceful protests in front of city hall — the like of which I witnessed not long after coming to Seoul.

As in Seoul, some of Beanstalk’s unrest erupts in response to large-scale redevelopment: here neighborhoods have been emptied out and scraped away to make room for the aforementioned high-rise apartment complexes, whereas in Beanstalk it happens to floors or sections of floors. Beanstalk’s countless elevators are subject to the same kind of controversies that attend the operation, maintenance, and extension of the Seoul Metro, and the building’s spatial nature has also given rise its to its own abstract and tendentious ideological labels: the “verticalists” prioritize the machinery and capital needed to move people and things from one floor to another, while the “horizontalists” prioritize the labor and muscle needed to traverse the floors themselves. The former seem more represented on the affluent, more recently built upper floors, while the latter tend to occupy the humbler, older ones below — a somewhat predictable objective correlative of having and having not.

However high or low their status within the structure, all Beanstalkians appear to be better off than the people of the poorer unnamed country that surrounds them. After more than six decades into their building-turned-country’s existence, some have developed “terraphobia,” a fear and loathing of descending to the first floor, let alone stepping outside. (This condition strikes me as opposite to that which afflicts a writer friend of mine in Los Angeles, who eschews high-rise life because “humans were meant to live on the ground.”) Whether they hail from Beanstalk or the land that enclaves it, most of Tower‘s characters have Korean-sounding names: Professor Jung, Doctor Song, Kim Minso, Choi Sinhak. Does this mountainous building stand, then, for greater Seoul, which with half the population of South Korea (as well as most of its important institutions) often does indeed feel like a city-state within the country?

Bae includes one human character from farther afield: Şehriban. a Muslim (and given her name, presumably Turkish) agent of Cosmomafia resident in Beanstalk under the professional cover of working as an interpreter. Despite having warmed to the Beanstalkians in her years among them, she doesn’t hesitate to carry out the Cosmomafian orders she receives one day: purchase a series of properties within the building pre-rigged with bombs during its construction, and prime those bombs to detonate at the appointed hour. The passages on Şehriban’s background and motivations read as if somehow hollowed out on the way to the book’s English version, which does at least include the self-justifying sentiments of her predecessors in this elaborate long-term operation: “Watching Beanstalk add floor after floor, they had naturally associated it with the tower of Babel. Look how massive it is. It’s got human vanity written all over it. It’ll be another Babel.”

As with the movie-star dog, references to Babel arise throughout the book. But is the apter comparison between Beanstalk’s condition and the immoral disunion that befalls the city of the Bible (Bae has described himself as a Christian, his narrative use of Buddhism notwithstanding), or between Beanstalk’s construction and that of the Tower of Babel, whose heavenward rise causes humanity so much trouble? The punishment of hubris has in any case proven a reliable theme for Korean stories, from novels to major motion pictures: take by Kim Ji-hoon’s The Tower (also originally 타워), a visual effects-laden Korean update of The Towering Inferno set in a fictional 120-story complex on the Han River. That building’s conflagration is set off when a helicopter crashes into it in a windstorm, having been hired to sprinkle snow outside the windows for the delight of rich tenants gathered at an exclusive Christmas party.

Certain of Bae’s characters, too, sense the most severe threat in wealth and the isolation it encourages. An Intelligence Bureau officer believes that, whatever Cosmomafia gets up to with its bombs, “Beanstalk was already under attack, an attack mounted by those who did not see Beanstalk as a place where people lived but simply as a real estate market” — a demographic as powerful as it is insatiable, one whose demands have visited developmental grotesqueries (resulting in the occasional genuine disaster) on Seoul and other world capitals. On a smaller scale, one appendix, an “excerpt from the introduction to A Study on Level 520,” illustrates the processes by which a neighborhood loses its informal social institutions, in this case a coffee shop, and thus ceases to be a neighborhood at all: “In just one year we had gone from being people of Level 520 to people of Beanstalk.”

Whatever such depredations affect the life of Seoul’s neighborhoods, they’ve had more than a decade to worsen since the book first came out. Originally published in 2009, it appeared in a new edition just last year, reaching the much larger readership Bae had cultivated in the meantime by prolifically mounting his own satirical social, political, and economic critiques within the parameters of science fiction. That genre hasn’t been abundantly served by Korean literature, much less by Korean literature in translation (though the effort on this book from translator Sung Ryu and British press Honford Star may begin to change that). For this relative dearth I’ve often heard the same explanation given: South Koreans hardly need stories of high-tech dystopias when they already live in a real one. That reason may not be entirely plausible, but then neither is Beanstalk, and Tower certainly doesn’t suffer for it.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Living the Vertical Life in Seoul

Blade Runner 2049 and Los Angeles’ Korean Future

Could Seoul Be the Next Great Cyberpunk City?

An Ajeossi and His Robot (or, How Korean Film Dramatizes Disaster)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.