Over the past few weeks I’ve plunged into addiction: an addiction to Duolingo, the language-learning app that has claimed more than a few formerly normal lives since it launched for the public seven years ago. Or perhaps the word “normal” is excessive, given that the population most susceptible to Duolingo addiction distinguishes itself precisely by a willingness to stare at a screen and grind through foreign-language quizzes for hours at a time. Sensing, perhaps, the fate that could befall my already shaky time-management system, I avoided looking up or learning anything about Duolingo when first I heard of it. My Korean teacher brought it back to my attention a year or two ago, when he started using it out of a “Despacito”-stoked interest in acquiring a little Spanish. He mentioned to me that the app had recently added a Korean-language course, suggesting I give it a try and let him know my opinion on its effectiveness.

Even without the assistance of Luis Fonsi and Daddy Yankee, Spanish would still be the most popular language among English-speaking Duolingo users. Of the 23,400,000 English-speakers studying the language of Cervantes through the app, I wonder how many are my fellow Americans trying to ameliorate their embarrassment about their lack of functionality even after enduring five to ten years of compulsory Spanish classes in school. In second place after Spanish (albeit with about ten million fewer learners) comes that alternative bane of the Anglophone schoolchild’s existence, French. Despite the French language’s much-bemoaned loss of status and claim to universality over the past century, becoming francophone nevertheless remains an aspiration for many of us, not least, as I wrote about in a LARB essay last year, because of the high regard in which the French hold their language, and the high standard of its use to which they hold themselves.

The broad interest in learning Spanish and French, as well as the long history of teaching both languages in English, makes for fairly extensive Duolingo courses. French breaks down into eight tiers, each containing between 10 and 25 subject areas, from “greetings” and “family” to “technology” and “money” to “artistry” and “spiritual.” (Spanish has only one tier fewer.) Each of those subject areas consists of five levels of quizzes, most of which involve translating words or sentences from French into English or vice versa, with occasional listening and pronunciation tests. The reliance on English as a reference language does give me pause, a pause in which I think back to William Alexander’s Flirting with French, one of the French-learning memoirs I read for the aforementioned essay. In it Alexander, engaged in the project of picking up French again in middle age, relays a piece of wisdom offered to him by a teacher who refuses to use English in class:

French is not a translation of English, he says. It is not English that has been coded into French and needs to be back-coded into English to be understood. French is French. When French people say something in French, it is not that they really mean something in English; no, they mean something in French. You cannot simply replace a French word with an English word. To understand what a French word means, you have to understand les circonstances in which it is used.

But on this point Alexander himself exhibits a self-defeating stubbornness: “When I want to say something in French, I think of what I want to say in English and then convert that into French,” he writes, despite knowing that “you must remove the mental middleman of translation, for your brain cannot translate back and forth fast enough to keep up with a conversation.” This goes even more so for languages with little or no relationship to English: Mandarin Chinese and Japanese, for example, both of whose Duolingo courses I’ve also been working through, both of which take essentially the same form as the ones for French and Spanish. The Japanese course is about as long as the Spanish one, but it doesn’t test your pronunciation (though pronunciation is admittedly of less critical importance in Japanese than it is, as I’m now finding out through my own many small failures, in a tonal language like Chinese).

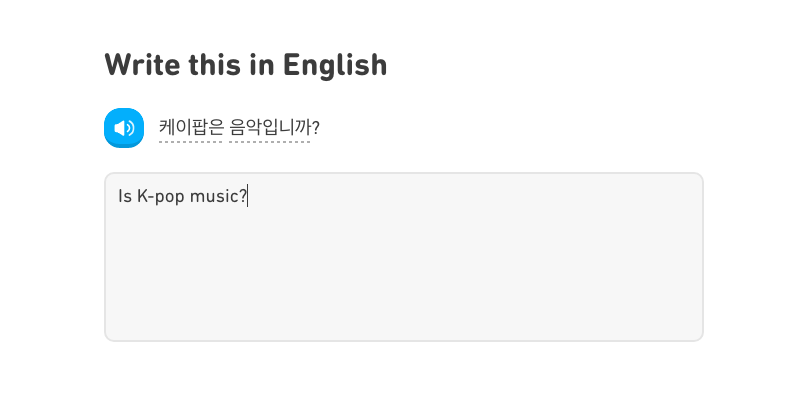

And then we have Korean, the shortest Duolingo course among all of these, as well as the least full-featured. Some of this thinness must owe to the comparative recency of its introduction, an introduction surely hastened by pressure from rapidly multiplying K-pop and K-drama fans the world over. (Those of us who have little time for those most visible aspects of modern Korean culture can rest assured that the course saves “pop” for its very last subject area.) The fact also remains that Korean isn’t anywhere near as pedagogically developed a language as Chinese or Japanese, let alone French or Spanish: even students who come to the best-known university language programs in Korea today complain of illogical structures and inefficient methods. The Korean language demands an enterprising student, one willing to seek out as many avenues of learning as possible and use them to approach the material from every angle: it was true when I started learning Korean by myself more than a dozen years ago, and it still seems true today.

But the tools available to the solo Korean-learner have come a long way in that time, as the very existence of Duolingo’s Korean course makes clear. Still, working through the lower levels of its Korean course to get a sense of its approach to the language, I was faintly reminded of the simple Flash quizzes with which I originally learned hangul, the Korean alphabet, in free moments during my job as an evening announcer at a radio station. This was a time before smartphones, but also before Youtube; podcasts technically existed, but few of them taught languages and none of them taught Korean. From there I moved on to what Korean grammar textbooks I could pull out of the local university library, none of them published after about 1987. Nowadays, someone interested in learning the Korean language — and more and more, anyone interested in learning anything — needs only make a couple of web searches to be overwhelmed by educational content in every textual, audio, and visual form, most of it completely free.

The past decade has also seen the emergence of the kind of partially free apps and services, language-related or otherwise, for which the neologism “freemium” was invented: the basic experience comes at no cost, but it constantly makes you aware of an ever-expanding suite of extras available for purchase. Cellphone-based freemium games now constitute an industry unto themselves, especially here in Korea, and on the mechanical level Duolingo is a freemium game like any other. Performing variations on the same tasks over and over again, the player completes levels, sees their rank rise or fall against those of other players, and even earns in-game currency and “experience points,” a term I remember from my own gaming days in the 1990s. With each mistake, each word or sentence mistranslated, the player loses one “heart” — of which a paid premium membership will infinitely extend their supply.

This is what Silicon Valley calls “gamification,” the application of principles from video games to non-gaming contexts. (All of us have, at one time or another, felt and rued the effectiveness of gamification as implemented in social media.) In my schooldays, nothing could have seemed to me farther from playing video games than sitting through Spanish class — in fact, I spent most of my time in the latter fantasizing about the former — and I assume the kids taking French felt just the same. But how many of the subjects studied in school come so well suited to the nature of practice and progress as video games conceive of it, as well as the immediate feedback they provide? (Indeed, Duolingo has also introduced a version of its product specifically for schools.) Only after graduating college did I overcome my aversion to the study of foreign languages, and soon thereafter I came to know the modest joy of what I privately considered “leveling up” in Korean, a process Duolingo makes explicit.

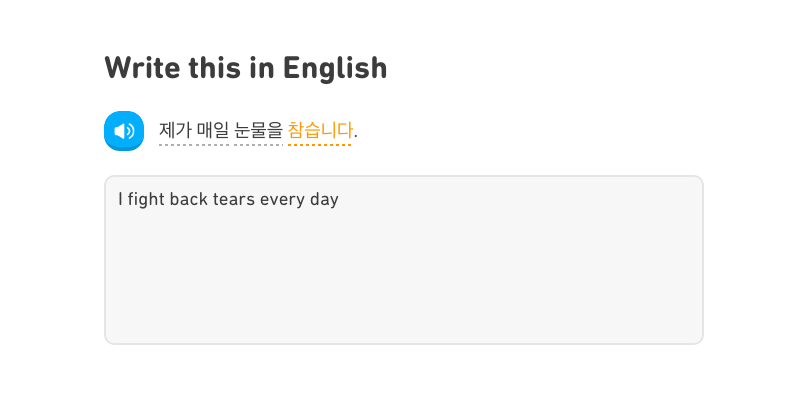

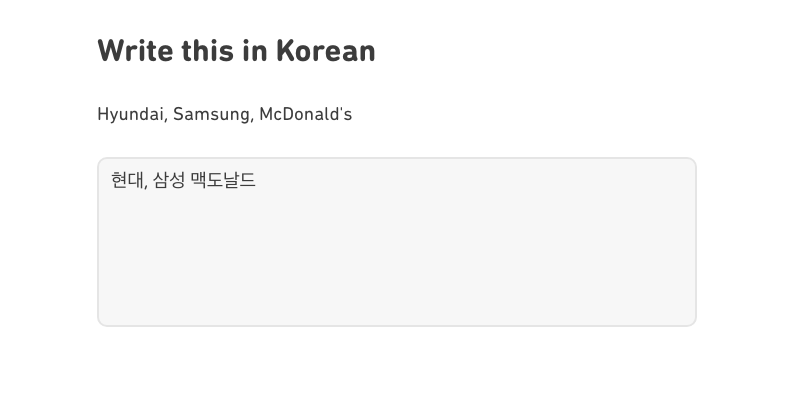

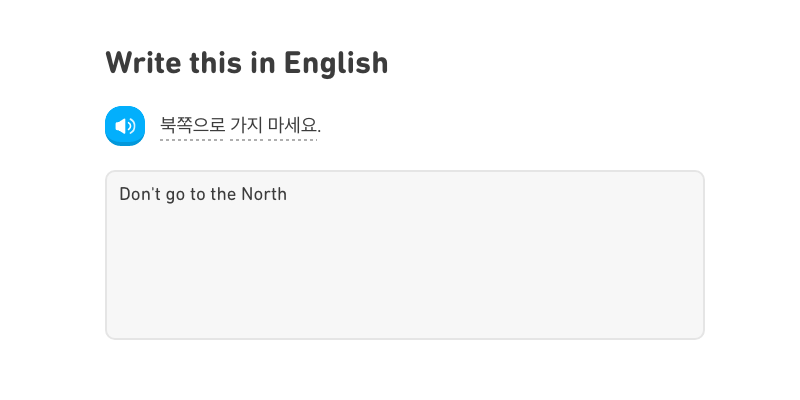

Unlike a classroom, Duolingo automatically and continuously calibrates the difficulty level to the individual learner’s skill level, always tending toward the kind of not-too-easy, not-too-hard challenge likely to induce what Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi branded the “flow” state. It also teaches without teaching, exactly: a Duolingo user may spend days or even months playing before they realize that the app has never once asked them to memorize anything, nor even to simply read, listen, or absorb. From the moment a novice Korean learner, even one with no knowledge of hangul, begins Duolingo’s Korean course, they’re answering questions: first multiple-choice questions with only one choice, then with one obvious correct answer, then variations on questions previously answered. By the time the sentences become genuinely difficult to translate, the gamification has done its work: whether the player still wants to learn Korean or not, they will very much want to keep leveling up, and to precisely the same degree students don’t want to do their homework at that.

In a popular TED Talk, communication skills trainer Marianna Pascal recommends that English-learners “speak it like you’re playing a video game.” Someone speaking English as if were a video game he’s still learning “doesn’t feel judged. He is entirely focused on the person that he’s speaking to and the result he wants to get. He’s got no self-awareness, no thoughts about his own mistakes.” Pascal underscores the difference is between a speaker “who’s got a high level, but totally focused on herself and getting it right, and therefore, very ineffective” and a speaker at who’s “low-level, totally focused on the person she’s talking to and getting a result.” The perfect is the enemy of the good, to coin a phrase, and learners of English — the most popular language on Duolingo, incidentally — forget it at their peril. Alas, schools instill the opposite message: “English is not really being taught like it’s a tool to play with,” Pascal says. “It’s still being taught like it’s an art to master. And students are judged more on correctness than on clarity.” And what goes for English goes for other languages as well.

Despite the overall soundness of her points, Pascal uses the closing lines of her talk to reiterate a troubling premise: “English today is not an art to be mastered, it’s just a tool to use to get a result.” This is the attitude that propagates “Globish,” the utilitarian, deracinated, and indeed debased version of English with which I previously dealt in another LARB essay. To take a wholly results-oriented approach when first learning a language is good sense, but to discard the concept of mastery out of hand, demoting a cultural work as vast as a language to the status of a mere tool, floods the act of language-learning with nihilism. “Good enough” is ultimately not good enough, neither for life nor for one’s own motivation. I’ve often been frustrated by the Korean language, but even before I moved to Korea, and before the emergence of such fiendishly encouraging study aids as Duolingo, I was never frustrated enough to consider quitting. What kept me going wasn’t the fact that I could use Korean to get people to do more or less what I wanted, but the impossibly distant vision of linguistic mastery.

Can you master Korean with Duolingo? The many Westerners here who’ve never quite got their Korean functional may be disappointed, but not surprised, to hear that you can’t. But you can, through translating and retranslating the thousands sentences Duolingo throws at you — often bizarre sentences, but impressively, never ungrammatical ones — imprint the structure of the language on your brain deeply enough to at least make mastery conceivable. (The sooner Duolingo implements listening and pronunciation tests of the kind used in its Spanish, French, and Chinese courses, the better: simply hearing the words spoken to you is one of the most difficult aspects of Korean for a foreigner, and most of us can only hear correctly what we’re able to say correctly.) The question, then, is what best to supplement Duolingo with: more than a decade into my own study of Korean and nearly four years into my life in Seoul, I myself still take one-on-one lessons and maximize the amount of Korean radio, podcasts, films, television shows, and books I consume on a daily basis.

Korean-learners tend to underestimate by an order of magnitude how much linguistic input the task requires, on the apparent assumption that following the rules of the language can take them farther than it actually can. But the “rules” of the Korean, much more flexible than those of languages like French or German (Duolingo’s fifth-most popular course, seven spots above Korean), are more effectively internalized through inference than explanation, and in that sense Korean is well suited to a no-explanation, all-example system like Duolingo’s. Over time I’ve assembled a standard list of Korean-learning strategies I recommend to everyone who asks, and it only took a few hours’ experience with Duolingo to confidently add it. Duolingo hasn’t replace any of the strategies already on the list, nor, certanly, will it be the last one I add, and even maxing out your score on every one of its challenges won’t get you ready to go on Our Language Battle. But you’ll certainly be spending your time more productively than most everyone else staring at their screens on the Seoul subway.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Talk Like a Busanian: How to Master the Ever-Trendier Dialect of Korea’s Brash Second City

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.