“I’ve been to China and I’ve been to Japan,” says Rana Mitter at the beginning of his BBC Radio 3 documentary South Korea: The Silent Cultural Superpower, “but I’ve never got off at this place before.” Increasingly many Asia-savvy global travelers have uttered variations on that line in the past decade, having known, of course, of this country’s existence and even of its history, but never having regarded the actual experience of it as a priority. Why has that changed?

The BBC has clearly taken an interest in the question, having sent potter Roger Law here at the end of last year for the five-part series Art and Seoul, and now having had Mitter come and take a closer look at why so many of us know something about Korean culture today while so many of us knew almost nothing about it yesterday. When I interviewed Michael Breen, author of the respected book The Koreans: Who They Are, What They Want, Where Their Future Lies, he mentioned that, when he wrote its first edition in the 1990s, only when a friend pointed it out did he realize that he hadn’t said a word in the text about the products of Korean culture, and at that time didn’t feel he needed to. Now almost every major piece of writing about South Korea begins with them.

The Silent Cultural Superpower looks for the sources of modern Korean culture in many of the stops in Seoul that, if you follow Korea’s presence in the international media, you’ll expect: the tourist-thronged shopping streets of Myeongdong; the hip cafés of the historically countercultural Hongdae district; the sidewalk across from the Japanese embassy where protesters express their views on the “comfort women” issue in no uncertain terms; Zaha Hadid’s Dongdaemun Design Plaza (a “huge, sinuous, gorgeous egg of a building” as well as a “statement about what Korea is now”); and the foot of Lotte Tower, the under-construction symbol of the power of those giant corporations, a lineup also including such now globally known names as Hyundai, Samsung, and LG, that have “powered this country’s economic miracle and sent it global.”

Refreshingly, Mitter never sets foot inside a cram school or plastic surgery clinic, avoiding some of the topics all too frequently obsessed over in mainstream Korea coverage in favor of others not so commonly discussed. An examination of recent Korean film and television highlights the centrality of “the powerlessness of the Koreans,” as against the power of China or Japan or America or anywhere else, as a theme. It surfaced with special clarity in Ode to My Father (국제시장), Yoon Je-kyoon’s blockbuster from the Christmas before last. While it drew many comparisons to Forrest Gump, not without cause, the film’s story of one Korean man’s life from the division of his family at the end of the Korean War to his work abroad as a soldier in Vietnam and a coal miner in Germany to his struggles with redevelopment as a merchant in modern-day Busan tells a great deal of Korean history in domestically tear-jerking microcosm.

Ode to My Father has its inaccuracies, the product of artistic license as well as glossings-over, but in that sense it offers a valuable look at a certain kind of Korean perception of Korean history. In his review and analysis of the movie, Matt VanVolkenburg at Gusts of Popular Feeling breaks this down for the non-Koreanist, framing the film as “a national coming of age story” set in a harsh, unforgiving world in which “a weak Korea, beset by poverty and war,” a “shrimp among whales” ever caught between powerful neighbors, must struggle simply to exist. Hence, in this storytelling tradition, the tendency to portray Koreans as “blamelessly going about their lives when suddenly history crashes into them and sweeps them off their feet” (literally, in the case of Yoon’s previous tidal-wave disaster picture).

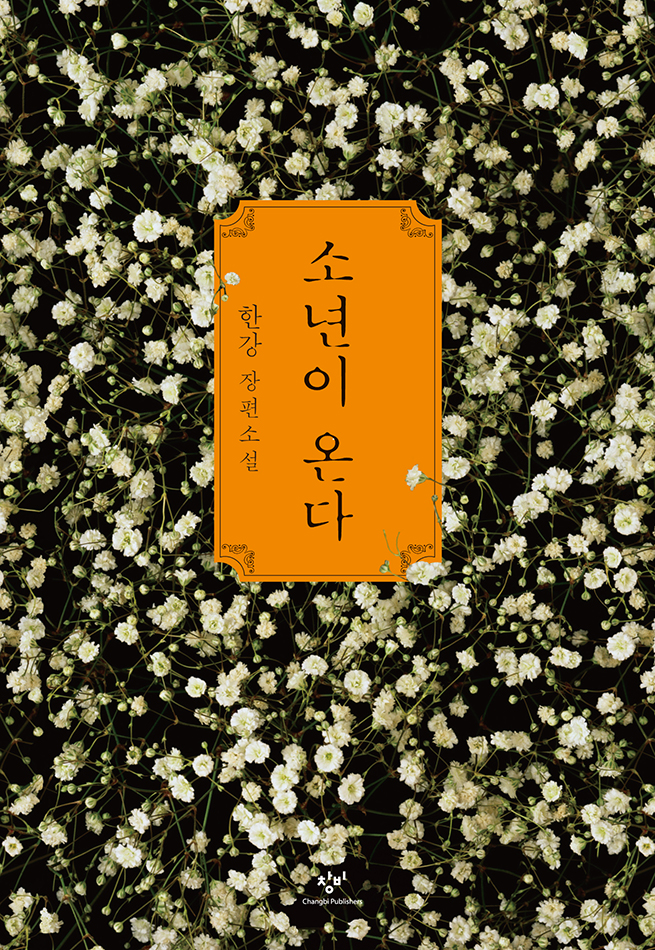

In The Silent Cultural Superpower we also hear from Han Kang, a novelist who’s broken into the English language in a big way with The Vegetarian (채식주의자), published in translation in the United States this month, and Human Acts (소년이 온다), just recently out in Britain. In the latter book, Kang takes on the theme of the powerlessness of Koreans from another angle: not their powerlessness against the whims of other, bigger countries, but their powerlessness against the whims of their own dictators. The program discusses on Park Chung-hee, the architect of South Korea’s industrial development who held the reins of power from 1961 until his assassination by his own security chief in 1979, but says less about his successor Chun Doo-hwan, who in 1980 ordered the military’s massacre of protesters which Human Acts takes, unblinkingly, as its subject.

Even the documentary’s inevitable coverage of K-pop takes a different tack. We hear one argument that the music “isn’t really Korean,” but a simple repurposing of Western pop forms, and we hear about its strategic use to improve Korea’s often troubled relationship with Japan, as in K-pop star BoA’s recording of songs in Japanese as well as in Korean. We also hear about its strategic use to retaliate against North Korea’s recent announcements of a hydrogen bomb test by setting up giant speakers blasting K-pop over the border, which the North reportedly fears might actually influence the minds of its young soldiers. (Silent cultural superpower, indeed.)

That grumpy neighbor aside, the much-publicized “Korean Wave” of culture, driven by music and television, has indeed swept to an impressive extent across Asia. When Mitter hits Myeongdong, he starts looking for Chinese people — no tall order, since these days that area seems populated by nothing but — to ask about their own degree of enthusiasm for K-pop. When he immediately finds some, he busts out fluent Mandarin to talk to them, which might comes as a surprise until you learn that he holds a professorship of the history and politics of modern China at Oxford’s Institute for Chinese Studies. It places him well to analyze Korea’s still-shaky relationship, despite all the Myeongdong-going girls who profess their love for the Chinese-Korean boy-band EXO, with the Middle Kingdom, summed up neatly by one of his Korean interviewees: “We still have a lot of wary eyes toward China.”

But in the West, the Korean Wave hasn’t done much more than splash against the shores. “I wonder,” theorizes Mitter, “if that’s because most K-pop acts reflect a regimented culture of centralized corporations and social conformism,” which leads into a talk about PSY’s “Gangnam Style” (as if I needed to provide the link for anyone who hasn’t yet seen its 2.5 billion times-watched video) and how the success of the track’s Seoul-specific satire and the goofiness of the rapping jokester doing it astonished everyone who assumed a highly groomed boy- or girl-band held the natural right to break the coveted American market.

This leads Mitter to look for the exact opposite of K-pop culture, deep in Seoul’s experimental music scene. He talks with Hong Chulki, a political theory graduate student by day and experimental musician by night who uses a laptop, mixers, various pieces of broken equipment, feedback noise, and the sound of air blown onto turntable needles to craft listening experiences meant to cleanse his head of K-pop, so unavoidably has it become woven into the sonic fabric of the city. This sort of thing also offers a catharsis, for Chulki and his colleagues, from a life in modern Korea dominated by social pressures, hated (though painfully competitive) jobs, and an older generation out of touch with and unwilling to cede any power to the younger one.

Comic artist Yoon Tae-ho dramatized these circumstances in his series Misaeng (미생), or “Incomplete Life,” which, adapted into a drama, became a surprise hit on Korean cable in 2014. Clearly the material works, even if it presents a side of Korea the country’s boosters would rather downplay. Those in the business of promoting Korean culture abroad understand that the now-characteristic high-gloss professionalism of so much of the country’s music, film, and television — and even, in some cases, comics and literature — appeals to the rest of the world. But they may understand it too much, ignoring the fact that the polish is only as interesting as the sorrow, humor, confusion, strangeness, and discontent with which it contrasts. Indeed, “the roughness at the edges,” Mitter concludes at the end of his short visit, “might be Korea’s best hope for giving its culture a genuinely global presence.” If so, the best of modern Korean culture, which itself has moved farther past powerlessness than ever, is yet to come.

(Dongdaemun Design Plaza photograph: Eugene Lim)

You can follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.