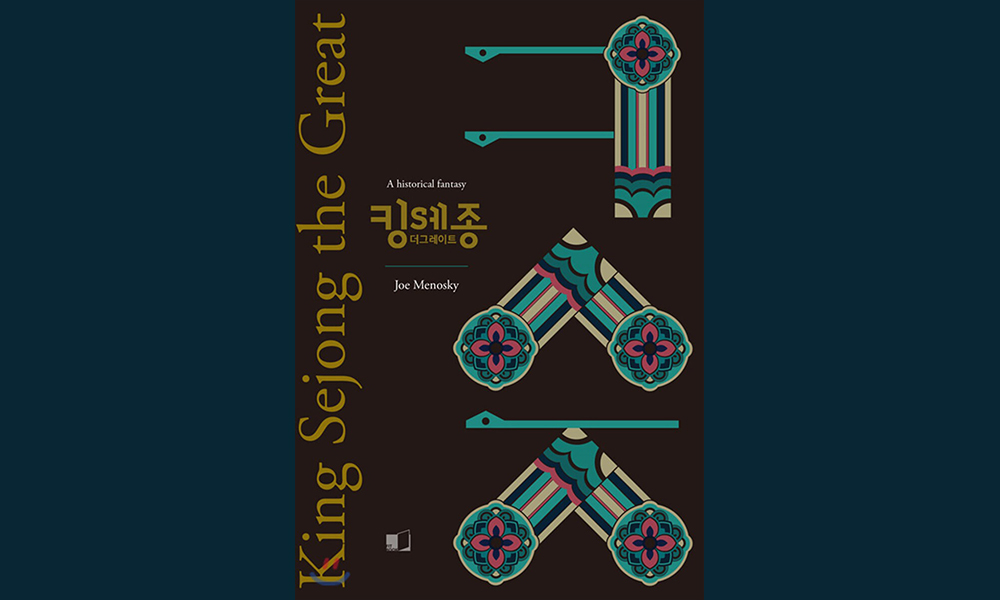

Apart from the pop music, television dramas, and movies that have made so many international fans in the 21st century, no aspect of Korean culture has fascinated Westerners as much as the Korean alphabet. In fact, if Westerners know only one thing about Korea, they tend to know that its language uses an alphabet, not a set of complex logographic characters of the kind seen in written Chinese and Japanese. If they know only two things about Korea, the second is often that this alphabet was invented by one man, a Korean king of centuries ago. This piques enough of a fascination in some Westerners to get them looking up who he was, when he lived, and what else he accomplished, knowledge that can inspire feelings of admiration. But only one such Westerner has been inspired enough to write a novel: Joe Menosky, author of King Sejong the Great.

Here the book was published in both English and Korean translation last October 9th: Hangeul Day, the holiday in honor of the Korean alphabet whose name literally means “Korean writing.” This as opposed to classical Chinese writing, which until the invention of hangul in the 1440s all Koreans used — or rather, all literate Koreans used, literacy having been limited to a small upper class consisting mainly of aristocratic scholars and government officials. History remembers King Sejong the Great (whom a Korean in a language-exchange group cautioned me years ago never to refer to as simply “King Sejong” in Korean, lest I give offense) as the quintessential benevolent monarch, overseer of a host of scientific, military, economic, and cultural advances of which hangul is the best-known and most enduring. For nearly all their reading and writing today, Koreans use an only slightly reduced version of the same alphabet Sejong invented.

Whether or not the king invented hangul by himself remains a matter of debate. Some sources describe him has having led a kind of committee to its creation, while others frame it as a practically individual accomplishment. In the novel’s prologue, Menosky writes that he deliberately opted to tell the latter version of the hangul story: surely the one with greater potential dramatic intensity, but also the one that would more closely have aligned with his own feelings about Sejong, which by his own admission approach “hero worship.” This alongside his disbelief that “this story was not universally known. If a European ruler had invented an alphabet for his or her people, everybody in the world would have heard about it.” Indeed, such an equivalent is difficult even to imagine: “Leonardo da Vinci as rule of Florence? Isaac Newton as the King of England?”

Korea has drawn many national heroes from the past millennium, and especially from the Joseon dynasty of 1392 to 1897. Not all of their heroic credentials have gone unquestioned, but however vague or contradictory the records of his time, King Sejong seems to have been the real deal — to use a modern expression, and one that finds its way into the text of King Sejong the Great. Rather than opting for any kind of medievally inflected narrative voice, Menosky makes full use of 21st-century English, often of a strikingly casual variety. “With its emphasis on reason over mysticism and reality over world-as-illusion,” he writes, the 15th-century state religion of neo-Confucianism had become “specifically identified with the Joseon dynasty ‘brand.'” Later he describes a Japanese pirate ship, its bilge “lit by one of the ballast weights — a heavy stone lamp that had been boosted from a Buddhist temple somewhere.”

An editor at an American publishing house would doubtless have sent those lines back, but the novel wasn’t published in the United States, and even its English edition comes from a small Korean outfit called Fitbook. There the manuscript seems not to have benefited from the kind of non-authorial attention that native English readers take for granted in long-form fiction: its nearly 400 pages are dogged by missing words, awkward line breaks, drifting tenses, sentence fragments, unfortunate repetitions, and even apparent typos. To some degree this must be a result of its unconventional path to publication. But as anyone who has paid much attention to English-language materials in Korea knows, while this society may obsess over English as a status language — occupying as it does something like the place of Chinese in the Joseon dynasty — scant attention remains for the quality and polish of actual English prose.

The publisher will have taken much greater care with the Korean edition of King Sejong the Great, a translation that entails a certain rearrangement of the book’s premises. “I wanted to retell the story of his alphabet myself, in English, for anybody who had not heard it,” Menosky writes in the foreword, “which pretty much meant anybody outside Korea.” Hence the embedded explanations: “Are we not or are we not a Confucian society,” asks Sejong’s ‘longtime advisor, “whose stability — indeed very existence — requires fidelity to proper relationships? Ruler to Subject; Father to Son; Husband to Wife; Elder to Younger; Friend to Friend?” Hence, as well, Sejong’s running a “15th-century Korean equivalent of a think-tank,” commissioning the construction of a water clock resembling “the 15th-century Korean equivalent of a Rube Goldberg contraption,” and thinking his way through “the 15th-century Korean equivalent of splitting the atom.”

That last analogy refers to the acts of intellectual synthesis that culminate in Sejong’s creation of hangul. Menosky dramatizes the realization of this long-dreamed Korean alphabet’s form with a scene that places the king, for some time ailing and sensing mortality’s approach, in a hot bath. “A look of ‘Eureka’ appeared on his face. The same expression Albert Einstein might have had upon deriving E=mc2.” Given the setting established and exclamation referenced, surely Archimedes would’ve made for a more suitable comparison. But the most memorable qualities of this sequence are visual: not just the steam from the water, but the elemental reverie that subsequently plays out in Sejong’s head. The novel also opens with such a vision, one of falling green leaves: “The bright sun behind the leaves refracts through the moisture beaded on their surfaces,” producing an effect “both gentle and dazzling. Like fragments of something sacred.”

And then “King Sejong — late 40s, face generous, handsome, and kind — opened his eyes.” Anyone familiar with the conventions of screenwriting will recognize language of this kind, and having spent his career so far as a television writer, Menosky must know those conventions better than most. His résumé includes no fewer than four different Star Trek series (as well as Seth MacFarlane’s Star Trek sendup The Orville), and it’s hardly a stretch to imagine a co-creator of that universe being drawn to an enlightened monarch’s efforts to advance his people in the face of both treachery at home and threats of invasion from abroad. In Menosky’s telling, Sejong’s worries include not only his own ill health, but increasingly burdensome demands by the suzerain in Beijing, the approach of Japanese pirates off the coast, and the newly reunited Mongol tribes’ ambition to retake most of northeast Asia.

Even Sejong’s closest advisor Choe Malli turns against him as soon as he hears of the king’s hitherto clandestine hangul project. As Choe publicly opposes the introduction of an alphabet for the uneducated commoner, his voice speaks “for all the aristocracy; all the bureaucracy: the voice of the Confucianists who dominated this government, this culture, even this century.” Seeing in hangul “the means to vomit every trivial thought into potentially permanent existence” at best and a catalyst for popular revolt at worst, he nevertheless takes comfort in “the certainty that a few frantic scribbles of ‘meet me in the kitchen’ and ‘did you hear about so-and-so?’ scrawled on the equivalent of toilet paper in comparison with the immeasurable extent of knowledge and culture captured by the ideographs of the Chinese writing system was like a candle held up to the blazing sun.”

This is an unfashionable attitude in the 2020s, one Choe is ultimately made to pay for holding in opposition to Sejong’s “shockingly contemporary ideals of meritocracy.” Menosky follows the king’s official presentation of hangul, “the Correct Sounds for the Instruction of the People,” with scenes of the palace help quickly taking it up and using it excitedly to pass notes to one another. Even Lady Hwang, Sejong’s most simpleminded consort, finds she can use it to express the animal noises and birdsong the king had been trying to teach her to imitate — a clever gesture on the author’s part toward the uncommon richness of onomatopoeia in written as well as spoken Korean. With these themes, and with the many scenes of tense action of sudden violence it includes, this story could probably play well today in the East or West as, say, a television miniseries.

And indeed, a television miniseries was the original intent: in interviews, Menosky has told of first writing King Sejong the Great as a four-hour teleplay. Then his Korean management company made the connection to Fitbook, who asked him to convert it into a novel — one that, at least in its English version, bears traces of Menosky’s métier. What few screenplays I’ve seen have all amounted to carefully engineered exchanges of dialogue connected by broad descriptions of images and their intended effects. Stretches of this book read similarly: “The moment the knife pierced its flesh was the same moment the golden filigreed ritual headdress was lowered on to the head of the King,” Menosky writes of preparations for a royal ceremony occurring simultaneously in different parts of the palace. “As if, synchronistically, symbolically, at this moment, in this world and the next, they were one and the same.”

In a later scene, the King locks eyes with the Queen after experiencing a hangul-related epiphany. “The look on her face of both question and answer made it seem as if she knew exactly what he had been fixated on a few seconds ago. As if they shared a single heart/mind.” That curious slashed compound, which appears throughout the text in both narration and dialogue, is a presumably a reference to the Korean maeum, which carries connotation of the concepts of both “heart” and “mind” as we know them in English. Every translator of Korean literature deals with such culturally deep-rooted terms differently, and as a reader I tend to prefer them left untranslated, explained only by their context. The same goes for the much more widely heard han, an ostensibly complex mixture of bitterness, regret, and frustration that Menosky calls “the heart/mind soul/sickness of the Korean people.”

King Sejong the Great‘s uneasy inhabitation of its medium results in at least one major missed opportunity: for a book written in tribute to hangul and aimed at a non-Korean readership, it doesn’t offer much of an opportunity to learn the alphabet. A work of fiction is not a textbook, granted, and the internet has made truer than ever Sejong’s pronouncement that a smart man can master his creation in a day and a stupid man in a week. But if Helen DeWitt could integrate lessons in the ancient Greek alphabet and Japanese syllabaries so naturally and effectively into The Last Samurai, a novel set in modern-day London, surely the same could be done with the story of hangul itself. But then, DeWitt’s project is as thoroughly textual as Menosky’s — composed at a coffee shop in view of the King Sejong statue in Seoul’s Gwanghwamun Plaza — is visual.

In fact, I remember King Sejong the Great as if it had actually been a television series: nonexistent shots replay in my head of the water clock’s mechanisms turning, the Mongol arrows flying, the king sneaking out for street food in commoner garb, those falling leaves resolving into hangul letters “cascading in monochromatic green down a computer screen.” This despite the fact that I’ve seen almost nothing of the Joseon dynasty-set dramas popular on Korean television, and of which Menosky describes himself as an avid viewer. In recent years these series have depicted Sejong with some frequency, as have films like The King’s Letters (나랏말싸미), which flopped in 2019 despite starring Song Kang-ho (Korea’s favorite actor even before Parasite). Korean viewers’ desire for the beloved king on screen hasn’t yet been sated — to say nothing of the heart/minds he may yet win abroad.

Related Korea Blog posts:

The Great Korean Plastic Surgery Novel: Frances Cha’s If I Had Your Face

The Agony and Ecstasy of Learning Korean, Expressed by Memes

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.