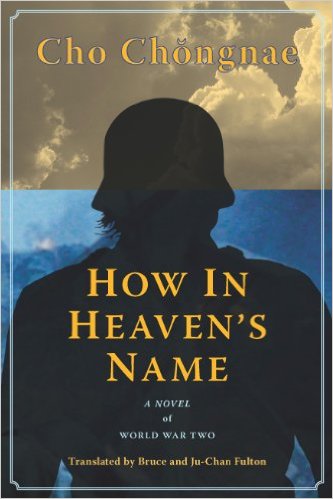

Korean translated literature very rarely features straightforward “war” stories, tending instead to focus on interpersonal and savagely political relationships against the backdrop of a war. This is true of World War II, The Korean War, and the Vietnamese War (many westerners are unfamiliar with Korea’s involvement in that “action”). When exceptions emerge, like the sprawling war story How in Heaven’s Name by Jo Jung-Rae (also romanized as Cho Chong-Rae, Cho Chongnae, and in other ways besides), they are worth noting. It is, like much of Jo’s work, based on reality — in this case, the story of Korean soldiers impressed into various armies — and mixes the brutal reality of war, the horror and uncertainty of capture, with the vagaries of post-war reality.

The novel provides both an excellent description of the nightmare life of the “grunt” in war – digging ditches in the evening, dying during the day — and is particularly good at catching the doomed feeling of soldiers, particularly those outmanned and outgunned ones who don’t really want to be there at all. Shin, the narrator, has been impressed as a Korean national into the Japanese army, which originally crushes the Mongolians against whom they are arrayed. But they soon face a much more formidable foe in the Soviet army, which leads to a procession of defeats and the continuation of Shin’s unlikely path.

Shin’s friends and acquaintances are picked off one-by-one, eventually leaving him as the sole survivor. He ends up serving in the Mongolian theater for the Japanese, the Russian theater for the Soviets, and the European theater for the Nazis, in whose service he is eventually captured by the Allies on D-Day. Along the way, almost unnoticed as the story goes on, he is forced to make one particular declaration that, while necessary for his survival, resounds down through all of his incredible experiences.

Jo’s writing here is direct and effective. As in most of his recently translated work, you do not necessarily read for his literary flourishes, but rather for his workmanlike stories examining interesting points in history. Also in the “as usual” category, the Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton do a good job of English translation. The pages fly by, and any reader interested in getting some more background will enjoy this Korea Society video of the Fultons discussing the book.

It should be noted that the “real” ending of this story, which seems to be based on an actual Korean soldier, is happier than that of the novel. In reality, “Shin” died of old age in New Jersey, though only after not being allowed to return to Korea because he served in the Soviet Army, which after the Korean Civil War marked him as a traitor. Sometime in the near future I’ll write more about Korean war fiction, or “war” fiction, but if you’re interested in a story that lives up to its incredulous title, especially one by as priceless an author as Jo Jong-nae, How in Heaven’s Name is well worth a look.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Finding Breezy Humor at the End of the World: the Stories of Kim Mi-wol

Sex, Surreality, and Social Conformity: Han Kang’s The Vegetarian

Charles Montgomery is an ex-resident of Seoul where he lived for seven years teaching in the English, Literature, and Translation Department at Dongguk University. You can read more from Charles Montgomery on translated Korean literature here, on Twitter @ktlit, or on Facebook.