Whenever someone has made progress studying a foreign language and asks which author they should try reading in that language, I always recommend the same one: Haruki Murakami. Though perhaps an obvious choice for students of Japanese, his mother tongue and the language in which he writes, his work has now made it into about fifty different languages in total. His stories’ globally appealing style, their abundance of non-Japanese cultural references, and their translation-ready prose style (legend has it he overcame an early bout of writer’s block by writing his first novel in what English he knew, then converting it back to Japanese) make them work just about as well in French, Polish, Turkish, Hebrew, or Mandarin as they do in the original.

When first reading novels in a foreign language, it helps to start with ones you already know from your own; undistracted by the plot, you can then focus exclusively on the mechanics of the words and sentences delivering it. Given Murakami’s enormous popularity (not to mention the evangelical nature of many of his readers) most enthusiasts of current fiction will already have read or at least encountered a few of his books. I first found my way into his work, as many do, through his first big bestseller Norwegian Wood, the vaguely autobiographical tale of a college student in 1960s Tokyo caught between two young ladies, one his dead best friend’s countryside sanatorium-committed ex-girlfriend, the other a lively and independent urbanite. From there I went on to read all of Murakami’s books available in English, then started over again with Tokio Blues — Norwegian Wood in Spanish.

During that re-reading of his oeuvre — or rather, obra — Murakami published a few more novels. The year before I moved from Los Angeles to Korea, I showed up at Skylight Books for the midnight release of Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage, his most recent. My girlfriend managed to snag the last signed copy they had, but I think the effort still establishes my own fan credentials. All of us around the world thrilled to the news that Murakami’s next novel, a “very strange story” called Killing Commendatore, will go on sale in Japan just a few weeks from now. Translations will surely follow over the next year or two, and the English one will bring that language’s Murakami book total up to twenty: fourteen novels, three short story collections, two non-fiction books, and a novella.

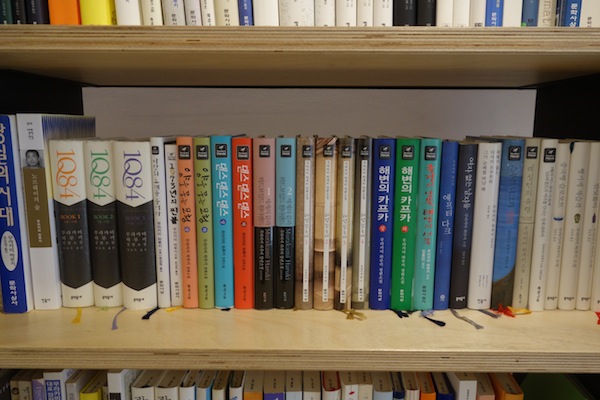

That number makes Murakami look decently prolific, or at least I thought it did until I came to Korea. The Korean language’s considerable grammatical similarity with Japanese (especially in comparison to, say, English) makes translation a much faster and smoother project than it is elsewhere, and so it stands to reason that Korea would get its Murakami books almost immediately after their publication in Japan. But not only does Korea get them sooner, it gets many, many more of them, and not just those still awaiting English translation, but those unlikely ever to be considered for translation into English or any other European language. I haven’t found an exact total, but Korean-language readers can already choose from, at the very least, three times as many Murakami books as English-language ones can.

Even as I write this I can see most of those books displayed right in front of me. They line the wall of Peter Cat, a Murakami-themed book café in the university neighborhood of Seoul where I live. (Murakami aficionados will recognize the name as borrowed from the Tokyo basement jazz bar, now elevated to mythic status, that he ran in the 1970s before turning full-time writer.) I stop in at least once a week to write, drink coffee, listen to the owner’s selections from his music library of Murakami-approved jazz, blues, and classical, and classic pop recordings, and above all read, sometimes bringing my own books, sometimes pulling off the shelf whichever volume of Murakami or Murakamiana strikes me as interesting.

Peter Cat has Korean editions of all of Murakami’s novels, all of which I recognize from having read them in English and Spanish. It also has Korean editions of all his short story collections, not all of which have yet appeared in English: his latest, Men Without Women (which takes its title from Ernest Hemingway’s book of the same form), has been out here for quite some time but won’t make it to the Anglosphere until May. It has the Korean edition of Underground, Murakami’s study of the Aum Shinrikyo’s 1995 Tokyo subway attack and its aftermath, but in the same two-volume form in which it originally appeared in Japan rather than the abridged single-volume form it took in English.

It also has Novelist as a Career (직업으로서의 소설가), Murakami’s reflections on the writing life, a work last I heard still on the desk of its English translator. No one could doubt that sufficient market exists for such a book in any country where Murakami has readers, and especially in those with large numbers aspiring to similar global-novelist status. He begins with his oft-told origin story — the unsatisfying university years, the early marriage, the jazz bar, the sudden rush of inspiration while watching a transplant American baseball player hit a double, the late nights writing by hand at the kitchen table, the sole manuscript mailed off to the literary magazine competition. Less well-known chapters of his professional life follow, ones in which, established as a name-brand author in his homeland, he makes the jump to New York and manages to wrangle himself several astute translators, a high-powered agent and editor, and a fruitful ongoing relationship with the New Yorker.

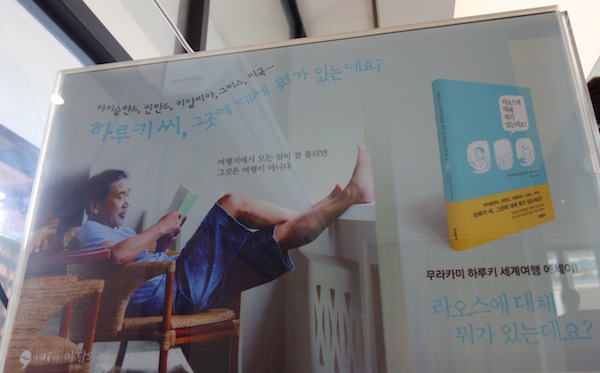

“Murakami Industries,” as the writer put it in a New York Times Magazine profile a few years ago, has always had an interest in cultivating and protecting his reputation in the West as carefully as possible. This has meant a consistent presentation as a capital-N Novelist, which has meant a de-emphasis, not to say suppression, of the less literary side of his work: travel books about countries like Greece, Turkey, Australia, Laos, Scotland, and Ireland (those last two toured specifically to pursue his interest in whisky), anthology after anthology of columns on various everyday subjects, and a collection of his recollections from the 1980s (on the likes of Reggie Jackson, “Eye of the Tiger,” the Marlboro Man, and the Walkman).

All of these have been published in Korean, as have the Portrait in Jazz books, Murakami’s meditations on icons like Chet Baker, Billie Holliday, Gerry Mulligan, and Ella Fitzgerald. You’d think that his writings on that most American of all musical traditions would interest American readers, but I’ve heard that Murakami doesn’t want to “tell them about their own music,” perhaps not realizing how few Americans know the first thing about their own music. The Korean market, even though it overflows with enthusiasm for his books — I don’t recall any book cafés in Los Angeles run in his honor, nor any churro shops named after his novels — seems to necessitate no such concern from him, nor, from what I’ve heard, has he ever made so much as an appearance in this country.

This neglect has, ironically, resulted in a huge abundance of reading material, albeit one sometimes made confusing by the tendency of the same material to come out under different titles and in different editions, translations, and collections. (Even Norwegian Wood underwent its first few printings as 상실의 시대, or The Age of Loss.) The unceasing flow of product from Murakami Industries here has led to the emergence of a robust field of Murakami studies. Peter Cat stocks plenty of the secondary literature, including analyses of Murakami’s novels by Japanese and Korean critics, glossy atlases of the places around the world significant in his life and work, guides to better living through his books, and even multiple volumes of recipes — pasta, cocktails, donuts and coffee, macaroni and cheese, hamburger steak — drawn from and inspired by them.

It seems Korean readers will tire of discussing Haruki, as they almost always refer to him, no sooner than they’ll tire of his work itself. In fact, I see that Peter Cat has just launched its own Haruki Book Club, a regular meeting in which to talk about and listen to the music referenced in a different Murakami novel each month. You’ll certainly find me there, provided I can get my Korean vocabulary up to a level that will allow me to meaningfully participate in time. At least I face no confusion about what books to study with.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Coffee Life in Korea

Why Korea Needs Alain de Botton (and Why Alain de Botton Needs Korea)

Korea, Where Book Podcasts Draw Standing-Room-Only Crowds

My Favorite Kind of Korean Podcast: the Book-Reading Show

You can read more of the Korea Blog here and follow Colin Marshall at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.