When first learning Korean in Los Angeles, I went to a Koreatown bookstore in search of simple reading material. There I picked up the first volume in a long-running a series of illustrated books for children called Happy World (행복한 세상). Its short, fable-like stories turned out to be united only by what struck me as an often thoroughgoing sadness, their titular world populated mainly by neglected children, impoverished students, downtrodden mothers and fathers, and crippled elders. “Oh, I know exactly what this means,” said a Korean friend to whom I showed the opening of one such tale, which simply introduced its young characters, a young brother and sister living in a mountain village with their maternal grandmother. “Their mother probably died in a factory accident, then their father drank himself to death, then the rest of the family was too ashamed to take them in…”

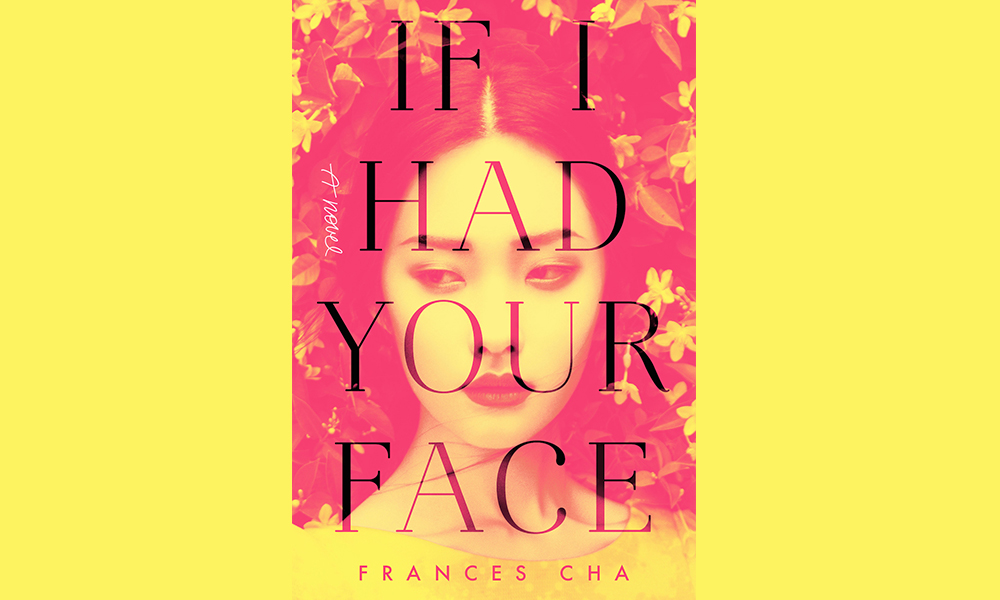

This implied history of misfortune could go on. Even then, film and literature in translation had already shown me that “every Korean story is a tragedy” — which, if not literally true, at times feels practically true. Observers of Korea thus often find themselves tempted to reference the concept of han, the deep-seated set of negative feelings defined as uniquely Korean. So do some Koreans: in Frances Cha’s new novel If I Had Your Face, one character remembers hearing that her grandmother “had choked to death on han — the pent-up rage from all the pillaged generations before her — seeing her parents die before her eyes, having served her mother-in-law as a body slave until she aged long before her time.” Though life has gone rather better for the speaker and the book’s other principals, all young women in 21st-century Seoul, theirs remains an unhappy world.

Narrative duty rotates between four of these women, all of whom live in the same humble apartment building, the gray “Color House.” Ara, rendered mute by incident whose nature Cha holds for the end of the book, spends her days working as a hairdresser and her nights obsessing over a pop singer. Kyuri, having undergone myriad cosmetic-surgery procedures (“the stitches on her double eyelids look naturally faint, while her nose is raised, her cheekbones tapered, and her entire jaw realigned and shaved into a slim v-line”), has worked her way up to employment at a “room salon” that pays her to drink with and fawn over big-spending male clients. Miho, she of the han-choked grandmother, is an artist not long returned from studying abroad in New York. Married and pregnant, the thirty-something Wonna observes the “girls” living on the floor above her with a mixture of concern and envy.

Cha makes only subtle distinctions between these four voices, all of which are given to sudden shifts of register. Ara begins the book with an unfortunate cliché, describing her roommate Sujin (from whom we never hear any narration) as “hell-bent” on becoming a room-salon girl. Later, riding a half-empty bus to her hometown, she observes that “most of the filial legions transited days ago to the provinces.” Miho describes Kyuri, her own roommate, as “painfully plastic,” not long after calling her imminent meeting of her rich boyfriend’s celebrity mother “a momentous occasion of epic implications.” Kyuri complains about a client ignoring her “as if he hadn’t fucked me over a chair two nights ago” as well as Miho’s “smug air of proactive martyrdom.” Recounting a visit to a therapist as an adolescent, Wonna remembers her own curiosity about “what sorcery elicited these precipitous prices.”

But in a plainer-spoken mood, Wonna also best evokes their building’s neighborhood, a run-down corner of the ostensibly glamorous Gangnam. “During the day ours is an ugly street,” she says, “washed out and dusty with trash piled up and cars honking and trying to park in odd corners, but at night, the bars light up brilliantly with neon signs and flashing televisions. In the summer, they set up blue plastic tables and stools outside and I can hear parts of people’s conversations as they drink.” This could describe a number of neighborhoods in Seoul, but the novel’s portrayal of the city hardly lacks specificity. Cha trusts the reader to know, or infer, what it means to work at the most expensive room-salon in Nonhyeon, to eat a croissant in a café on Garosugil, or to sit out on the steps “like characters in some musical on Daehakro.”

This alone would make me recommend the book, and it doesn’t stop at place names. Cha’s characters live in a shared “office-tel,” speak of the privileges of being “born into a chaebol family,” address older co-workers as “sunbae,” and claim that relatives need to be “exorcised by a mudang,” all without the explanations shoehorned into so much Korean literature on the assumption that readers know (or care to know) little about Korea. They’re seen “gaming furiously in a corner of the PC bang” and eating at a “favorite pocha, where the fish cakes in the fish cake soup are just the right marriage of chewy and salty.” That “fish cakes” doesn’t land quite right in a book whose foods are almost all, blessedly, romanized rather than explained, from tteokbokki and soondae to banchan, against whose unsuitable standard English rendering of “side dishes” I’ve long wanted to launch a one-man campaign.

Owing in part to this vocabulary, much of the dialogue sounds plausible enough to make me speculate on what the original lines would have been in Korean — a credit to Cha, since she wrote the book in English in the first place. If I Had Your Face is in a sense not a Korean novel, having originated in the resoundingly un-Korean setting of a Columbia MFA workshop. A Brooklyn resident most of the year, Cha seems to have a foot in each of the parallel social systems of American fiction defined a decade ago by n+1′s Chad Harbach as “MFA vs. NYC.” If indeed she is one of those writers who can “slip between these two cultures before winding up perfectly poised between them,” she can also draw from other cultures besides, having grown up in not just the United States and Korea but Hong Kong as well.

The novel evinces both familiarity with its Korean subject matter and understanding of what gets an English-language readership’s attention. Into its story Cha incorporates aspects of 21st-century South Korea the Western media have relied upon to inspire grimly admiring fascination: its social and economic pressures, its boy-band- and girl-group-dominated pop music, and especially its aggressive plastic surgery industry. Of the main characters, the room-salon girl Kyuri seems to have had the most work done (including something called “double jaw surgery”), an investment that has landed her at one of the establishments known for employing “the prettiest 10 percent of girls in the industry.” To the aspirant Sujin she offers contradictory counsel: “Look, I am not saying I regret having jaw surgery. It was the turning point of my life. And I’m not saying that it won’t change your life — in fact, it definitely will. But I still can’t say I recommend it.”

I admit that I don’t understand Korean plastic surgery much better than I did four years ago, when I first wrote about it here on the Korea Blog. Beyond me are even simple matters like what kind of eyelids people are supposed to want and why, though they certainly aren’t beyond Sujin, whose eyelids have been “done” since high school. Alas, high school was in Cheongju, a provincial town hardly known as a surgical mecca. “The doctor who performed the surgery was the husband of one of our teachers,” remembers Ara, also a Cheongju girl. “About half of our school got their eyes done there that year because the teacher offered us a 50 percent discount.” Evidently they got what they paid for: Sujin’s appearance betrays the fact that “the fold on her right eyelid has been stitched just a little too high, giving her a sly, slanted look.”

None of the narrators are Seoul-born, which is perhaps where their troubles began. Cha then compounds their disadvantages: Miho (and Sujin) grew up in an orphanage, while Ara spent her childhood and adolescence in the outbuilding of a wealthy household where her parents work as the help. Kyuri, from the also far-flung Jeonju, has a widowed mother who never taught her to cook (assuming she would live “a better life than a housewife daughter-in-law”) and who (under the impression her daughter is a marriageable secretary) asks questions like “What is the point of having a beautiful face if you don’t know how to use it?” Wonna, who until age eight lived with a wildly resentful grandmother, grew up to deliberately marry a man with no mother in order to avoid “the hate mothers-in-law harbor toward their daughters-in-law,” an emotion “built into the genes of all women in this country.”

Wonna dreams of her own daughter, her latest pregnancy after a series of miscarriages, turning out differently: “Unlike them and unlike me, you have a perpetual smile lurking at the corners of your mouth because you’ve had a happy childhood.” Whatever it has to do with happiness, all four characters have manifestly arrived at womanhood missing something essential. None of them come closer to wit than a kind of clenched sarcasm: “I’m not sure who’s worse, them or the men,” says Kyuri of the occasional female customers who pass superciliously through her room-salon. “Just kidding, the men are always worse.” But unlike in Cho Nam-joo’s Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982, another recent novel about what can go wrong for Korean women, multiple voices aren’t pressed into service of a single set of grievances, and in some chapters Cha even has them has one character deflate the pretensions of another.

Privately diagnosing Kyuri with “persecution mania,” Miho explains that she “sees herself as the victim — of men, of the room salon industry, of Korean society, of the government. She never questions her own judgment, or how she creates and wallows in these situations.” For her part, Kyuri (who’s considered going to New York herself, or to another foreign city with similarly low beauty standards where “people walk around with all kinds of ugly faces”) has her doubts about Miho’s impressions of America: “She probably didn’t understand much of what anyone said to her. I’ve heard her speak English before and it didn’t sound that fluent.” Yet in a reversal of the spoiled-student-abroad figure so common in Korean popular culture — and hardly without grounding in reality — Miho remains throughout most of the book its most appealing character, owing not least to her lack of interest in cosmetic surgery.

Invariably described by the press as “the naturally beautiful artist-in-residence,” Miho draws no small amount of attention with her un-retouched, only lightly made-up face and waist-length hair, an unusual combination on the streets of Gangnam. Often engrossed in her work of painting and sculpture, her approach to life throws into contrast Wonna’s bitter, self-regarding isolation, Ara’s addiction to the opiate of idol fandom, and Kyuri’s vulgar nihilism. “Why would you want to bring more children into this world so that they can suffer and be stressed their entire lives?” Kyuri asks, rhetorically. “And they’ll disappoint you and you will want to die. And you’ll be poor.” Miho responds by expressing her desire to have four kids. “That’s because you’re dating a rich boy, I want to say to her. But really, you should know that he’s never going to marry you.”

Miho met that “rich boy,” Hanbin, in New York, where — as in many a tale of Koreans abroad — she seems to have spent her time less among Americans than in a demimonde of her moneyed countrymen and countrywomen. (In the book’s funniest moment, a Korean party hosted at a lavish apartment erupts with delight when pizza comes delivered from Papa John’s, a middling American chain that has made a premium name for itself in Korea.) Hanbin was at first involved with Ruby, the New York gallerist who hired Miho and who feels borrowed from another genre, although as a glamorous femme fatale she ultimately proves deadly only to herself. After Ruby’s suicide, Miho resists the temptation to let Hanbin’s wealth and connections set her up in an artistic career for life, but he puts up less of a fight against the resculpted, voluptuized room-salon girls all around him.

Hanbin’s infidelity drives Miho to a television drama-worthy revenge fantasy involving requests for jewelry, demands that he buy out her exhibition, and leaks to “the women’s magazines — the thick bibles of paparazzi photos of the rich and famous — that he is my boyfriend. I will build myself up so high in such a short time that when he leaves me, I will become a lightning storm, a nuclear apocalypse.” By the novel’s end she has cut short her distinctive hair and said that “I might just dye it blue tomorrow. Electric blue.” Perhaps this is a kind of objective correlative of her lingering naïveté (suggested elsewhere by her comparative remarks on Korea and the U.S., as when she decries the status obsession of her homeland… as against New York City). But I suspect more than a few readers will react with a different sentiment: specifically, “You go, girl.”

America’s fiction readership slants female, and nothing about If I Had Your Face indicates that this is lost on the author. Nor, despite time spent in Asia, has she lost her grip on the trends in English-language literary fiction. This is the moment for novels that specialize in revealing the traumas of a character’s past and the reverberations of those traumas in the present. Cha executes these revelations — and skillfully — in not one but four lives. But she also stops short of flattering readers who “see themselves not as agents in life but as potential victims: of their dates, their roommates, their professors, of institutions and history in general,” as the New York Review of Books‘ Daniel Mendelsohn writes, grappling with Hanya Yanagihara’s acclaimed A Little Life. But nor will such readers, with their “preexisting view of the world as a site of victimization,” be much put off.

If I Had Your Face has received positive notices, if not quite the celebratory ones with which A Little Life met five years ago. “Taken together,” says Kirkus Reviews, “Cha’s empathetic portraits allow readers to see the impact of economic inequity, entrenched classism, and patriarchy on her hard-working characters’ lives” — a trio of abstractions that will date that line like a green shag carpet when the zeitgeist has drifted to other concerns. Higher praise would be to say, as indeed I would, that nothing in the novel feels untrue to the reality of Korea today, and that Cha never sensationalizes highly sensationalizable material (although at the intersection of K-pop and room salons, it would be difficult to outdo reality). What could she do with setting, character, and language, I eagerly wonder, if freed from the obligation to keep the right -isms and -archies in her crosshairs?

Related Korea Blog posts:

The Book of Jiyoung: An Explosively Controversial Korean Feminist Novel Comes Out in English

Ways of Seeing Korean Plastic Surgery

Factory Complex: How (But Not Why) Working Women Have it So Bad in Korea

Six Expatriate Writers Give Six Views of Seoul in a New Short-Fiction Anthology, A City of Han

French Nobel Laureate J.M.G. Le Clézio’s New Novel of Korea, and the Love of Korea That Inspired It

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.