The LARB Korea Blog is currently featuring selections from The Explorer’s History of Korean Fiction in Translation, Charles Montgomery’s book-in-progress that attempts to provide a concise history, and understanding, of Korean literature as represented in translation. You can find links to previous selections at the end of the post.

The question of a “postmodern” Korean fiction sits within the larger question of what postmodernism is. Descriptions of postmodernism tend to not be entirely definitional, but rather explanatory, often focusing on techniques. Some aspects of postmodernism include an inclusion of or reliance on inconsistency, paradox, fragmentation, parody, destabilization, solipsism, the rejection of meta-narrative, randomness, metafiction, pastiche, a mixing or blurring of low and high culture, an uncertain and internalized narrator, and more besides. In some of these ways, postmodernism it is similar to modernism, which also strove to overturn traditional methods of literature and express new feelings and ideologies — which certainly happened in a massive way during the colonial era, as Korea struggled to come to terms with modernity in general and colonization in particular.

But postmodernism, if one difference can be clearly drawn between postmodernism and its predecessor, is not concerned with fixing anything or making any kind of “constructive” criticisms. In fact, postmodernists often do not believe things can be fixed or improved, or perhaps even that a state of being fixed or a process of improvement exists. Instead, they portray a chaotic landscape, splintered by human subjectivities, sinking down under the inexorable gravity of inertia. The only responses to such a world are to bleakly accept it, in many cases becoming stoic or insane.

To define postmodern literature in this way can lead to era confusion, as some of these features have been present in Korean literature for nearly a century. The postmodern phase of Korean literature begins while other things are going on, and in fact, it might be fair to go back as far as Yi-Sang and Pak Tae-won, with their works The Wings and A Day in the Life of Kubo, the Novelist, respectively, in a consideration of original “postmodern” Korean fiction. Even after then, in 1980, Ch’oe Yun was writing in an extremely postmodern style in There a Petal Silently Falls and Yi Munyol was writing Twofold Song in fractured, fantastic, surreal one.

So what are we to make of the entry of postmodernism into Korean fiction? It was added to the recipe of Korean modern fiction, as it turns out, just as many things in the 20th and 21st century were: quickly, with strong outside influence, and typically hybridized with a Korean way of making sense of the world. As Korea considered the modern (read, perhaps, “foreign”) world, it looked for aspects of modernization it could understand and integrate relatively quickly. The process started early. But before diving into postmodernism as a specific era, it makes sense to revisit some of the predecessors, or genetic sources, of the Korean postmodernism we know today.

Yi Sang was a controversial figure even in his day, and the quickest look at his poetry suggests why.

At least one Korean critic derided his most famous work Wings, calling it “common as a straw hat in summer amongst works by new writers in Tokyo seven or eight years ago when new psychologism was at its height.” In fact, Choi attacks some of the very things that make Yi Sang postmodern, specifically the fact that in Wings, Yi quite consciously places his narrator in a airtight seal, removing him from any formal relationship to society or nation, and that there is no direct moral question (though commodification is certainly given a good raking over) raised in the story, nor is there a specifically national one. Finally, no answers or antidotes are suggested.

Yi describes Koreans as “townspeople like from those from a folktale,” and Yonsei Universty professor John Frankl notes that “in all cases, when referring to the people and things he observes, he scrupulously avoids the simultaneously totalizing and reductionist ‘we’ and ‘our’ which are otherwise so common in writing then and now. Such words would connect him — as a fellow Korean — to these people.” Yi quite explicitly separates himself from society, becoming one of the first Korean authors to make this postmodern move. Nothing about this rejection can be clearer than when Yi triples down on the rejection of the Bible: “I too become an apostle, not three but ten times over.”

“Black out the 19th century — if you can — from your consciousness,” Yi writes at the outset of Wings, immediately declaring his separation from history. As a statement of the narrator’s status, Yi says something similar: “Who’d guess that this room, split in two by a paper partition, is a symbol of my Karma?” This is Yi’s way of discussing his own position as outside of the reality of the times, and this separation is also seen in his characters. His struggle, or the struggle of his characters, is the postmodern one: he cannot reconcile what is in him with the “reality” he sees without. That Yi considered himself a writer, and person, of alienation is clear in some fairly apologetic words he wrote, just prior to his own death, to a friend: “When I look back on my past, I am full of regrets. I’ve tried to cheat myself. I thought I led my life in an honest way, but now I find it is nothing but an attempt to escape from reality. I’ll try to lead an honest life, fighting loneliness. At the moment this is my only concern.”

Kelly Walsh notes that Pak Tae-won was raised in the first “modern” era for Korea, that moment when it first underwent an urbanization that, similar to modern urbanizations, brought a steady stream of immigrants to the city. If culture shock is a necessary but not sufficient element of postmodernism, then Seoul of the 1930s experienced it in the Japanese occupation. As society, including in its very geographical layout of people and things, began to form new networks and relationships, many of which were far removed from traditional Confucian relationships of the pre-colonial period, Pak began writing about these changes and the issues they engendered.

Stylistically, Pak was a trailblazer applying the calm eye of a cultural anthropologist to the meticulous representation of urban, particularly street scenes. As the title of his representative work A Day in the Life of Kubo the Novelist suggests, in it he tells one day of Kubo’s life, recorded by order of events, in a modern stream-of-consciousness manner interspersed with formally similar forays into memory. As an added bonus, this story was also illustrated, and illustrated by none other than Yi Sang (although it is unclear if any editions in English include Yi’s art ). The story takes us on a tour of Seoul, traveling through Gwangwhamun, into bars, teahouses, and a train station, and even past a row of prostitutes. Kubo’s day ends on a little note of random happiness and the moral nature of this conclusion deviates from “pure” postmodernism, but the style is surely recognizable as early postmodernism.

The Poetry of John by Chang Yong-hak, an astonishingly modern work quite clearly influenced by French philosophy, was published in 1955. Attempting, among other things, to take in the effects of the Korean War, it uses a triple structure involving the parable of a rabbit trapped in a prismatically lit cave and the rabbit’s escape from it to an uncertain existence beyond, the life of the narrator Tong-ho as he moves from child, to soldier, to POW, to beyond the war, and the life — and death by suicide — of Nu-hye, Tong-ho’s dreamer friend.

Chang interweaves these stories skillfully through Tong-ho’s slightly uncertain perceptions, throwing in a rather large helping of existentialism as Tong-ho struggles with the meaning of life and experience, whether life itself is a betrayal of possibility, and the concluding equation that “living is sinning.” Along the way, Chang considers concepts including freedom, communism, capitalism, dehumanization, and violence, to name only a few, arriving at no fixed conclusions despite his protagonist’s search for answers. In the end there is no center, nothing to hold onto.

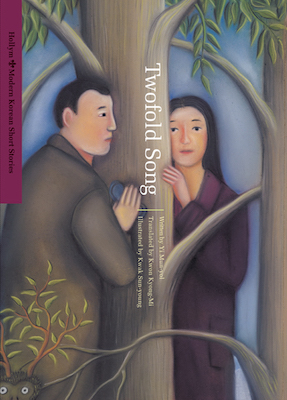

Yi Munyol’s Twofold Song begins as a man and woman come into being through conversation — or perhaps it is better to say, take human form through conversation. Perversely, when the conversation turns for the worse, the man and woman lose their forms: “Only then does her voice lose its sharpness. The blue cracks around her mouth gradually merge to form a wan smile. But the man has already changed back into a wet plaster statue. More than half of his right leg is buried deep in the ground because he inadvertently stretched it while talking.”

Later, we get our first glimpse behind the surreal curtain as to what the “reality” of the story might be when the man and the woman “build” a space to have sex, and commence to do so. At this point, surprising neither for a story by Yi nor for a story by any modern Korean, the issue of homeland surfaces. However, Yi quickly turns away from the typical Korean usage of the term as a return to, or reunification of, Korea itself. Instead, he has the man yearn for the “first” homeland, and during a sex act at that:

“I remember now… I’m a trilobite… a coral… a proliferan.”

“We’re taking shelter from the rain… in the hollow… trunk of an old oak tree. You, you feel… oh, so… warm.”

“I’m an elasmosaurus. I’m a dolphin… a tuna.”

At the climax, in perhaps the quickest cast of post-coital depression in literature, the tone of the conversation changes, turning again to regrets at having left the jungle. Once the sex act is concluded, the man and woman turn back from beings of flesh into beings of surreal imagination before parting. But Yi has one more surprise in store, as the next paragraph begins, jarringly, with a “just the facts, ma’am” description of an unknown character. That character, a bellboy at the hotel in which the man and woman had their final meeting, briefly describes how the preceding looked in his eyes: “Perverts… all that noise in broad daylight… at a time like this.”

Ch’oe Yun was a “Korean” national writer whose work was always dealt directly with the nation of Korea and its issues, albeit very modern ones. Her writing style, however was an early bridge between modernism and postmodernism, and for this she deserves to be considered one of the ancestors of Korean postmodernism. Ch’oe told her stories of Korea as stories of disembodied fantasy, or flat international narrative, even including characters overseas, not only rare choice in Korean literature but a controversial one. Her most famous work in translation, the three-story collection (or yŏnjak sosŏl, “linked novel”) There a Petal Silently Falls, reveals her range.

The book’s titular story was one of the first attempts in literature to confront the outrage of the Kwangju Massacre. The Kwangju Massacre, sometimes called the Kwangju Uprising by those not sympathetic to its aims, was one of the great South Korean atrocities of the democratization process. On 17 May 1980, martial law was declared by South Korean military leaders trying to quell a growing demand for democratization. The result was a short-lived stand-off that ended in a massacre followed by heavy censorship and the government denials the massacre had been committed.

The story examines a teenage girl’s descent into and occupation of madness after witnessing, and perhaps being partially responsible for, her mother’s murder. Told from the perspective of the girl, her abuser, and a group of college-student friends of the girl’s brother are attempting to find her, its multiple narrators dovetail with the often fractured language, imagery, and storytelling, particularly from the girl herself. The literary beauty of this work arises partly from the fact that, while it is clearly about the Kwangju Massacre, its non-specificity about where the atrocity occurred allows a reader to imagine it as a representation of any massacre. (This was likely also a politically astute strategy on Ch’oe’s part.)

In “The Thirteen Scent Flower,” a kind of postmodern fairytale, two young lovers named Bai and GreenHands nurture the “Winter Crysanthemum,” a new, beautiful, semi-narcotic, and potentially quite valuable flower. The flower is a result of their love, their dedication to handcraft, and partly their desire to flee society. As its fame grows, the same society that celebrates it naturally encroaches on the couple and their success, and the two find their brilliant creation threatened by extinction. Ch’oe masterfully mixes fairytale elements with descriptions of the “outside” world that deftly navigate space between parody and hard-edged description.

Yun also jokes about Korea’s often compulsive desire to create a “representative” example of everything:

“We can’t waste our time discussing again what we’ve already gone through the last time. How can we represent our country in an international exhibition without the Rose of Sharon?”

But the rose of Sharon isn’t a rare plant. We can’t violate the conditions of the exhibition from our very first participation.”

“But which is more important? ‘Representative,’ or ‘Rare’?”

“Representative,” surely.”

These proto-postmodernists paved the way for is an increasing number of postmodern or surreal works, all of which deal with Korean national problems while at the same time having direct relevance to the postmodern conditions of the world at large. While it may be one step too far to call them postmodernists, each of these authors has, in their time and their own style, adopted some of the technical stances of postmodernism as well as often adopting postmodern psychological themes.

So as we turn our attention to what might be called “modern” postmodernism, we should be aware that postmodernism was not merely a recently adopted trend in Korean literature, but rather a thread of Korean literature that has always intertwined with the larger, more national project, a strand that from the very beginning of Korean literature looked to tenets of uncertainty inherent in modernism and postmodernism to help explain a world that, at times, seemed entirely inexplicable.

Previous posts in this Korea Blog series:

Where Is Korean Translated Literature?

What Shaped Translated Korean Literature?

Why Does Korean Literature Use an Alphabet?

How Did Korea Get Fiction in the First Place?

Heroes, Fantasies, and Families: What Went Into the First Korean Novels?

Enlightenment Fiction and the Birth of the “Modern” Korean Novel

Literature Under the Japanese Occupation

Literature as Japanese Colonialism Fell

Deeper Into the War’s Aftermath, a Deeper Sense of Separation

The Social Tragedies of the “Economic Miracle”

Alienation, Politics, and Women

Charles Montgomery is an ex-resident of Seoul where he lived for seven years teaching in the English, Literature, and Translation Department at Dongguk University. You can read more from Charles Montgomery on translated Korean literature here, on Twitter @ktlit, or on Facebook.