No matter how much of an effort I make to explore Seoul, every so often something reminds me how much of the city I still haven’t discovered. That goes for the far-flung districts to which I haven’t yet made it as well as out-of-the-way parts of my own neighborhood, the same one I’ve lived in ever since moving here from Los Angeles. The first big hint of how much I might be missing out came when I happened upon a small bookstore not five minutes’ walk from my building, one nearly hidden on a quiet street running through part of an old neighborhood right next to one being scraped for a development of high-rises. Its storefront struck me as almost European, not least because of the dozens of empty wine bottles lined up on the ground outside. Even more intriguing was its name, written only on a sandwich board placed in the street: 퇴근길 책한잔, or “A Glass of Book on the Way Home.”

But one thing drew me in more than any other: the poster, taped up on the door, for Hong Sangsoo’s Right Now, Wrong Then (지금은 맞고 그때는 틀리다), a movie I wrote about here on the Korea Blog not long before discovering A Glass of Book on the Way Home. I’ve come up with few more reliable predictors of whether I’ll get along well with someone I meet here in Korea than whether they enjoy the films of Hong Sangsoo, which combine social comedy, formal experimentation, and a distinctive (usually budget-enforced) kind of rigor, with artistic results deeply rooted in both the culture of Korea and the culture of cinema itself. To get the biggest possible laughs at Hong Sangsoo’s movies requires a familiarity with Korea as well as resistance to taking the place too seriously; to fully appreciate them requires a sense of where cinema has been as well as a certain frustration with how timidly it has explored its possibilities thus far.

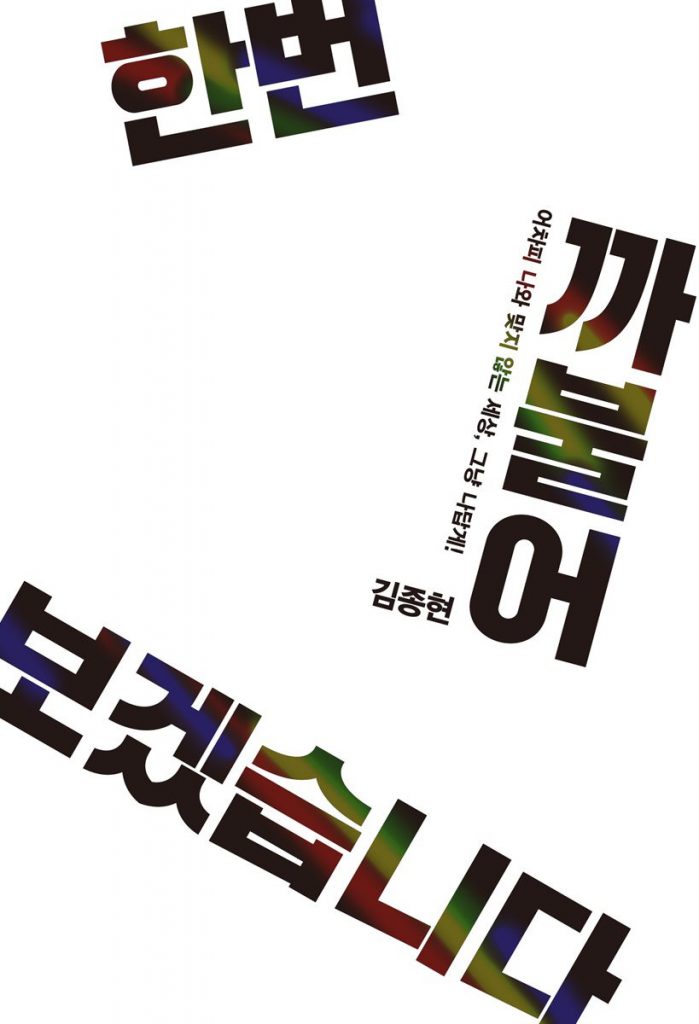

What Hong Sangsoo has done for Korean cinema, A Glass of Book on the Way Home’s proprietor Kim Jong-hyeon seems to have made it his mission to do for Korean life. Or rather, that has become a side-effect of his last few years of lifestyle choices, all of which might strike many of his countrymen as unthinkably radical: quitting a safe corporate job, couch-surfing through Europe, renting out a vacant former air-conditioner repair shop in an unfashionable area and turning it into a bookstore with no particular business plan. These and other decisions he explains in a new book called 한번 까불어 보겠습니다, which I might loosely translate as I’ll Goof Off for Once. In its 45 short essays, Kim lays out his philosophy of life as reflected by his thoughts on everything from travel (which he does by deliberately getting lost, a strategy whose employment he also recommends in daily life) to family (an entity that, in its controlling traditional Korean form, he rejects, though he does mention still living with his somewhat unconventional parents) to atheism and existentialism (“I am an existentialist,” he writes. “Don’t be scared”) to love and — in a chapter titled “I Like Sex” — sex.

He also tells the story of how and why he came to found A Glass of Book on the Way Home, how it first blew up on social media without his really trying to make it so, and how the experience has brought him into contact with others who question the restrictions and expectations of Korean life. As often in the case with these sentiments, many of the objections he raises to how things are apply to a much wider context than Korea, some to the entirety of the developed world; an increasing number of the conditions complained about in Korea are less specifically Korean than they may appear. But then, Kim wrote the book in Korean, for Koreans, and it’s no coincidence that, in my experience, everyone who shows up for the evening events he puts on at his shop is Korean but me. In conversations there I try to contribute “the Westerner’s perspective” whenever it seems at all relevant, but most of the time I’d rather hear what the other regulars have to say.

The first time I visited Korea, an American professor who has lived here for nearly 20 years told me of the common Western expatriate complaint about “meeting the same person over and over again.” I do understand where it comes from, but it certainly doesn’t apply to the people I meet at A Glass of Book on the Way Home. Judging by what he writes in his book, Kim himself may well have felt like he was meeting the same person over and over again before he turned bookstore owner — or rather, before he got the idea to use his bookstore into a gathering place. Trend pieces in America have long guessed at bookstores’ potential to survive by turning themselves into more broadly defined cultural spaces, but Kim has demonstrated how to do it with the absolute minimum outlay of capital and effort. One day, he writes, he got the idea to plug a portable projector into his laptop and use it to play videos onto his store’s wall. Why not hold screenings of his favorite movies and see who shows up?

For A Glass of Book on the Way Home’s first movie night, Kim chose The Green Ray by the French filmmaker Éric Rohmer. Though Rohmer was one of his own favorite directors, he writes — Kim’s times spent studying abroad in Francophone Belgium may have had some influence on that, not to mention Rohmer’s clear artistic similarity to Hong Sangsoo — he had no sense that many others in Korea even knew Rohmer’s name, let alone appreciated Rohmer’s work. But people did turn up, some out of existing interest, some out of simple curiosity, the screenings have continued on most every Friday evening since, and at some point someone even donated Kim an actual screen on which to project these movies. (Since then, Rohmer’s films have has also gained a bit of a profile in Korea, or at least enough of one that that twentysomething girls have started wearing La Collectionneuse shirts as mysteriously as they started carrying London Review of Books tote bags.)

Though a reasonably serious Rohmer enthusiast myself. I didn’t make it for The Green Ray, but I have seen at A Glass of Book on the Way Home the work of Michelangelo Antonioni, Jim Jarmusch, Jia Zhangke, and other respected auteurs of our time. Kim also tends to organize a field trip to a downtown theater whenever the increasingly prolific Hong Sangsoo puts out a new movie, often followed by a long eating and drinking session at one of the restaurants in which Hong has shot. I watched the results of the presidential election to replace the deposed Park Geun-hye there; more recently, I was there when Kim, impressed with Lee Chang-dong’s Haruki Murakami adaptation Burning, threw an impromptu gathering for us all to discuss it over drinks. Another night Kim’s interest in Charles Bukowski prompted him to screen Bent Hamer’s Factotum, and in I’ll Goof Off for Once he articulates the importance in his life of the epitaph on the poet’s gravestone: “Don’t try.”

That those two words have shown Kim a way forward might not add up to a Westerner: in America, at least, someone who ditched his career in his early thirties to start a new kind of bookshop might strike us as more ambitious than not. His admiring quotation of the line “Hell is other people” from Jean-Paul Sartre’s No Exit might seem similarly odd, but as Sartre himself later clarified, “if relations with someone else are twisted, vitiated, then that other person can only be hell,” because we can only “judge ourselves with the means other people have and have given us for judging ourselves.” That brings to mind any number of complaints I’ve heard Koreans make about Korean society and its tendency to make its members feel unfavorably compared to one another by a rigid, one-size-fits all metrics of success. (Whether that’s more or less grotesque than the sight of Americans clambering over each other for trophies of ersatz individuality is in the eye of the beholder, though I know which one I’d take.)

What Kim advocates in I’ll Goof Off for Once could be called ambitious unambitiousness, life lived without the drive to attain pre-determined goals but with even more vitality as a result. In the book he mentions his habit of thinking of death as often as possible in order to ensure a heightened awareness of his existence and how he uses it, and I, too — about year younger than Kim — have found the frequent memento mori increasingly necessary to the life well lived. In another essay he discusses his dreams of “living life like a firecracker,” referencing the examples of Romain Gary and Jean Seberg as well as Sid Vicious and Nancy Spungen. Perhaps that’s why he advocates lovers promising each other not that they’ll love each other forever, no matter what, but that they’ll love each other to the fullest each and every moment they happen to have together. A Glass of Book on the Way Home has already become a beloved space, but Kim has said elsewhere that he doesn’t want to run a bookstore for the rest of his life. Still, I hope he keeps this particular firecracker burning for quite a while longer — and, ideally, here in my neighborhood.

Image: A Glass of Book on the Way Home Twitter and Facebook pages

Related Korea Blog posts:

Travel Is Living: How Airbnb Ingeniously Markets to Korea

Why Do Koreans Love Herman Hesse’s Demian Above All Other Western Novels?

Korea, Where Book Podcasts Draw Standing-Room-Only Crowds

Korea Through the Eyes of Hong Sangsoo, the Éric Rohmer and/or Woody Allen of Korean Cinema

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.