Last weekend I took my first trip to Korea’s Jeju Island, a vacation spot popular enough to make the air route between it and Seoul the busiest in the world. But I wasn’t going on vacation, nor, strictly speaking, was I going to Jeju: my destination was Gapado, a much smaller island off Jeju’s south coast, the kind featured now and then on Travelogue Korea. There the conglomerate-owned credit issuer Hyundai Card, known for exclusive cultural facilities in Seoul like the Hyundai Card Music Library and the Hyundai Card Design Library, has spent the past eight years remodeling buildings throughout the island’s depopulated village. When an architectural magazine asked me to go have a look at the project’s results, I dug into the available promotional materials and found, among other things, Gapado-themed ASMR videos. This may surprise you more than it surprised me — or at least it may if you live anywhere other than South Korea.

Most in the English-speaking world have by now heard the term ASMR; some even know that it stands for “autonomous sensory meridian response.” Even among those of who’ve never watched a single ASMR video, many know that such productions involve whispering, brushing hair, tapping wood, crumpling plastic wrap, and other actions that generate the kinds of sounds ASMR enthusiasts find pleasurable. “Its triggers were as varied as watching someone fill out a form, listening to whispering sounds or seeing Bob Ross paint landscapes on TV,” The New York Times‘ Jamie Lauren Keiles writes of early discoveries of ASMR. The term itself was coined in 2010, displacing such less scientific-sounding also-rans as “brain-gasm.” Soon thereafter, deliberately ASMR-inducing videos exploded as a genre unto themselves on Youtube, where, Keiles writes, “legions of (mostly female) creators release, by my count, around 500 new videos each day.”

Though a notoriously trend-sensitive society, Korea developed its own ASMR scene later than much of the word did. Last year The Korea Herald‘s Choi Ji-won profiled the country’s acknowledged first “ASMRtist,” a young lady named Yu Min-jung, known on Youtube as Miniyu. “In 2013, Yu, who had longed to become an actor, was having a hard time after graduating with a degree totally unrelated to her initial goal,” writes Choi. It was then that she discovered the foreign world of ASMR on Youtube and began making her own contributions in Korean. Some ASMR videos use not just sound but actual language, or at least the kind of role-playing ASMR videos Yu makes — and that have subsequently succeeded here — certainly do. “From a late-night barber to a dermatologist, then from a scalp therapist to a caring friend removing makeup from a roommate’s face,” writes Choi, “Yu becomes a ‘healer’ for those craving sounds of comfort.”

In Miniyu ASMR’s most-seen videos, which have so far racked up more than 4.5 million views apiece, Yu simulates ear–cleaning, one of the genre’s most reliably stimulating activities. In the next three down, she engages in another ASMR standby, the eating of distinctively textured foods, like marshmallows and candied strawberries on a stick (available from street carts in certain parts of Seoul). This suggests a natural crossover with another specialized kind of video popular in Korea, indeed popular primarily in Korea and treated by foreign press as an untranslatable oddity: mukbang, whose creators and stars gain large viewerships by eating enormous quantities of food on camera. Last summer The Verge’s Dami Lee profiled Korean Youtuber Yammoo, who specializes in ASMR mukbang videos involving the consumption of “stones (made of chocolate) or light bulbs (made of candy),” and even “balls of air pollution (made of cotton candy).”

Wherever in they world they may live, fans of the now-developed Korean ASMR industry have their pick of creators to follow. Other well-known ASMRtists include Jiee, who in her biggest hit whispers while manipulating cosmetics; PPOMO, whose hourlong scalp massage from a couple years ago has now passed ten million views; Babzi, one of the rare male creators on the scene (and not surprisingly, one with a self-presentation not far removed from that of a K-pop boy-band member); and the distinctively named Pigsbum53, who in her top video pretends to get her viewer ready for a date. In Seoul magazine Robert Koehler mentions Dana ASMR, “one of the most popular Korean producers of ASMR videos on YouTube. Her “8 Triggers to Help you Sleep” has garnered over 6 million views and over 4,700 comments at the time of writing.” Other of her videos “share with audiences the ambient sounds of many of life’s experiences, be it eating, getting your ears cleaned or playing with multicolored slime.”

Koehler also addresses the seemingly disproportionate enthusiasm for ASMR here in Korea. “In a world where social media, the 24-hour news cycle, Netflix and thousands of cable channels keep us perpetually stressed and stimulated, people are growing ever more desperate for ways to unplug,” he writes. “A 2016 survey by the OECD revealed that Koreans sleep just seven hours and 41 minutes a day on average, the fewest hours in the organization. It’s unsurprising, then, that poll after poll reveals that an overwhelming majority of Korean workers either suffer from or have experienced burnout syndrome, a condition characterized by exhaustion, job alienation and reduced performance.” As a means of shutting off the flow of anxiety-inducing noise into one’s mind in hopes of loss of consciousness, listening to a 23-year-old girl apply skin-care products, eat fried chicken, or pretend be a barber is surely healthier than, say, binging on soju.

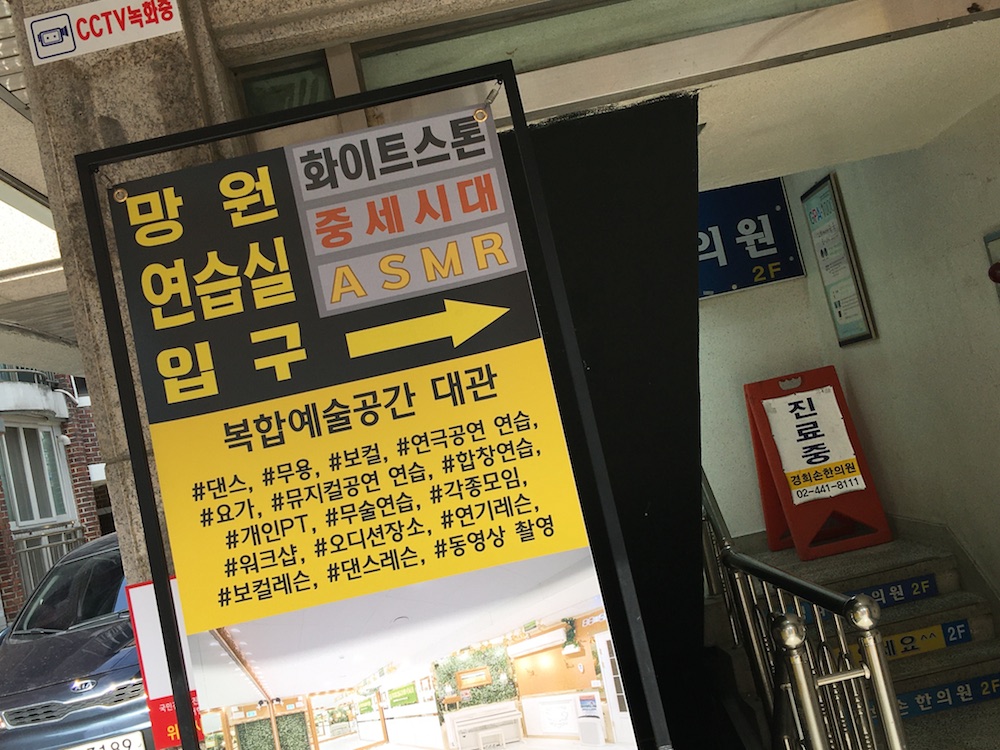

These examples hardly convey the full range of Korean ASMR offered as the 2020s begin. By now even Pengsoo, the irascible giant penguin whose face has gone from educational television to seemingly half the products now on sale in Korean convenience stores, is in on the ASMR act. (Having a giant body made out of fabric opens up a variety of sonic textural possibilities unavailable to the average human ASMRtist.) On the Youtube channel “ASMR soupe” you’ll find videos specifically engineered to create a relaxed mental environment conducive to studying; when a new location of a high-end bookstore chain opened in my neighborhood a few months ago, it commissioned “soupe” to create ASMR experiences for headphone stations installed around the premises. And as the governmental Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation’s K-Heritage TV proves, even the most venerable aspects of Korean culture are fair game for the ASMR treatment.

That channel has put up a whole playlist of ASMR offerings, all free of spoken words but rich in aural and visual detail, all shot in settings like a well-kept-up old courtyard house from dawn until dusk; kitchens during the making of traditional fall and wintertime sweets; a workshop where an artisan makes wooden fans the old-fashioned way; a Buddhist temple in Korea’s rural southwest; and even Jeju Island, a rich source of folk songs accompanied by the sound of local ceramics and stones. Hyundai Card has branded its low-key redevelopment of Gapado by drawing on the elements of the island’s traditional culture, from the green barley cultivated there to the female divers, called haenyeo, who since the 17th century have ventured out for shellfish to bring home to their villages. Its ASMR videos promote the place, whose name means “island of wind and waves,” by deriving pleasurable sounds from those very elements.

One could argue that the aesthetics of old Korea, the “land of the morning calm” where monks kindle fires and breezes rustle fields of barley, naturally gave rise to a culture that appreciates ASMR-like sensations. One could also argue that the unceasing educational, social, and professional demands of modern Korea created a population in desperate need of technologies to induce mental calm. “The internet is vast,” Keiles of The New York Times reminds us, “but it brings like minds together.” The labeling of ASMR marks “perhaps the first time the internet has revealed the existence of a new feeling.” And in Korea, the boundary between the internet and everyday life is porous in a way that still strikes Westerners as remarkable. But even before the internet as we know it, Koreans were relaxing to dubbed broadcasts of The Joy of Painting, hosted by the man they lovingly referred to as Bab Ajeossi (a bit like “Mister Bob” or “Uncle Bob”). Maybe in that respect, as in others, they were just a bit ahead of things.

Top image source: ASMR hyeady; bottom image source: K-Heritage TV

Related Korea Blog posts:

Travelogue Korea and the Dream of Isolation

Pengsoo, the Genderless, Shameless Giant-Penguin Antihero Winning Korean Hearts and Minds

Why Korea Needs Alain de Botton (And Why Alain de Botton Needs Korea)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.