Last week a voice boomed out of the speaker in my wall and told me not to go outside. One might more readily associate un-mutable commands broadcast directly into the home more with North Korea than South, but we live with them here in Seoul as well. Or at least many residents of apartment buildings above a certain size do, though through their speakers come piped not the national anthem or the stirring words of the country’s great leaders but information about renovation work on one floor or another, updates on the ever-shifting local garbage disposal policy, and announcements of impending visits from the gas-meter reader. Sometimes they also issue warnings about bad air days.

Other systems operate for the same purpose on a wider scale, such as the emergency alerts sent out to every mobile phone in the area when the measurements of the fine particulate matter floating around pass a certain threshold. The means of communication about this condition seem to strike many an observer as nearly as dystopian as the condition itself, though among expatriates talk about the air quality in Seoul has, in recent years, taken on an if-Bush-wins-I-swear-I’m-moving-to-Canada edge of obsessive frustration. Many Westerners here check the real-time air quality index daily or even more often; some post about it on social media, frequently and to the exclusion of almost everything else.

Why does Seoul’s air get so bad? For a time, the most often heard explanations by far simply blamed China. But the ever-increasing number of officially unhealthy days per year has prompted more rigorous analyses of the real causes, most recently in partnership with scientists from NASA. The research so far says that about half of the pollution inhaled in South Korea comes from sources in South Korea, be they cars and trucks, factories, or power plants (often coal). Seoul may have more days of healthy air per year than the likes of Beijing and Shanghai, but the country as a whole still comes in nearly at the bottom of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, air-quality rankings, above only Turkey.

Then again, it would: many of the OECD’s surveys have repeatedly ranked the country low enough to get official Korea — an anxious entity in the best of times — wondering whether the organization has assumed the mission of actively shaming it. And over the past few decades, the judgment of the rest of the world has taken on intense importance here, with one of the most forceful early pushes to pre-emptively placate it coming before the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul. Though last Monday marked a new record particulate-matter high since the current measurement system went into effect in 2015, it was by most accounts worse in the mid-1980s, when the government realized that its grimy air could spell a public-relations disaster and moved to relocate as much industry as possible out of the Seoul metropolitan area.

But then, Los Angeles had somehow pulled off its own acclaimed Olympic Games four years earlier, despite the worldwide infamy earned by its smog and the many queasily brown-tinted movies and television shows that smog produced. Environmental measures taken around that time provided many an Angeleno with their first or at least most vivid memory of a clear view across the city during the Olympics. Lee Shippey assessed the situation thus even in 1950’s The Los Angeles Book:

The great increase in industry has created a smog problem which makes Angelenos cry, figuratively and physically. Lying in a bowl between mountains and sea, L.A. has a climatic situation found only in a few places in the world. Fuel oil and gas create practically no smoke, but industry creates many fumes, and when there is no wind a heavier stratum of air above keeps fumes from traffic, industry, trash disposal or anything else from rising, and the mountains keep them from blowing away. Experts are working and millions are being spent to correct the situation but smog is still the city’s greatest irritation… often one cannot see the City Hall from six blocks away. Often there is a stinging mist which makes Angelenos rub their eyes and squint and swear — and makes photographers rival Niobe.

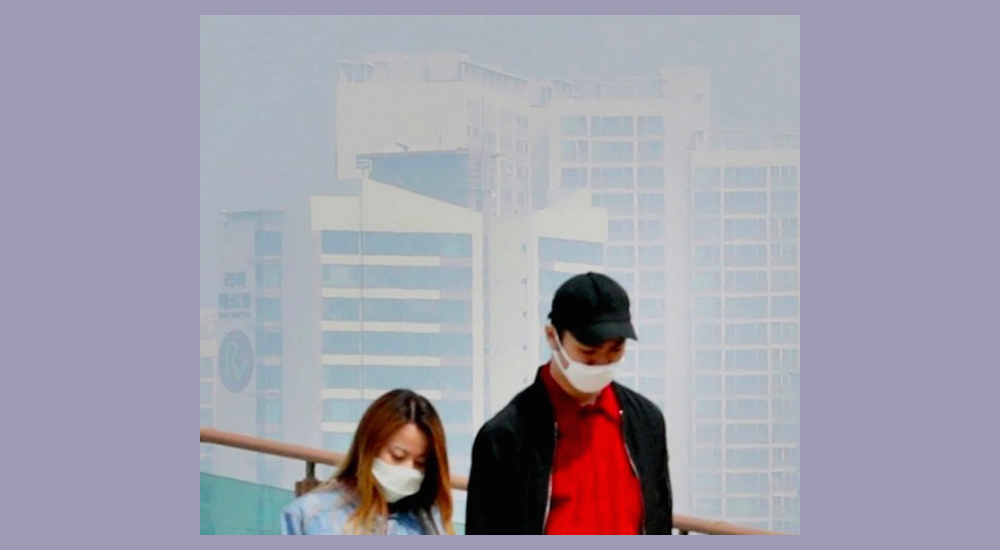

21st-century Seoul may have millions more photographers, broadly speaking, than did mid-20th-century Los Angeles, but rather than weeping, most of them seem to have taken to social media to post their most evocative shots of life in the haze: have a look, for instance, at the more than 500,000 pictures on Instagram tagged with the words mise meonji (미세 먼지), or “fine dust.” (The pictures in this post come from the accounts of Korean Instagrammers jy_lee_82 and 1bammarket.) On one particularly polluted day last week, a friend posted photographic evidence that Seoul Tower, usually clearly visible on its mountaintop in the center of the city, had vanished entirely.

An impressive commercial ingenuity has brought a large number of personal anti-particulate-matter devices to the Korean market relatively quickly, including personal and home air purifiers, sunglasses that promise to correct for what the stuff does to the light, and a variety of mouth coverings ranging from simple surgical masks to complicated devices with a somewhat more World War I aspect. (They also come in Hello Kitty designs for the kids.) Roughly one out of every 10 people out on the street has on a mask, in my observation, but I can’t say that I notice many fewer of them out and about in the first place. Life in Seoul does have a way of going on in good air, bad air, and worse air alike.

Some of that can, of course, seem fatalistic: I certainly don’t notice fewer people crammed into the designated smoking cubes, puffing defiantly away in proximity as close as a rush-hour subway car. Though some public and private fixes gave gone into effect at the margins — free public transit, artificial rain at baseball games — few Koreans profess an enthusiastic faith in the ability or willingness of their government, let alone China’s, to comprehensively address the problem. Then again, Angelenos probably felt the same way in the 1970s, and now Los Angeles, though it remains one of America’s most air-polluted cities, boasts about 300 more days of clean air per year than Seoul.

On that level, Seoul may have something to learn from Los Angeles. On most others, though, Los Angeles should be taking extensive notes on Seoul: its housing, its transit, its public restrooms. Just today I was singing the praises of those last to a Seoulite friend, by way of explanation of why the fine dust won’t drive me away any time soon. But she explained that, when she was growing up here in the 1970s and 80s, they were only a fraction as plentiful and — so she implied — the ones you could find, you certainly didn’t want to use. The prospect of Olympic embarrassment in the eyes of all the foreigners soon to arrive, however, changed everything. Maybe, then, all these expat complaints about the air aren’t quite as futile as I thought.

Related Korea Blog posts:

Living the Vertical Life in Seoul

Blade Runner 2049 and Los Angeles’ Korean Future

‘Bitter, Sweet, Seoul’: a Vivid Crowdsourced Portrait of an Unromanticized City

Why I Left Los Angeles for Seoul

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.